Guest post by Ghenet Besera & Milkie Vu.

Picture of Atlanta, our field site

Project Background and Context

The state of Georgia in the U.S. is a top destination for refugees in recent years. While refugee women are at risk for poor sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes and low SRH utilization, little research has examined factors influencing refugee women’s utilization of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. Our study is the first to use a theory-driven framework and community-engaged approach to investigate SRH among refugee women in Georgia and the Southeastern U.S.

We partnered with several community organizations and clinics serving refugee women in the metropolitan Atlanta area. Through our partners, we recruited refugee women and providers who cared for refugee women and invited them to participate in qualitative interviews. Additionally, our partners helped us identify and train interpreters to conduct interviews with women with low English proficiency.

Analyze (online) Interviews with MAXQDA

Step-by-Step Features Guide

Sample

Refugee women could participate if they were of reproductive age (15 to 49) and had origins from Burma, Bhutan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). We strived for equal numbers of refugee women from Burma, Bhutan, and the DRC. Within each group, we aimed to recruit adults (ages 18 to 49) and adolescents (ages 15 to 17), in order to better understand experiences with SRH across the life course.

Healthcare providers could participate if they provided SRH services to refugee women. We interviewed a total of 27 refugee women and 17 providers (e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, medical assistants). The providers practiced in different clinical settings, including non-profit medical clinics, private practices, community health centers, and hospital settings.

Data Collection Procedure

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with refugee women and providers. The interview guide was designed to elicit information reflecting the key domains of the Socioecological Framework and Penchansky and Thomas’ Theory of Access and perceptions and experiences regarding the following types of SRH services: contraceptive, HPV vaccination, cervical and breast cancer screening, and prenatal care. Interviews were audiotaped and lasted approximately 45 minutes long.

Data Analysis

We took notes during each interview and developed analytical memos after each interview. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional service. After audio recordings were transcribed, we imported transcripts and analytical memos into MAXQDA.

First, each of us independently reviewed four transcripts and their associated analytical memos. Using the initial transcripts, we generated codes using inductive and deductive approaches and thematic analysis. We then met and compared codes, refined definitions for codes, and created a codebook with agreed-upon definitions, examples, inclusion, and exclusion criteria.

We then recoded the initial transcripts with the new codebook. Additionally, we divided the remaining transcripts among the two of us and coded the remaining transcripts using the codebook. We connected codes to search for, develop, review, and define themes that emerged from the data.

Working with Memos video tutorial

Preliminary Findings

To date, we have finished analyzing interview data from the 17 providers.

The majority of providers were female (88%), White (53%), and originally from the United States (59%). On average, providers were 41.5 years old with 14 years of healthcare experience and 6.5 years of experience working with refugees.

Here we note several emerging themes from these transcripts: Providers discussed several patient-level barriers to SRH use for refugee women, including language barriers, a lack of transportation, and cultural beliefs regarding gender roles, modesty, family planning, and voicing healthcare needs. They also discussed clinic-level barriers such as funding constraints, limited SRH services offerings, time constraints, and a lack of interpreter and transportation services.

Additionally, providers mentioned how the diversity of refugee populations in metropolitan Atlanta made it challenging to fully address different communities’ healthcare needs, particularly with understanding cultural beliefs and offering interpreter services. Providers frequently discussed referrals to and collaborations with other clinics as a way to improve SRH service, but also noted several challenges associated with referral systems. Finally, providers offered strategies to promote SRH service utilization such as improving SRH service awareness, cultural humility, patient education, and service integration across systems.

Below, we provide two examples of the application of MAXQDA in our qualitative analysis. Note that clinic names have been redacted from the images.

