Guest Post by Dr. Orest Semotiuk, Department of Applied Linguistics, Technical University Lviv, Ukraine.

The Ukrainian-Russian armed conflict has two dimensions: the “physical” dimension (war as a phenomenon of political reality) and the “mental” dimension (a discursive construct). In the “physical” dimension, the conflict is localized (Crimea, ORDLO = occupied territories of Donezk und Luhansk region) in the “mental” dimension – globalized (with “national” and “international” levels).

To analyze the relationship between these “physical” and “mental” dimensions, we looked at political cartoons from the USA, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine and analyzed them using both qualitative (multimodal discourse analyses and frame analyses) and quantitative (computer-based content analyses with MAXQDA 2018) methods.

Why political cartoons?

“Decrypting a caricature is like interpreting a poem.”Dr. Orest Semotiuk

Our reasons for choosing to analyze political cartoons were twofold: Cartoons provide a format within political сommunication in which complex messages can be expressed through a single image; political cartoons criticize social deficits and shape specific images in the minds of their recipients.

Political cartoons are the subject of research in a number of disciplines – media and communication studies, media education, cultural studies, political science, linguistics, and literature. On the one hand, this diversity shows that the political caricature has significant research potential, and on the other, that it can be analyzed from various angles.

Corpus and methodology

I have been using MAXQDA since 2009 in my research on political communication and media texts. The master’s degree papers of my students were devoted to several different quantitative and qualitative aspect of political texts and media texts, also using MAXQDA (free trial version).

In this paper, we will present one part of our project and analyze the different visual and verbal means, which combine to create a cartoon’s effect. The research corpus consists of 535 political cartoons (from the USA, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine) published between 2014-2015.

The MAXQDA functions I found the most helpful for my methodological approach in this paper were as follows:

- Analysis > Compare Groups,

- Mixed Methods > Crosstab

- Visual Tools > Code Matrix Browser, Code Relation Browser & Code Map

Developing the code systems

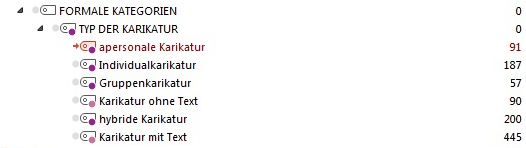

We developed two code systems in MAXQDA’s “Code System” window with formal and content related codes (Figure 1). The formal codes and subcodes were “cartoon type”, “cartoon with text”, “cartoon without text”, “individual cartoon”, “group cartoon”, “impersonal cartoon”, and “hybrid cartoon”.

Fig. 1: Our Project’s Code System (coded in German)

Each cartoon type explained

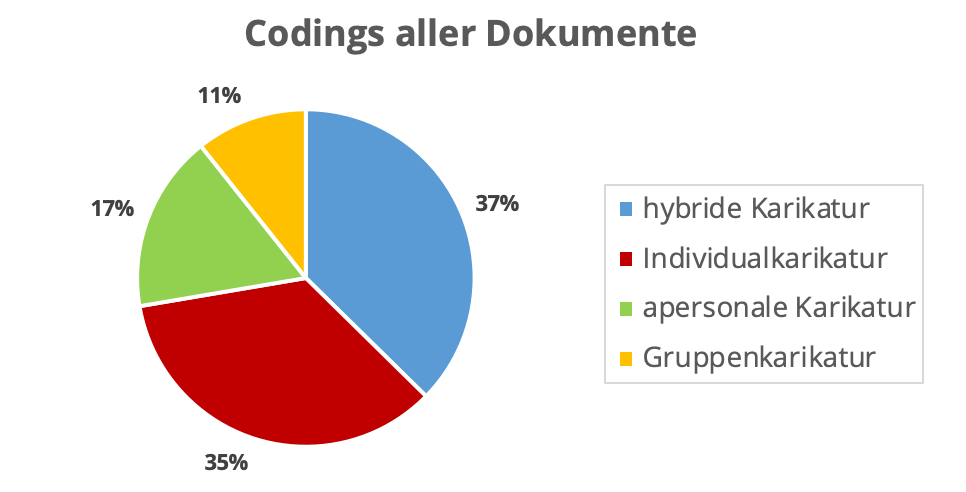

In our corpus, most of the cartoons include text. There were 445 “cartoons with text” of the 535 total cartoons analyzed. The most frequent types were the hybrid cartoon and individual cartoon (Figure 2).

