The study of the institutionalization of children and adolescents, as well as their outcomes, has accompanied me since my master’s degree in psychology at the Federal University of Bahia. Currently, I have dedicated myself to the adoption process, based on Brazilian public policy, but without disregarding its historical construction, which is often shared in different societies.

One of the relevant fields for psychology refers to the social understanding of adoption. From this study, it is possible to understand the maintenance of stereotypes and even analyze the discourses on which public policies that involve the adoption of children and adolescents are sustained!

In this report, I intend to describe how MAXQDA helped research on perspectives on adoption within the virtual context of YouTube®. I will demonstrate the search procedure and the use of visualization and analysis resources.

Perspectives on adoption

Basically, adoption is divided into two perspectives, considering legal, social, and common-sense discourses. Classic adoption refers to adoption as an instrument to satisfy the needs of a family that, for some reason, wants to have a child: sterility, loss of a child, desire to fulfill a marriage, among others. In the modern adoption view, adoption is understood as a strategy to guarantee the rights of a child or adolescent who does not have a family and, in general, is in a situation of institutionalization and/or vulnerability.

Several authors have questioned the effects of these views on the practices carried out in institutions that intend to provide the rights of children and adolescents, making it increasingly important to understand how positions are sustained and propagated in society (Jacinto & Dazzani, 2020; Nakamura, 2019).

1 – Data collection process: designating and importing video comments

The objective of this study was to identify the positions of internet users who watch content about adoption made available on YouTube with regard to a view of classic adoption and/or modern adoption. To do so, I started with the netnographic method, which seeks to apply principles of ethnography in the virtual context (Kozinets, 2014). YouTube user comments on adoption videos were analyzed.

The following criteria were adopted for inclusion in the selection of videos: having adoption as the main theme, being in a public format, having more than 1000 views, having been published between April and October 2020, presenting journalistic or educational content about adoption. The following were excluded: videos whose authors presented their personal experiences with adoption as central to the narrative, materials not related to the Brazilian reality, with a religious nature, aimed at children, videos aimed at public tenders’ candidates and those focused exclusively on entertainment/humor.

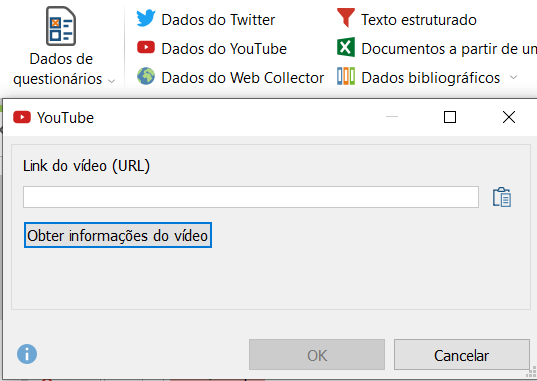

MAXQDA helped a lot in collecting comments from videos. In the Import tab, I selected the option “YouTube Data”. There, I just need to add the link of the chosen video.

Figure 1 – Importing video comments (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 1 – Importing video comments (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

