This is a guest article written by Alexei Krivolap, an associate professor at the Department of Finance & Economics, Polatsk State University.

The concept “identity” has many faces and aspects in current society. In Cultural Studies disciplines, identity isn’t the easiest subject to research or discuss. Many social science theories assume to explain how identity actually works, but theory needs to be tested empirically, and gathering/analyzing identity-related fieldwork can pose challenges.

There is also a wide range of analytical work addressing issues around identity that considers the concept’s basis to be ethnic and religious (and other valuable orientations). But all of these current works to some extent have lost the concept’s universal character in order to explain what is happening in society today. This article will discuss my identity-focused research and how MAXQDA’s tools can help solve some, often painful, issues and unexpected challenges when conducting identity fieldwork.

Symbolic city gate in Minsk

Local Context: what does it mean to be Belarusian?

People in post-Soviet countries were faced with new challenges and threats after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is possible that one of the ways of solving some of these existing problems would be to create the concept of cultural identity. My research seeks to do so in the context of modern Belarus, a highly relevant example of a society impacted by the social and cultural situation in the former Soviet Union.

A quarter-century after the disappearance of the USSR from the world’s political map, its presence in the social and cultural sphere of the former Soviet republics can still be felt. The role and impact of new media in general, and the internet in particular, on the formation of cultural identity and this media’s place in national and cultural projects, is a topic with increasing importance recognized by a growing number of researchers.

Specifically, the creative industry also now has a large impact on the transformation of everyday life and culture in Belarus. Many new, interesting, and impressive ideas for projects in the information economy are emerging in the post-Soviet region. Some local startups have even been acquired by big corporations. And in other words, the creative industry plays a crucial role in transformations happening in Belarusian cultural identity on a daily basis.

Kastrychnitskaya street in Minsk is a place where creative industries meet the Soviet past face to face

But how do we study the impact of the creative industry on cultural identity? There are no direct connections between them to be seen and no economic statistics available for our case. This is why I decided to go into the field to meet people in the industry to pick up information from the ground up.

The research question is, therefore:

By proposing a new everyday lifestyle, how do creative industries thereby also create a new form of cultural identity?

Data Collection Strategy: a Grounded Theory approach

One of the main shifts in the understanding of what cultural identity is comes from Stuart Hall’s “Cultural Identity and Diaspora” (1990) and his idea of “social becoming” as a process of construction of cultural identity day by day. This idea explains that it is not possible to simply buy or adopt an existing cultural identity for yourself. Instead, long-term and practically endless creative work on the new form of cultural identity is needed. That said, examples of creative industries all over the world show us that their work can be a trigger for essential changes in cultural identity at the city- or even the national level.

My research seeks to understand the self-narrative of the new creative class in Belarus and how they self-identify. To do so, I needed to find local experts and active players in the Belarusian creative industry and conduct semi-structured interviews. This data gathering method allowed me to stimulate the discussion and note possible follow-up questions. I collected interviews with 30 experts in different types of companies in the Belarusian creative industry sector using a snowball sampling method. The summarized duration of the interview was 1,478 minutes with roughly one-minute timestamps in the transcript. Yes, it was quite the busy summer for me this year.

The semi-structured interviews were captured by a digital voice recorder and then analyzed in MAXQDA using a Grounded Theory framework. Grounded Theory postulates the development of theories from the bottom-up, where theory emerges from the data itself. The results of my research can be seen as an interpretation of logic to explain the development of cultural identity in terms of the process of social becoming.

Grounded Theory Analysis with MAXQDA

Analysis methodologies

The Grounded Theory framework I used consisted of three types of coding: 1) open, 2) axial, and 3) selective. The process of open coding allowed me not only create a new system of codes from my data while also leaving room for new ideas, which need I kept track of using memos in MAXQDA.

- Open coding allows for the splitting of individual respondent narratives into small pieces, or ‘subcodes’.

- Axial coding is the step in which to reconnect those separated fragments in a new way, establishing first links between categories.

- Selective coding means the accumulation and creation of the main categories and several sub-categories, from which a new theory can be founded and grounded.

For me, the most inspiring thing about conducting Grounded Theory research is the opportunity to hear the voice of an entire social group by combining the individual voices of different people. While open coding deconstructs narratives and separate points of view, axial coding gives me the opportunity to unite the single voices back into one common (theoretically-focused) narrative.

People can speak different languages, work in the different parts of the broad creative industries sector, (non)identify themselves as a member of the change-makers community, etc., but they all have practical experience in their field and thus social activism can, in a practical sense, be studied as a common vision of the future. It is, therefore, possible for each individual to feel what it is like to have been a part of creating the whole narrative of the “creative class” in their country. For now, my interview participants do not identify themselves as a social group, but in my view, to survive and succeed, they will need to do it soon. Any attempt to study the cultural identity must be a probe to guess something about the future not simply the study of national identities today compared to the past.