- The “individual cartoons” depict the physical characteristics of politicians, while their gestures and facial expressions are related to a given situation. In this type of cartoon, the recognition value is high.

- The “group cartoons” depict states, people, social groups, institutions, and associations, stylized to an individual type. The features of the equipment lead back to the intended unity. Personalizations or easily recognizable symbols (national colors or heraldic animals) are often used here.

- The “impersonal cartoons” lack personal representations of individuals. In this type, instead, the problem is represented by means of effects and objects. These elements are then transferred from the viewer to concrete events or people.

- In the “hybrid cartoons”, the features of the previous types described are used in combination.

Fig. 2: “Coded Segments of all Documents” – Frequency of different cartoon’s types

(blue: hybrid cartoons, red: individual cartoons, green: impersonal cartoons, yellow: group cartoons)

Uses of humor: Description and quantification

The processes that take place in human perceptions of humor are stimulated by various techniques and these techniques usually work in combination with one another. The most popular techniques used in political cartoons are association, transposition, changing, contradiction, exaggeration, parody, satire, narrative, pun, disguise, and acquirement.

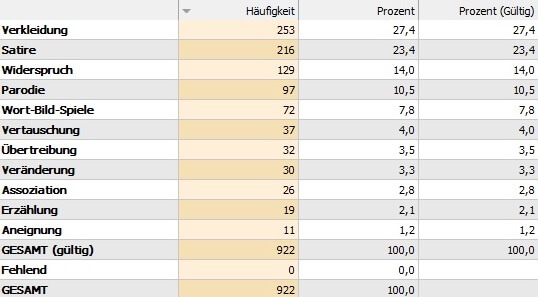

In our corpus, we have encountered all of these uses of humor, but the most frequently-identified techniques so far are disguise, satire, and contradiction (Figure 3).

Fig. 3: Frequency of different techniques in humor, shown using MAXQDA’s Code Frequencies function

(table columns from left to right: “Frequency”, “Percent, “Percent (valid)”)

Uses of humor: Examples of the most frequently used techniques

We’ll now provide some examples of the most frequent techniques and briefly explain them:

- Disguise: This technique uses symbols and metaphors. The “message” of the cartoon is implied rather than explicitly expressed.

- Satire: This technique includes ridicule, sharp wit, irony, sarcasm, and unmasks socio-political abuses.

- Contradiction: This technique is represented by the distortion of content and an emphasis on discrepancies.

Fig. 4: Bridgebuilders

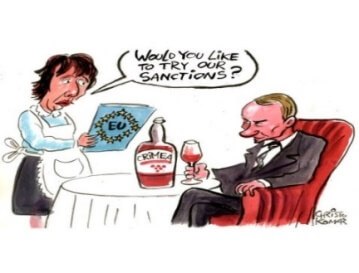

Fig. 5: Would you like our sanctions?

Fig. 6: Looking for those responsible

The boundaries between these techniques in the use of humor are very fluid. They usually overlap within a cartoon or appear in combination. It is important to note, however, to note that in every political cartoon at least one technique occurs. We also analyzed the occurrence of these techniques within different documents groups using the MAXQDA’s Compare Groups function in order to conduct both qualitative and quantitative analyses.

