Release date: 28.01.2026

Stories shape our lives. They help us make sense of who we are, what happened, and why it matters. We rely on stories in job interviews, on social media, and in therapy sessions. Stories help us frame experience, connect with others, and navigate the world. But stories are not neutral accounts. They are selective and shaped by cultural discourses, institutional contexts, and relations of power. In qualitative research, these everyday narratives become data.

Narrative analysis offers a rigorous framework for engaging with stories as empirical material. It does not reduce narratives to isolated themes or decontextualized fragments. Instead, it examines how stories are constructed and what those stories mean to the people who tell them. It also asks how narratives reflect and shape the social worlds in which they circulate. This approach emphasizes both the structure and context of storytelling. It asks not just what was said, but how, to whom, and for what purpose. These elements reveal how meaning, identity, and social positioning are produced and negotiated through narrative.

Whether you are a graduate student, a researcher, or a practitioner, this guide introduces the core traditions of narrative analysis: thematic, structural, and dialogical. Each offers a distinct lens for uncovering meaning in narrative data. You will find clear explanations, step-by-step guidance, and practical tools for working with interviews, case studies, and other narrative forms.

What is Narrative Analysis?

Narrative analysis is a family of qualitative methods focused on studying stories as they’re told by research participants.

Unlike other qualitative approaches that break data into thematic fragments, narrative analysis treats stories as meaningful wholes. You examine not just what people say, but how they say it, why they structure their stories in particular ways, and what these storytelling choices reveal about their meaning-making processes, identity, and social contexts.

More broadly, narrative analysis engages with what Jerome Bruner called the "narrative construction of reality": stories don't simply reflect experience; they help organize it and make it intelligible.

Practically, this means you can look at narratives through two complementary lenses:

- Experience and interpretation: how people select events and confer subjective meaning on them.

- Narrative means: the linguistic and cultural resources (e.g., metaphors, scripts, familiar plotlines) used to build that meaning.

So when someone describes a challenge, they're not merely recounting facts; they’re shaping how the experience should be understood—often in ways that draw on broader cultural narratives.

Epistemological Note

Different Traditions, Different Assumptions

Narrative analysis isn’t a single technique. It’s a set of approaches grounded in different assumptions about knowledge and reality.

- Phenomenological: narratives as routes into lived experience.

- Constructionist: stories as discursive tools shaped by language, culture, and power.

- Interactionist / dialogical: narratives as performances co-produced in social interaction.

Choose an approach that fits your research questions—and your view of what narratives can legitimately tell you.

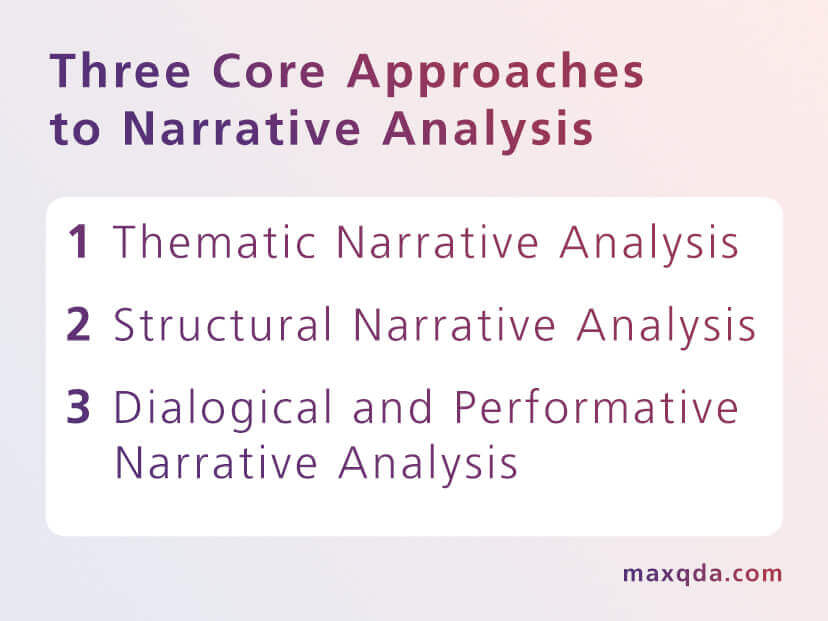

Three Core Approaches to Narrative Analysis

There's no one-size-fits-all recipe for narrative analysis. Instead, your research questions and objectives will help you determine the right analytical approach.

The three main traditions focus on different narrative aspects:

1. Thematic Narrative Analysis

What it focuses on: The content and meaning of stories; what the story is about.

Thematic narrative analysis studies the themes, topics, and issues that emerge across participants' stories. You're looking for patterns in the substance of what people talk about: What experiences do they describe? What meanings do they attach to these experiences? What common threads connect different people's narratives?

When to Use It

- You want to understand common experiences across multiple participants

- Your research questions focus on the content and meaning of experiences rather than storytelling structure

- You're working with large datasets where you need to identify patterns across many narratives

Example research question

"How do cancer survivors make sense of their recovery experiences?"