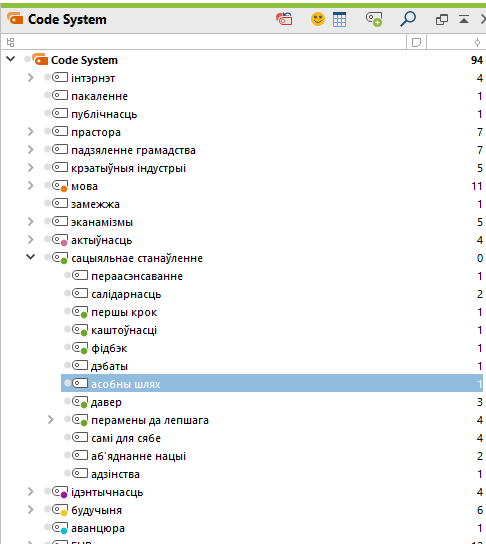

Figure 1: Trees of transcribed texts in MAXQDA

Common Problems in Identity Research and How to Solve Them

Problem #1: respondent accessibility

One of the biggest problems in qualitative research, in general, is the issue of how to access informants. There exists no specific power in the world to push other (and often very busy) people to take the time to talk to the researcher. For researchers who cannot afford to financially compensate their informants, participation is usually only based on goodwill – it is never an obligation. After multiple formal rejections by email or phone, the researcher can give up and forget about a certain potential expert or try to find an acceptable alternative.

An example of such a replacement could be a secondary interview strategy where data is collected from interviews that were published in the media and are then analyzed as a secondary source. It is absolutely clear that these secondary interviews cannot be used on par with primary ones (where the researcher conducts the interview themselves), but secondary interviews may be useful for a better understanding of the general context. MAXQDA allows the researcher to quickly and easily separate such collected secondary text and self-collected empirical interviews. To do so, you can create separate document groups in MAXQDA’s “Document System” window for different types of interviews.

If I had had no chance to meet the person for an interview for whatever reason, I was often able to find a published interview in the media. I didn’t count the secondary interviews as my own because I just gathered them from other open sources and currently, I have 4 secondary interviews from the media and 30 expert interviews conducted myself. I tried to find people who are responsible for the revitalization of big industrial spaces which are not in the city center. They have entirely different backgrounds, ranging from architecture to journalism, and from photography to IT. Sometimes they themselves really wondered in which ways they are connected to the creative industry because they just doing their own small business day-to-day jobs and didn’t identify themselves with creative industry as a whole. This is interesting because, in fact, they are the ones creating the creative industry in praxis!

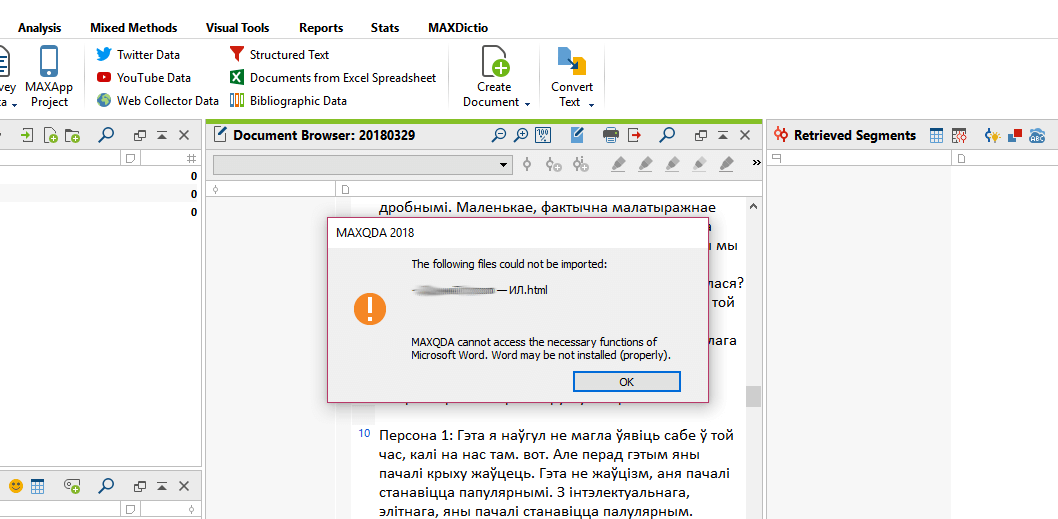

The process of categorizing the interview content must, therefore, begin before you start transcribing your interviews. Raw data needs to be well organized and classified. You can use MAXQDA’s Web Collector to upload a saved text from the web using a Google Chrome extension, just make sure that you have MS Office on your computer. For personal reasons, I use an open source LibreOffice and don’t have MS Office on my computer, so the Web Collector was not able to import my saved page. But the solution was easy and quick: I converted the saved web pages into text files and then imported them into MAXQDA as a regular text document.