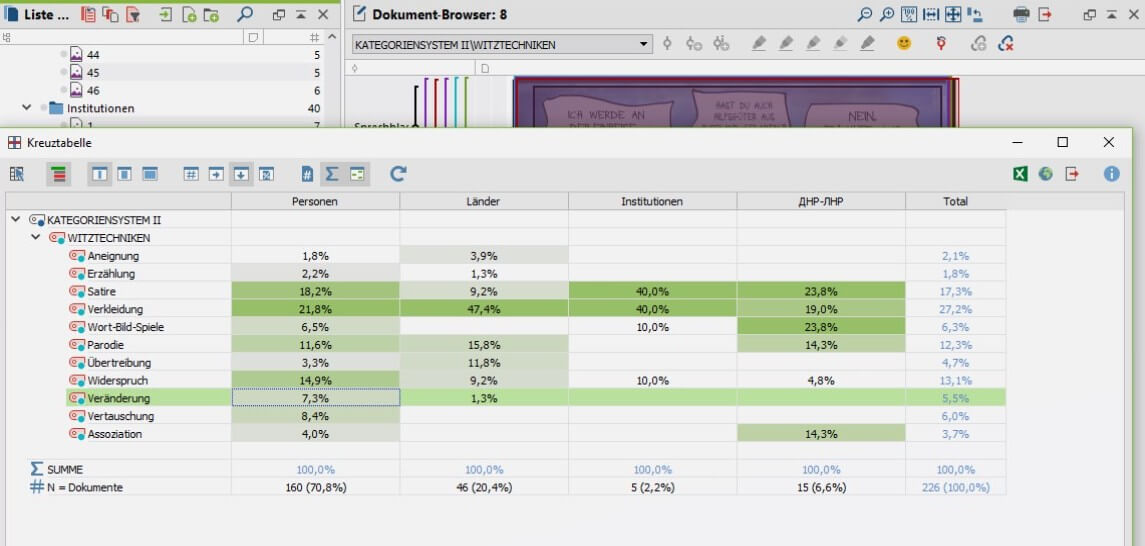

As we can see in Figure 7, the most frequent technique used in the document groups “People”, “Countries”, and “Institutions” is disguise (21.5%, 47.4%, & 40% respectively), in the document group «ДНР-ЛНР» satire and pun are the most frequently used techniques (23.8%).

After that, we used a qualitative approach and retrieved all the cartoons in the document groups, which used the technique of disguise most frequently. This approach helped us analyze all the symbols, metaphors and other means of implementing this technique (Figure 8).

Fig. 7: Techniques in the use of humor in document groups, shown using MAXQDA’s Crosstab function

Fig. 8: The “disguise” technique in document groups, shown using MAXQDA’s Interactive Quote Matrix

Author-recipient interactions: Levels and elements

Our next step was to analyze the verbal level of cartoons using MAXQDA. Interactions between a cartoon’s authors and their recipients take place on 4 different levels:

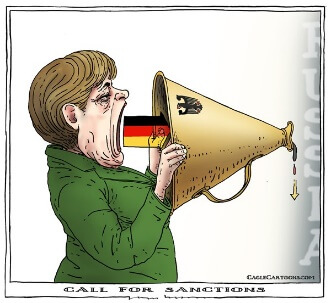

- Direct communication between the author and the recipient. On this level we have captions (subtitle or roofline – Figures 9, 10):

Fig. 9: Call for sanctions

Fig. 10: Normandy format

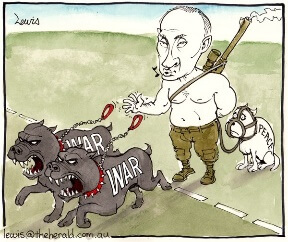

- Inserts (text in books/newspapers the characters are reading, inscriptions on buildings and objects, which provide institutional/spatial situating, text on posters and signs – Figures 11, 12)

Fig. 11: War

Fig. 12: I’ve lost my patience with him

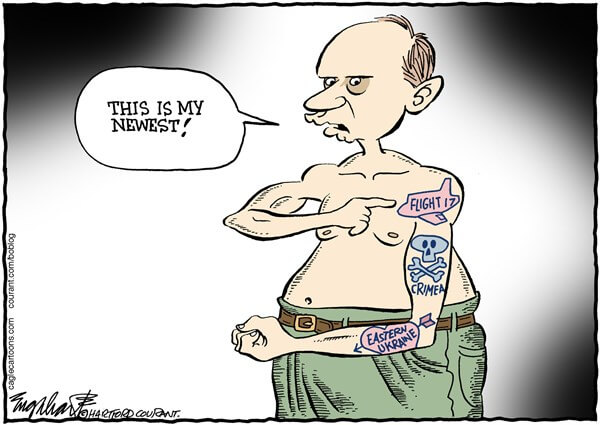

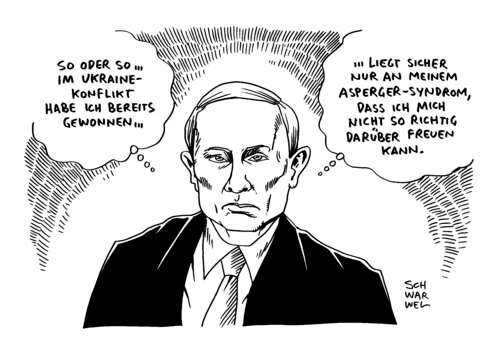

- Image-internal communication (speech bubbles: communication between the characters and thought bubbles: soliloquies – Figures 13, 14).

Fig. 13: This is my newest!