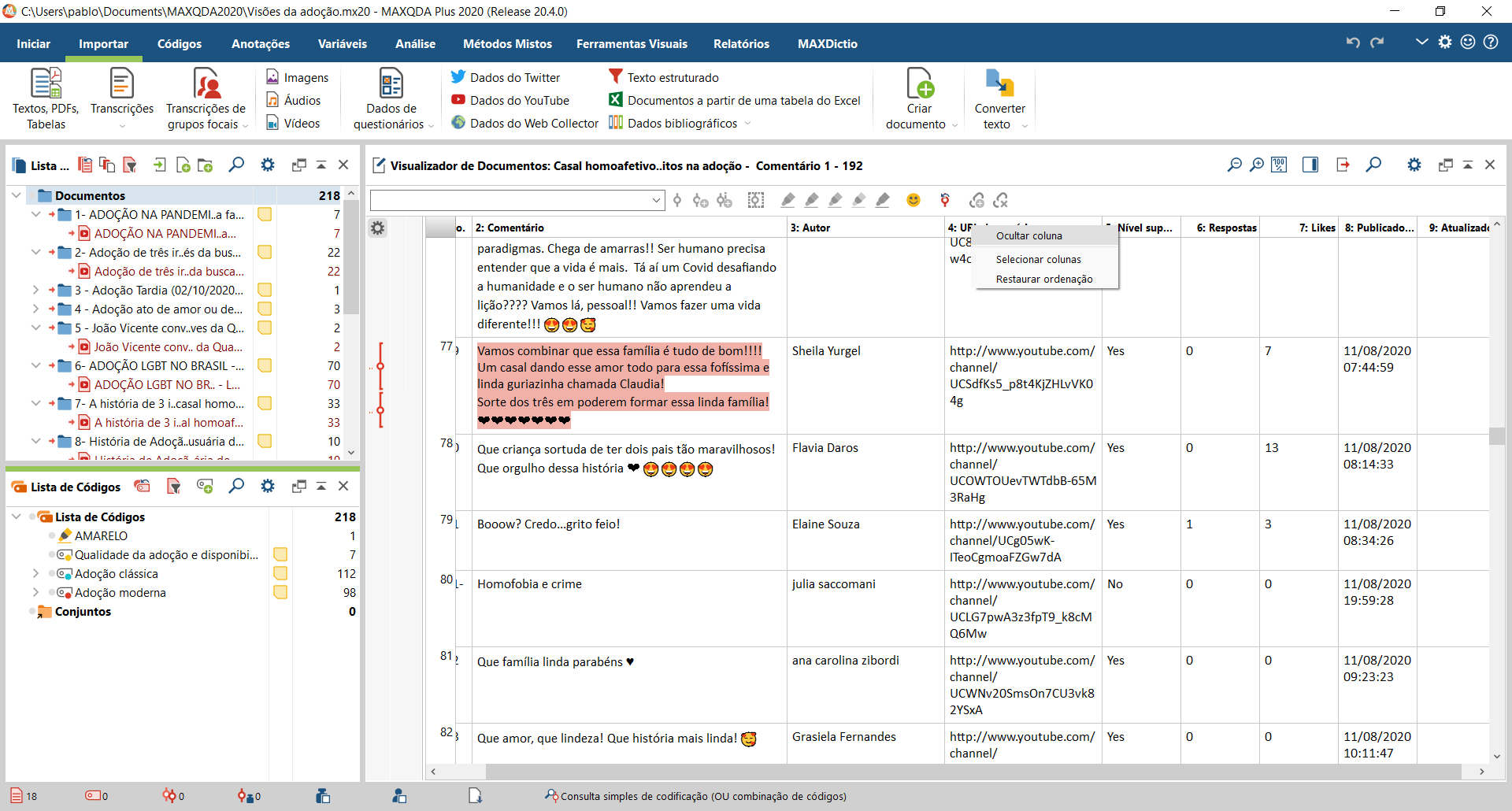

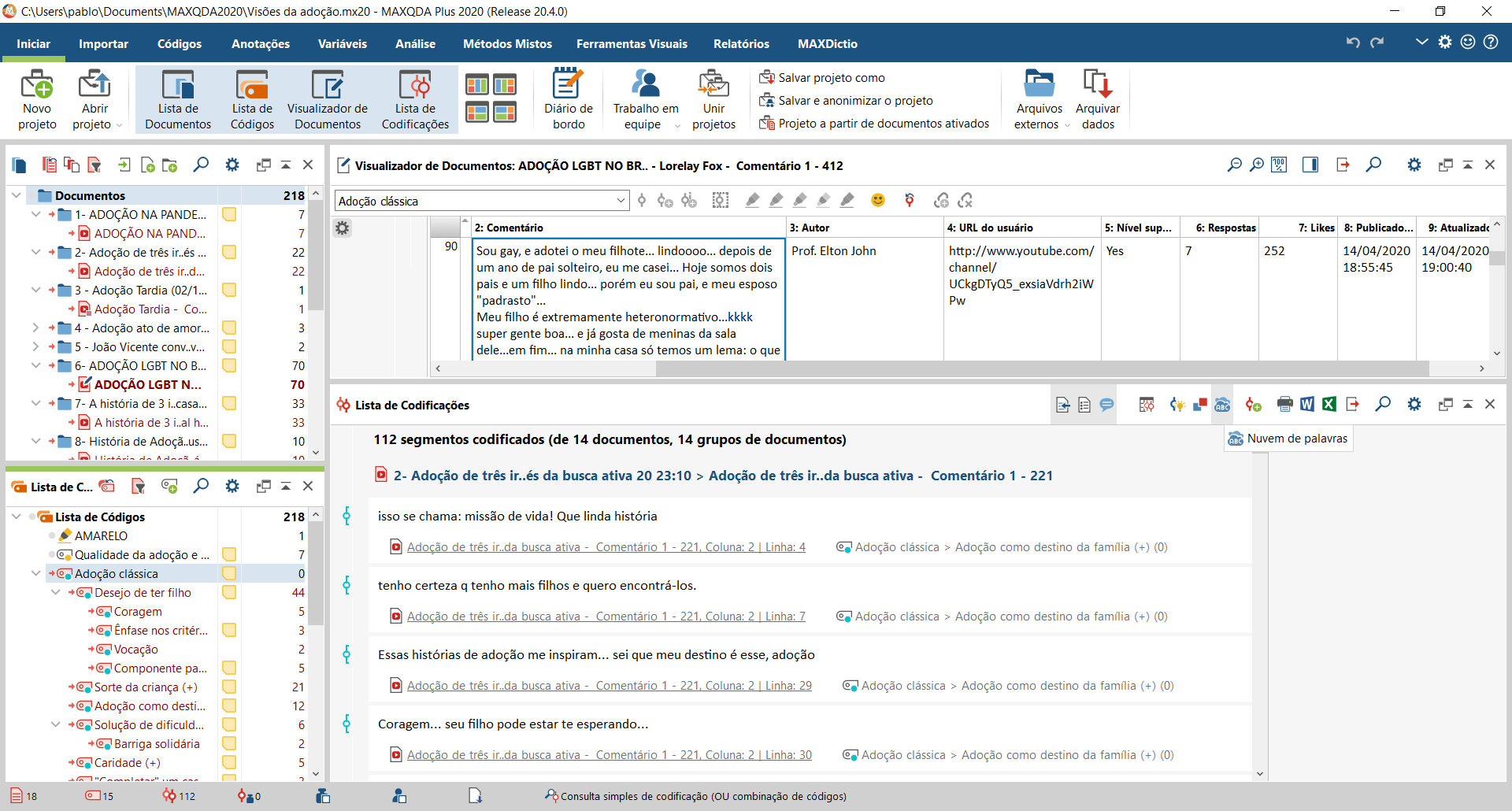

MAXQDA aids the organization of data. In the document window, a new group is added for each video, with the video and possible subtitles as content. In the main window, the collected material is displayed in a table format. As with any table in the software, it is possible to hide unnecessary columns and unhide them when the researcher needs them.

Figure 2 – Comment grid (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 2 – Comment grid (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Importing Youtube Data in the MAXQDA Manual

2 – Coding and categorization: preparing data for treatment

With the aid of the MAXQDA software, the comments of the selected videos were captured and later categorized. Categorization was performed by reading all the comments of the selected videos, forming codes related to classic and modern adoption. Subcodes related to classic adoption were attributed to comments referring to this process from perspectives centered on families, placing the adoptive children as secondary figures who would satisfy the needs of the applicants for adoption. Subcodes were generated for modern adoption, based on those comments centered on the child, understanding their needs and rights as the priority in the adoption process. Parallel to this, I used the Logbook tool to organize impressions about the research and theoretical reflections that arose throughout the entry into the field.