Figure 2: Warning window in MAXQDA

Problem #2: interview language

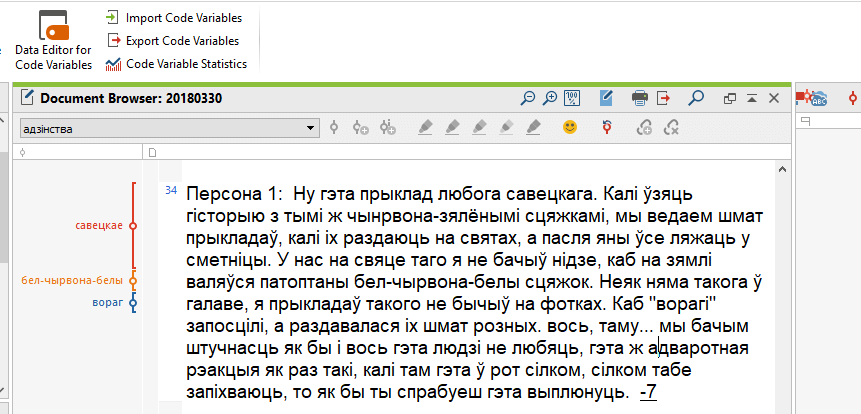

The question of cultural identity in Belarus is, by default, a question about language policy. The 30 experts were interviewed in Belarusian (12 of 30) and Russian languages (18 of 30), and the choice of language was on the respondent’s side. This difference in interview language obviously raises the question of how to work with several languages in one project. Luckily, MAXQDA allows you to work with texts in any language and you can also name your codes in any language you choose as well. And, as I mentioned before, it is possible to separate interviews in the “Document System” window, so you can do that by the criteria of language if you wish to.

Language is a key element in Grounded Theory when looking for possible interpretations. When people work in the same field but use different languages (even in one country at the same period of time) they, in fact, will speak about a different social reality from one another. My final report will be prepared in Belarusian to start with, so I will need to translate the important evidence from selected interview topics from Russian into Belarusian.

Furthermore, the code system in Grounded Theory analysis springs up from the texts itself. I start my research journey without fixed tables of codes and chose the names for codes and categories from the narratives of my respondents. To do so, I used MAXQDA’s “in-vivo coding” function to code my interviews. When the experts articulated important words, I used their specific words as my codes and sometimes later as my categories. It is extremely important for me that I don’t put my own labels and tags on what they are saying, but instead, find and use the words of my respondents from their personal narratives. Also, because they speak different languages, it is more interesting to see what words they use and try to find new meanings for the well-known words, such as a “Soviet” or “language”.

Figure 3: Coding in-vivo in MAXQDA

Problem #3: analysis visualization and discussion with colleagues

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to bring your computer with you to show how your work on a project is progressing when you want to discuss your research with colleagues and consultants. It can turn into a nightmare when you have to literally explain everything on your fingers. Well, especially for such special pedagogical moments, I use the free MAXQDA Reader to share my work with others who do not have MAXQDA at hand.