Fig. 14: Asperger’s syndrome

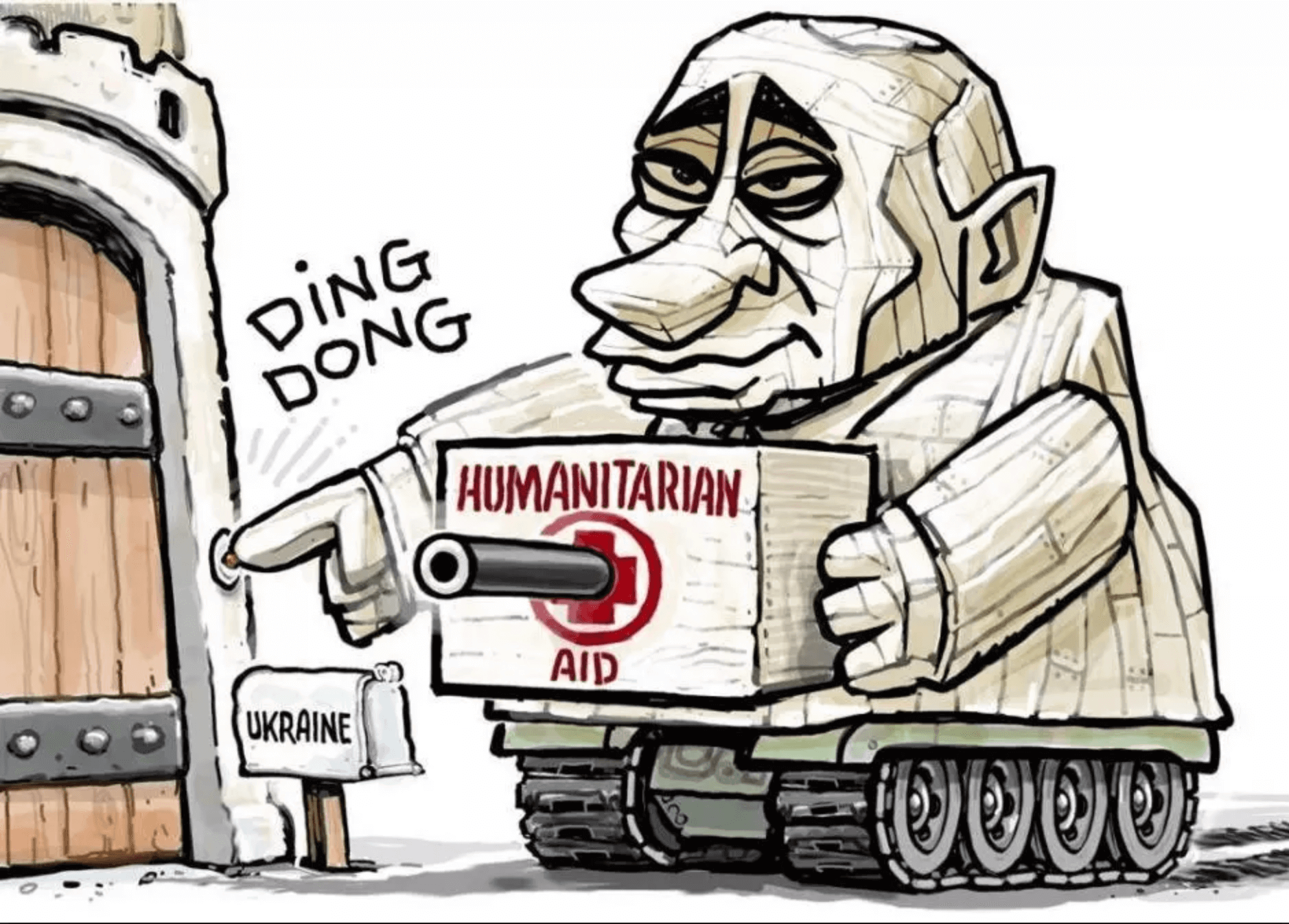

- Soundwords (Figure 15)