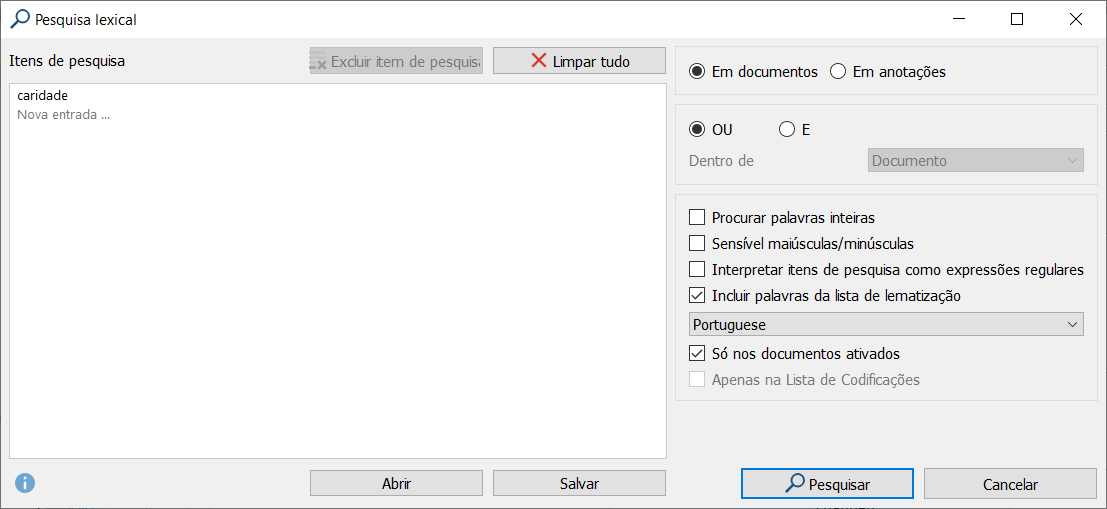

Coding involved Lexical search to search for words commonly associated with categories, such as: dream, charity, and law, among others. The results were autocoded for subsequent verification.

Figure 3 – Lexical search window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 3 – Lexical search window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

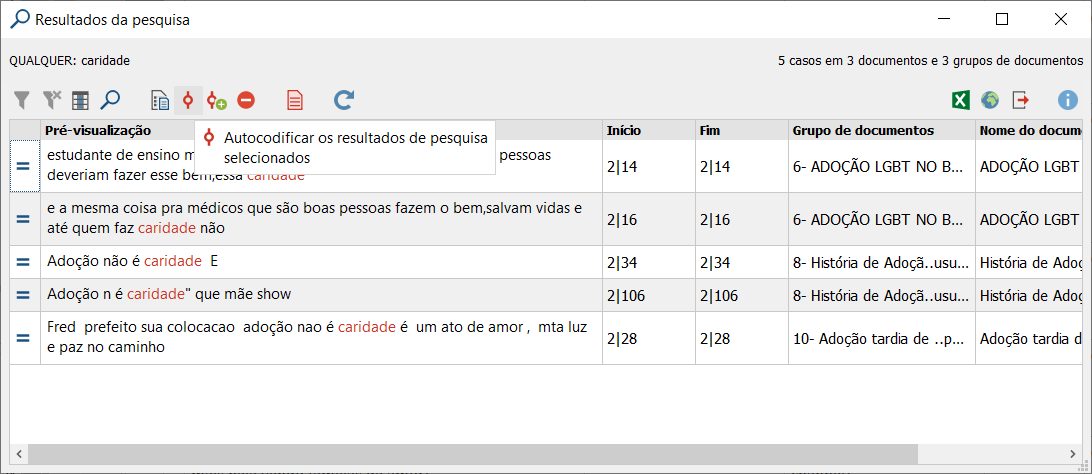

The lemma list resource was fundamental, because it expanded the search beyond the exact word, considering others derived from its radical.

Figure 4 – Lexical Search results with lemma list on (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 4 – Lexical Search results with lemma list on (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Lexical Search in the MAXQDA Manual

The full reading of the comments was performed, accompanied by manual coding. I always chose to code the entire comment and not just the excerpt. This was important to identify the same subject representing different positions and helped in the use of analysis resources, by showing overlaps and proximity to codes.

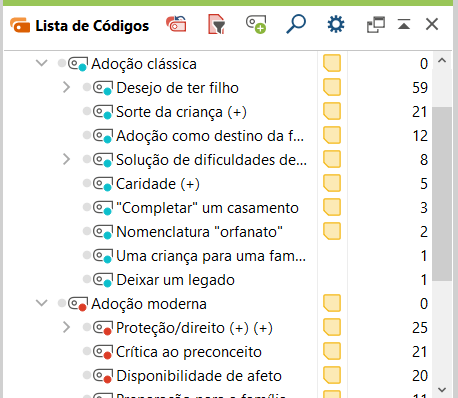

As stated, taking “classic adoption” and “modern adoption” as main codes, I created subcodes that more specifically reflected users’ positions in coded comments. When the position was ambiguous, I created separate codes that would be further refined.