MAXQDA Application: Code Intersection

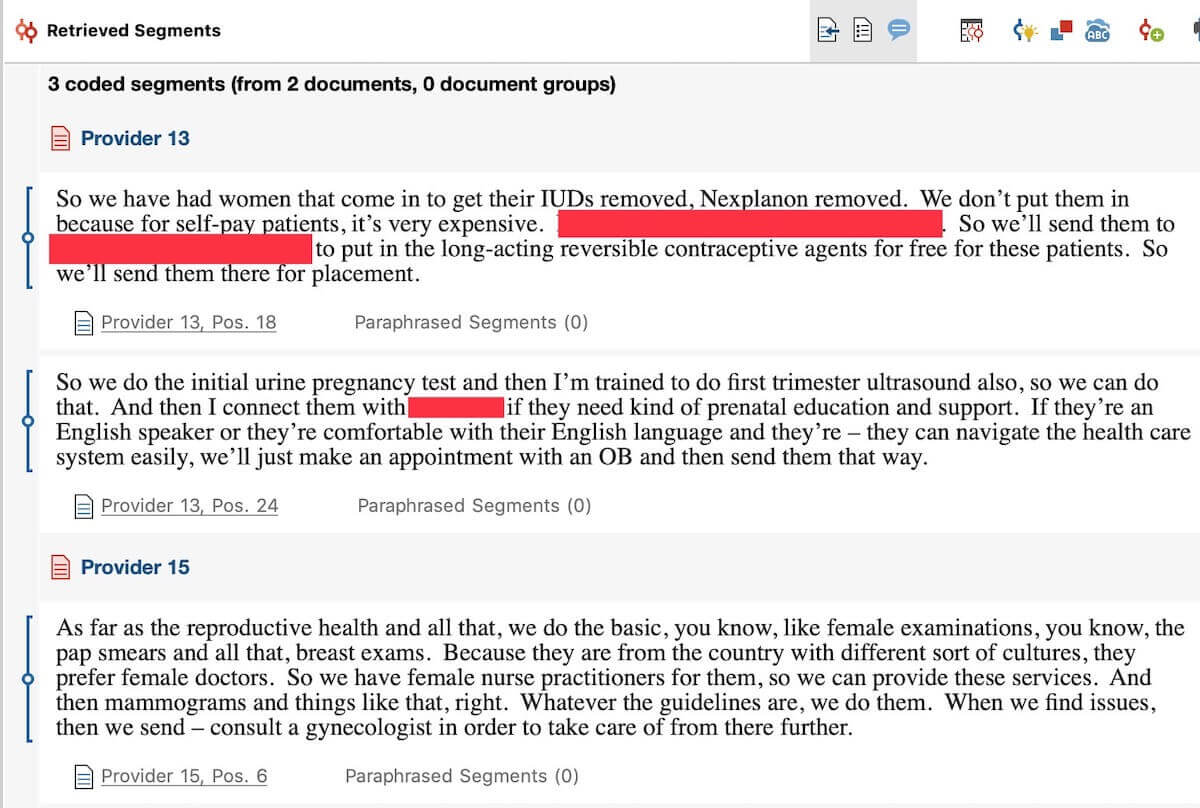

One emerging theme from our data is the providers’ use of referral services. Providers frequently discussed referring refugee women to other organizations or health systems to get services that were not available in their clinics. We were interested in exploring mentions of referral specifically for different types of SRH services. Thus, we used Complex Retrieval Functions within MAXQDA to explore intersections between referrals and SRH services.

Figure 1 demonstrates the intersections of discussion of referral systems and family planning services. Here we can see that the first provider discussed the lack of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods in their clinic. The same provider also mentioned several testings that their clinic could offer for pregnant women and another resource that women were referred to for prenatal education and support. The third provider discussed the available SRH services such as pap smears and breast exams in their clinic and brought up consulting with outside services (a gynecologist) if additional issues were found after screening.

Figure 1 – Visualization of the intersections of referral systems and family planning services using MAXQDA Complex Retrieval Functions