Fig.15: Ding-Dong

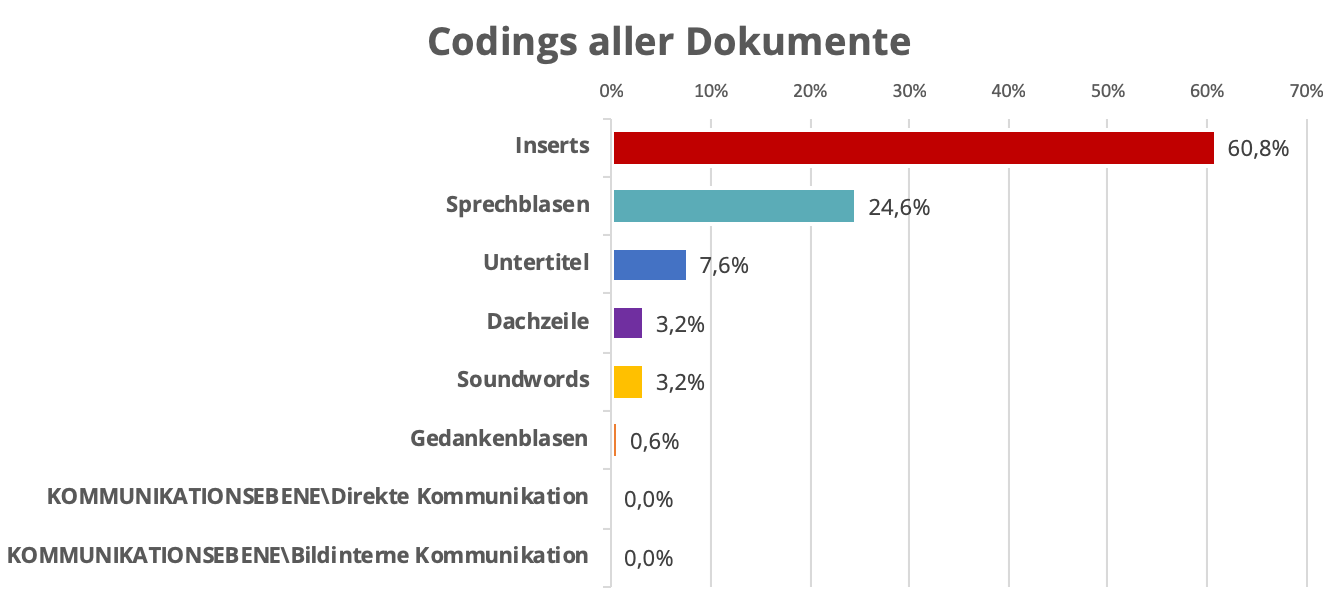

Here we discovered that the most frequent levels of communication between authors and recipients in our corpus were inserts (60.8%) and image-internal communication (speech bubbles, 24.6%) (Figures 13, 14).

Fig. 16: “Coded Segments of all Documents” – Frequency of verbal elements in cartoons

(red: inserts, teal: speech bubbles, blue: subtitles, purple: roofline, yellow: soundwords, orange: thought bubbles)

Conclusions

- Decrypting a caricature is like interpreting a poem. Both caricatures and poems point to a reality outside the irrespective art form. The meaning of a caricature does not open itself up to us directly, but only to the extent that we succeed in establishing relations between it and the political-social reality.

- The essential characteristics of a political cartoon, which are recognized as transdisciplinary, include: topicality, critical attitude, partiality, alienation, humor, and satire, as well as the combination of verbal (text) and nonverbal (image) components.

- For the typology of political cartoons, content-related and formal criteria, as well as the criterion “relationship between text and image”, are used.

- The techniques in the use of humor in political cartoons are based on different comedic theories and do not appear individually but in combination with each other.

- The analysis of political cartoons demands the combined use of qualitative and quantitative methods. This ensures objective and reliable research results.

MAXQDA greatly facilitates the analytical work of the researcher, in particular, quantification and visualization of the results. The advantage is that MAXQDA helps the researcher quickly and easily analyze images, e.g visual texts, which are, as shown above, important for political communication.

About the Author

Dr. Orest Semotiuk is an Associate Professor at the Department of Applied Linguistics, Lviv Polytechnic National University in Ukraine. His main research interest covers media linguistics and political linguistics, especially mediatization of armed conflicts in media texts and political cartoons. He works with verbal and visual texts applying quantitative and qualitative methods using MAXQDA.

Dr. Orest Semotiuk is an Associate Professor at the Department of Applied Linguistics, Lviv Polytechnic National University in Ukraine. His main research interest covers media linguistics and political linguistics, especially mediatization of armed conflicts in media texts and political cartoons. He works with verbal and visual texts applying quantitative and qualitative methods using MAXQDA.

Dr. Orest Semotiuk is an Associate Professor at the Department of Applied Linguistics, Lviv Polytechnic National University in Ukraine. His main research interest covers media linguistics and political linguistics, especially mediatization of armed conflicts in media texts and political cartoons. He works with verbal and visual texts applying quantitative and qualitative methods using MAXQDA.