Figure 5 – Code system (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 5 – Code system (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

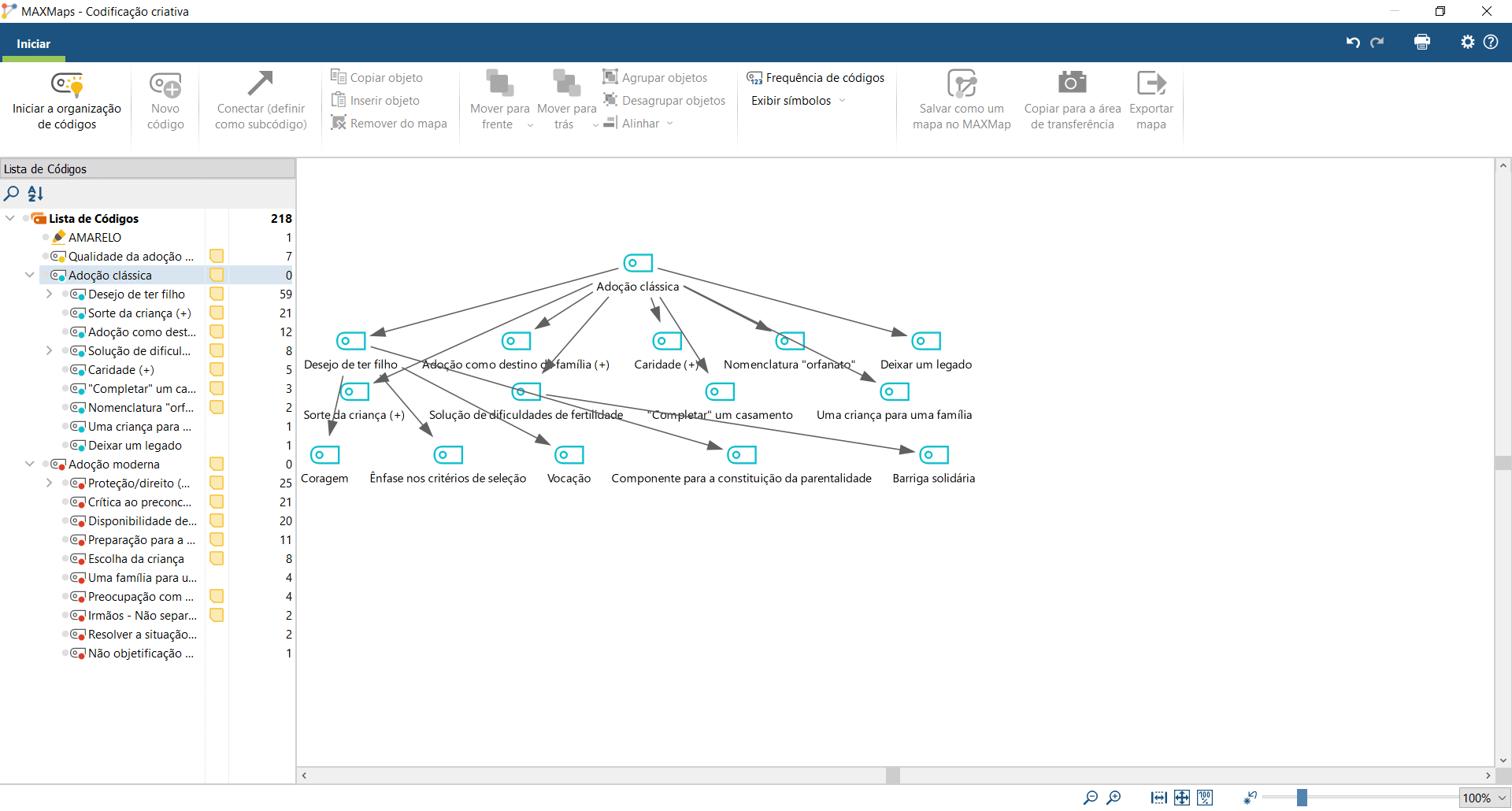

After finalizing the coding process, the Creative Coding feature was used in order to accurately observe each code, merge, and establish necessary connections. For example, it was necessary to merge the codes “charity” and “philanthropy”, because in a later analysis I ended up identifying that their contents were similar.