2. Structural Narrative Analysis

What it focuses on: The form and organization of stories; how the story is told.

What Is Structural Narrative Analysis?

Structural analysis examines how narratives are constructed: their plot structures, temporal sequences, turning points, and narrative devices. You pay attention to elements like how the story begins and ends, how events are ordered, what gets emphasized or minimized, and how tension builds and resolves. The structure itself reveals meaning.

When to Use It

- You're interested in storytelling as a social and cultural practice

- You want to understand how narrative form shapes meaning

- You're comparing how different groups or cultures structure similar experiences

- You're examining turning points, transitions, or transformations in life stories

Example research question

"How do teachers structure narratives of career transitions, and what do these structures reveal about professional identity?"

3. Dialogical and Performative Narrative Analysis

What it focuses on: The interactive context in which stories are told; who tells the story, to whom, why, and with what effects.

What Is Dialogical Narrative Analysis?

Dialogical approaches, such as Arthur Frank's (2010) Dialogical Narrative Analysis, view narratives as performances that occur in specific social contexts. You examine the storytelling event itself: How does the narrator position themselves in relation to their audience? What social and cultural narratives do they draw on or resist? How does the telling of the story accomplish social actions such as building identity, claiming legitimacy, or challenging assumptions?

When to Use It

- You're interested in identity construction and social positioning

- You want to understand power dynamics in storytelling

- Your data involves interaction (interviews, focus groups, naturally occurring conversations)

- You're examining how narratives circulate in and influence communities

Example research question

"How do asylum seekers position themselves and their experiences when telling their stories to immigration officials versus peer support groups?"

How to Choose and Combine Approaches

Choosing Your Narrative Analysis Approach

To help guide your choices, consider your research questions, the nature of your data, and the understanding you seek to gain.

- Choose thematic analysis if you're exploring common themes across a broad set of narratives.

- Opt for structural analysis when you're interested in how stories are told, such as their sequencing, turning points, and narrative arcs.

- Use dialogical or performative analysis when you're examining storytelling as a social act, paying attention to audience, identity, and cultural positioning.

Can You Combine Narrative Analysis Methods?

Why Combine Narrative Analysis Approaches?

It’s often helpful to begin with a single analytic lens, but intentionally combining approaches—when guided by theoretical and methodological clarity—can yield richer, more nuanced interpretations. Narrative analysis traditions are grounded in distinct epistemological assumptions about what stories are and what they do: themes point to meaning; structure reveals narrative logic; performativity exposes social positioning. Therefore, integration should not be a matter of convenience or aesthetic preference, but of analytical rationale.

How to Combine Them Thoughtfully

For instance, you might begin with a thematic analysis to identify shared experiences across interviews, then engage in structural analysis to explore how those experiences are temporally and affectively organized in narrative form. Finally, a dialogical lens may help you examine how storytellers position themselves and their audiences within these narratives. This process can reveal power dynamics or identity claims embedded in the act of narration itself. This kind of integration reflects a hermeneutic orientation, valuing interpretive depth and reflexivity over methodological purity, but it must be methodologically intentional. Not all narrative researchers support methodological blending, particularly when analytic lenses rest on different assumptions about what narratives are and what they do. Where integration is pursued, it should be guided by clear theoretical reasoning.

The key is to explain how each lens advances your interpretive goals and how their combination adds clarity rather than complexity to your analysis. Integration is most effective when it is guided by your research questions and theoretical commitments, rather than by a desire to address every possible angle.

A 3-Level Listening Framework

Think of it as tuning into a story on three interrelated frequencies, drawing on typologies developed by narrative methodologists such as Catherine Riessman (2008):

- What’s being said (thematic)

- How it’s being told (structural)

- Why it’s being told this way, and to whom (dialogical/performative)

When applied with epistemological awareness, combining approaches can reveal narrative complexity that any single method might miss, particularly when your goal is to understand stories as both texts and as practices of making meaning within specific times, discourses, and social contexts.