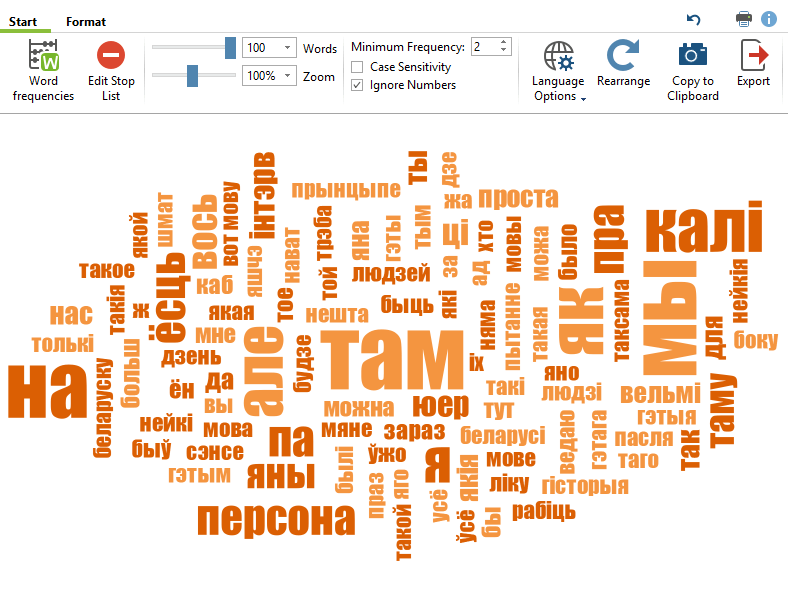

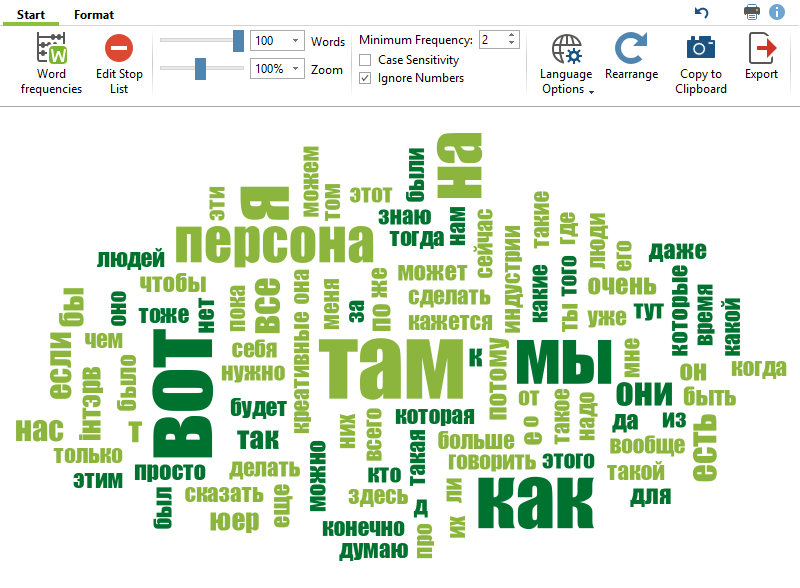

Also very helpful to see visualizations of text analysis. MAXQDA has several capabilities for analysis visualization, and I use, for example, the Word Cloud feature to visualize word frequencies in my interview transcripts. Of course, word clouds are not deep analytical tools, but they are great for visualizing invisible dialog, as is the case in my project.

Words Clouds of Belarusian and Russian texts

What’s Next

I’m looking forward to using MAXQDA’s analysis tools to analyze Twitter content, but that will be an additional side project. Using the script created by Martin Hawksey, I have accumulated about 8,000 posts with the #electby hashtag in the Google cloud. When I began collecting this data, there was not yet a clear understanding of how it could be processed on my side. My plan now is that I will try to compare the discourse on Twitter during the campaigns using MAXQDA’s analysis tools.

Otherwise, I’m still currently in the process of analyzing my empirical data because one can not quickly answer my research question on how a new culture of everyday life is created by creative industries and what their proposed new form of cultural identity is. I do, however, now have a well-grounded hypothesis:

The context of cultural identity today depends on the development of the creative industries, which produce urban culture through rethinking the Soviet past.

When my research project is finalized I will have a more concrete answer. In the meantime, I will continue to work with MAXQDA on my current research project. I just can not imagine how many papers and toner were saved just by using MAXQDA’s analysis tools, instead of printing and paper cutting!

About the Author

Alexei Krivolap is an associate professor at the Department of Finance & Economics, Polatsk State University and a lecturer at the European College of Liberal Arts in Belarus. He graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy and Economics of the Belarusian State University, Department of Cultural Studies. He has a PhD in Cultural Studies (Candidate of Sciences) from the Russian State University for the Humanities. He has won fellowships from the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program, NCEEER – Carnegie Research, and Gräfin-Dönhoff Program. His recent book is titled “Runet: New Constellation in the Internet Galaxy” (in Russian). His scientific interests include: cultural identity, and cultural & internet studies.

Alexei Krivolap is an associate professor at the Department of Finance & Economics, Polatsk State University and a lecturer at the European College of Liberal Arts in Belarus. He graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy and Economics of the Belarusian State University, Department of Cultural Studies. He has a PhD in Cultural Studies (Candidate of Sciences) from the Russian State University for the Humanities. He has won fellowships from the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program, NCEEER – Carnegie Research, and Gräfin-Dönhoff Program. His recent book is titled

Alexei Krivolap is an associate professor at the Department of Finance & Economics, Polatsk State University and a lecturer at the European College of Liberal Arts in Belarus. He graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy and Economics of the Belarusian State University, Department of Cultural Studies. He has a PhD in Cultural Studies (Candidate of Sciences) from the Russian State University for the Humanities. He has won fellowships from the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program, NCEEER – Carnegie Research, and Gräfin-Dönhoff Program. His recent book is titled