Figure 6 – Creative Coding window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 6 – Creative Coding window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Creative Coding in the MAXQDA Manual

3 – Analysis: making the most of MAXQDA tools in data visualization

The data analysis included:

- Reading the Code System and Retrieved Segments.

All documents and, subsequently, codes related to classic and modern adoption were selected.

- Working with Word Clouds.

The word clouds were formed with the coded segments, to avoid bias with material from comments that were not relevant to the research.

Figure 7 – Code System and Word Cloud (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 7 – Code System and Word Cloud (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

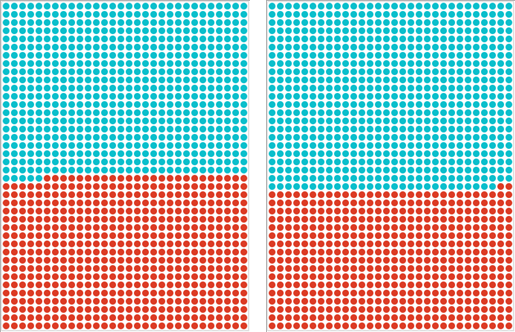

- Creating Document Portraits

This resource allowed me to observe, video by video, which perspective of adoption prevailed.

Figure 8 – Document Portraits: blue = classic adoption; red = modern adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 8 – Document Portraits: blue = classic adoption; red = modern adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Document Portraits in the MAXQDA Manual

- Complex Coding Query

Through the menu Analysis > Complex Coding Query, it was possible to perceive the relationship between coded segments. For example, I carried out a search for proximity, intersection, and overlap in order to observe when the same respondent presented more than one view related to adoption, revealing a complexity in her position.