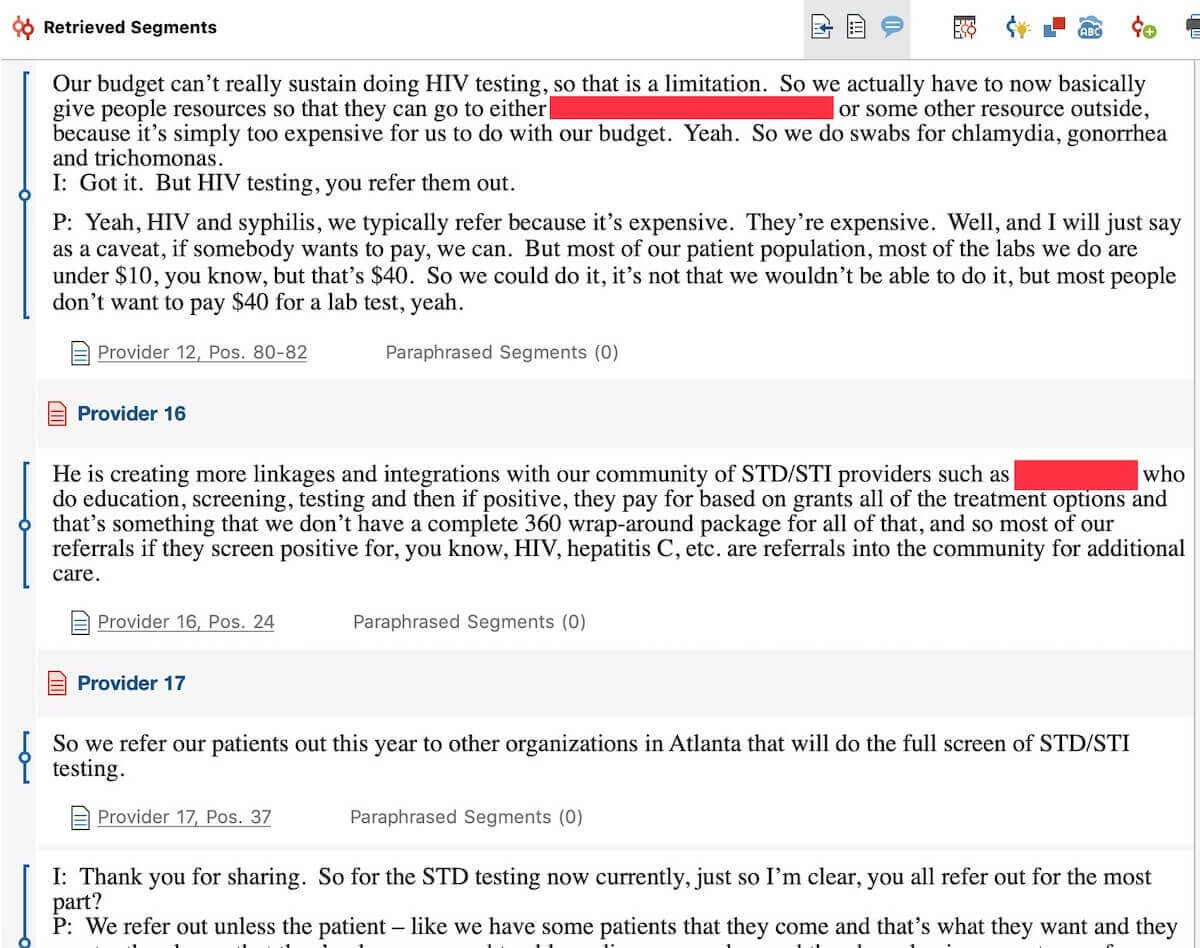

Figure 2 demonstrates the intersections of discussion of referral systems and testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STD). Through exploring data this way, we learn that the clinics were not really offering STD testing due to financial constraints on both their part and the clients’. Instead, they referred patients to several other organizations in Atlanta for HIV, syphilis, and Hepatitis C testing.

Figure 2 – Visualization of the intersections of referral systems and STD testing using MAXQDA Complex Retrieval Functions

Using MAXQDA to visualize the intersections of codes has helped us understand the capacity for SRH service offering for different clinics as well as circumstances in which they collaborated with other hospitals or organizations to provide different services to refugee women.

Teamwork with MAXQDA video tutorial

MAXQDA Application: Descriptive Statistics

At the beginning of the in-depth interviews with providers, we administered a brief survey to collect key demographic and background information (e.g., age, occupation/specialty, race/ethnicity) from participants. This information allows us to describe the participants in our study and contextualize findings. By using MAXQDA’s Variables functions and Stats feature, we were able to input the survey data and get descriptive statistics for our variables of interest.