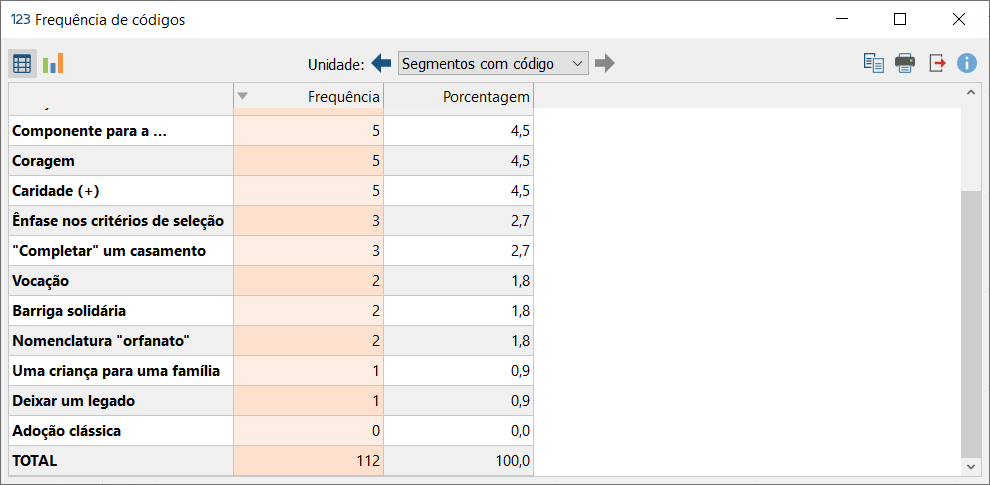

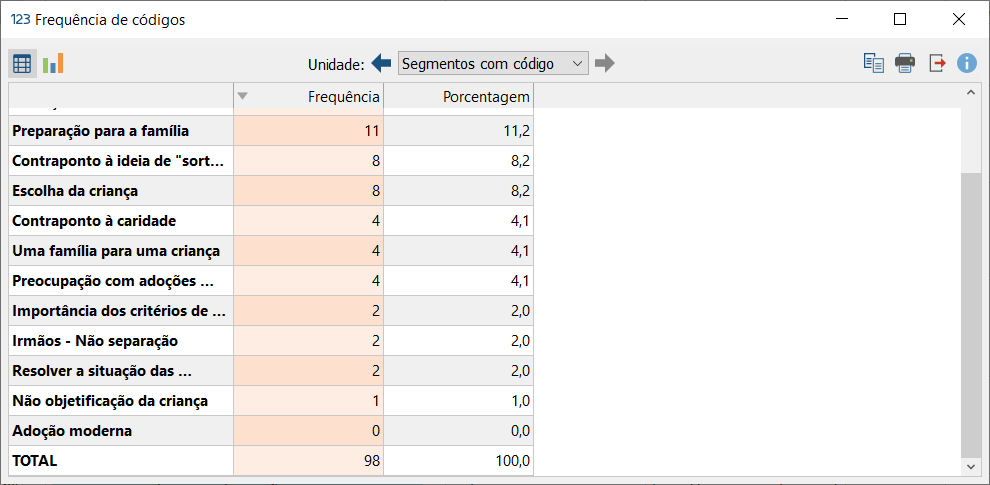

- Code Frequencies

The tool Analysis > Code Frequencies allowed taking a quantitative look at the data, as it aided the visualization of the distribution of each code document by document. It is important to note that this tool can perform calculation with a single document or with all documents activated. Another advantage of the tool is analyzing, for example, the distribution of codes per document or to count their use when observing the coded segments.

Figure 9 – Code Frequencies: classic adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 9 – Code Frequencies: classic adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 10 – Code Frequencies: modern adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 10 – Code Frequencies: modern adoption (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Note: In this case, I chose not to use the summaries feature, as the videos were varied and not all followed the same pattern of responses. Furthermore, because there are many codes displaying great variance among the documents, I thought that comparison via the Summary Explorer would not be ideal.

Code Frequencies in the MAXQDA Manual

4 – Results: what did the research on YouTube reveal about perspectives on adoption?

Table 1 summarizes the completed codification, assigning each subcategory to the criteria of classic or modern adoption. The occurrence refers to the percentage of videos in which each code occurred.

Table 1 – Comment coding

Category | Attributed codes | Occurrence |

Classic Adoption | Desire to have a child | 55,6% |

Child luck | 27,8% | |

Solution of fertility difficulties | 22,2% | |

Adoption as destination | 22,2% | |

Adoption as charity/act of love | 16,7% | |

Complete a wedding | 11,1% | |

Leave a legacy | 5,6% | |

Gift for family | 5,6% |

Modern Adoption | Protection/rights | 50% |

Availability of affection | 44,4% | |

Child’s choice | 33,3% | |

Criticism of prejudice | 27,8% | |

Family preparation | 16,7% | |

Concern about special adoptions | 16,7% | |

Against siblings’ separation | 11,1% |

Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019)

With this, the predominance of the classic view of adoption was identified, assuming this process as a tool to solve the needs of a family. On the other hand, significant positions were observed corroborating a modern view of adoption, understanding this process as a right that aims to guarantee protection to a vulnerable child or adolescent.

It was interesting to note that, in many cases, the positions associated with classic and modern adoption were overlapping or near to one another, sometimes narrated by the same person. In other words, it is not possible to say that society reproduces only a modern view of adoption, but it is also false to say that the way in which participants interpret this practice completely disregards the interests of children.

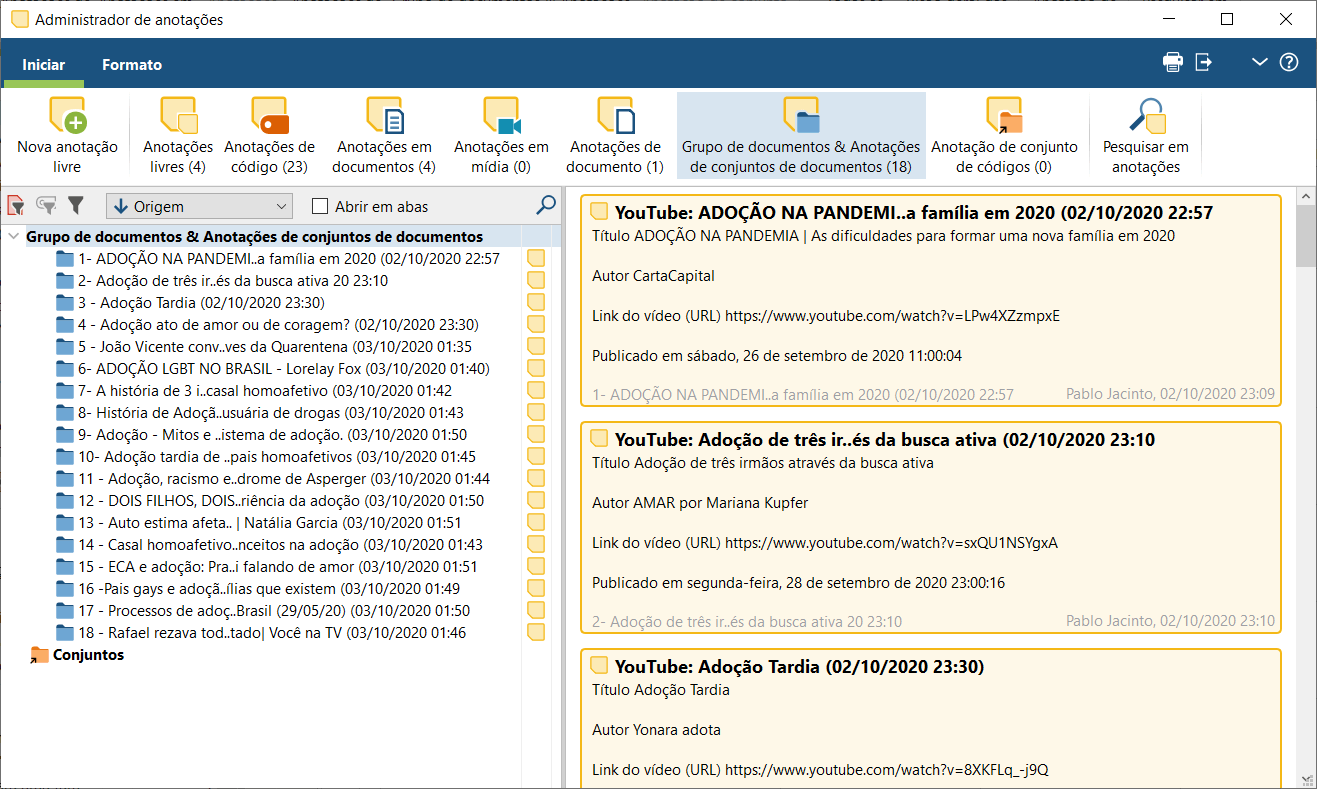

5 – Extra: generating reports and sharing the contents

In the Memo tab, I accessed the option “Document Group & Document Set Memos” to structure the database and present it for review. When importing videos from YouTube, MAXQDA organizes as memos the main information such as: title, authorship, description, URL, among others. These memos can be exported, producing a file in .docx format with this systematized information.

Figure 11 – Memo Manager window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Figure 11 – Memo Manager window (Source: author, extracted from MAXQDA (VERBI Software, 2019))

Sobre o Autor

Pablo Mateus dos Santos Jacinto is a MAXQDA trainer, and currently a doctoral candidate in Psychology at the Federal University of Bahia, Brazil. A defender of childrens’ and adolescents’ rights, he has carried out research on narratives and public policies about adoption and family.

References

Jacinto, P. M. dos S., & Dazzani, M. V. M. (2020). Acolhimento institucional e desinstitucionalização: uma revisão integrativa de literatura em psicologia (Institutional sheltering and deinstitutionalization: an integrative review in psychology). Emancipação, 20, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.5212/Emancipacao.v.20.2016477.026

Kozinets, R. V. (2014). Netnografia: realizando pesquisa etnográfica online. Porto Alegre: Penso.

Nakamura, Carlos Renato. (2019). Criança e adolescente: sujeito ou objeto da adoção? Reflexões sobre menorismo e proteção integral. Serviço Social & Sociedade, (134), 179-197. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-6628.172

VERBI Software. (2019). MAXQDA 2020 [computer software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software. Available from maxqda.com.