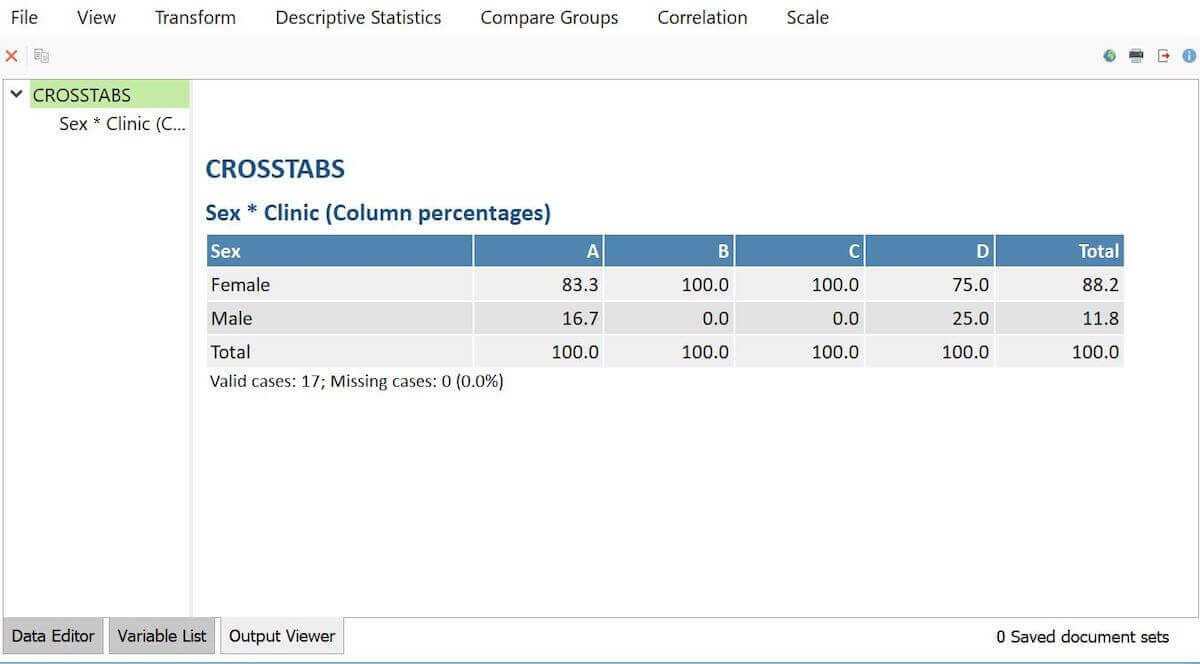

We first used the Variables function to input the specific variables and variable type. Then for each interview transcript, we added the data for the specific provider by using the Data Editor for Document Variables Function. Once we input our data, we used MAXQDA Stats to calculate measures of descriptive statistics of participants and compare participants on these key variables by using MAXQDA’s Crosstabs function. As illustrated in Figure 3, when comparing provider gender across clinics, we see that 88.2 percent of all participants identified as Female and 11.8 percent as male. Additionally, we can see how the proportion of female and male providers compare across clinics, with Clinic D having the greatest proportion of male providers.

Figure 3 – Visualization of provider gender by clinic using MAXQDA Stats

By using the Descriptive Statistics function within Stats, we also learned key descriptive information about our participants. Specifically, as shown in Figure 4, the average age of providers in our study is 41.5, the average years of experience in healthcare is 14 years, and the average length of time working with refugees is about 78 months or 6.5 years.

Figure 4 – Visualization of provider background characteristics using MAXQDA Stats

These functions within MAXQDA made data entry a seamless process and eliminated the need to use other software to store and analyze these quantitative data to provide context to our qualitative findings.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded through the Jones Program in Ethics Mini-Grant at Emory University, the Mini Grant Program from the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast (RISE) at Emory University, the Research Development Grant from the Organization for Research on Women and Communication, and the Healthcare Innovation Program at the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance (CTSA). The Georgia CTSA is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378.

About the Authors

Milkie Vu is a current PhD candidate in the Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. Previously, Milkie completed her Master’s degree in Social Sciences at the University of Chicago and her Bachelor’s degree in History & Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. Originally trained in cultural anthropology, Milkie has had a long history of conducting qualitative research in underserved minority communities, in particular with populations for whom English is a second language. Her research interests center on structural and socio-cultural determinants of health and well-being among immigrants, refugees, racial/ethnic minorities, and religious minorities, with an emphasis on cancer prevention and control.

Ghenet Besera is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Behavioral, Social, and Health Education Sciences at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. Ghenet has significant experience in leading and collaborating on sexual and reproductive health programming and research in various settings, including community and governmental organizations. Her research interests are in social and cultural determinants of sexual and reproductive health and the influences on sexual and reproductive decision-making and outcomes in both domestic and global settings. She graduated with her Master of Public Health degree from the George Washington University in 2013 and prior to that obtained her Bachelor of Science degree in Health Promotion and Education from the University of Cincinnati.