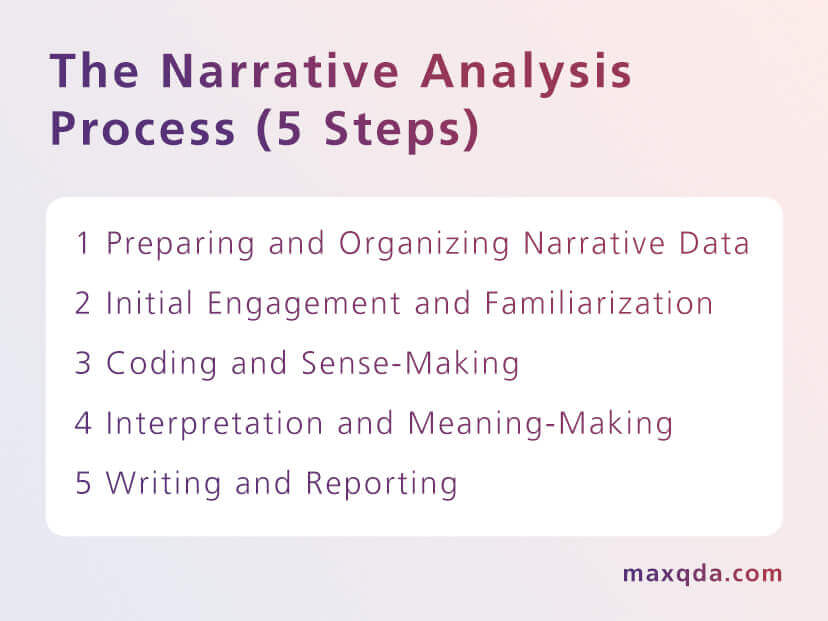

The Narrative Analysis Process

While specific techniques vary depending on your chosen approach, most narrative analysis projects follow a similar general process. Here's how to move systematically from raw data to meaningful findings:

Step 1: Preparing and Organizing Narrative Data

Narrative analysis works with various data types: interview transcripts, written autobiographies, social media posts, organizational documents, field notes from ethnographic observation, and more. Your first task is to organize and prepare this material for analysis.

Key activities:

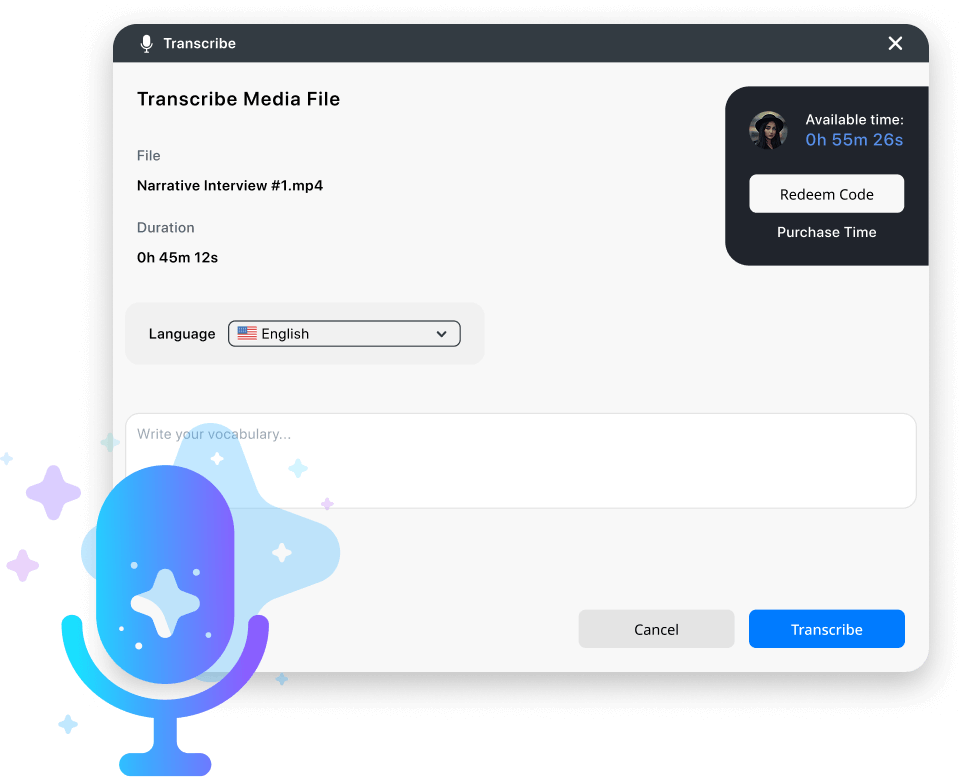

- Transcribe audio or video recordings if needed, paying attention to pauses, emphasis, and other performative elements if you're doing dialogical analysis

- Organize your documents in a logical structure (by participant, by data collection phase, by document type)

- Read through all materials to get an initial sense of the data

- Identify the boundaries of narratives. Where does one story begin and end?

Capturing Performative Elements in Transcription

Transcription for narrative analysis poses distinct challenges. If you're doing dialogical analysis, performative elements matter: a three-second pause may signal emotional weight or careful reflection, while rapid-fire speech might indicate defensiveness or excitement. Speaker changes are analytically crucial, as positioning happens in the interactional flow between voices. Yet manual transcription that captures these details is extraordinarily time-consuming, and generic transcription services often flatten these elements.

MAXQDA's automatic transcription addresses this by systematically preserving what narrative analysts need: speaker changes are detected automatically and each speaker's contributions are maintained as distinct units (essential for tracking positioning strategies), pauses are noted with precision distinguishing 1, 2, and 3+ second silences (making emotional and reflective moments visible in the text), and timestamps are embedded throughout, allowing you to return to the original audio during interpretation to hear vocal tone, emphasis, or hesitation that written words can't fully capture.

Organizing Narratives by Analytical Context

To prepare effectively, you need to track the context of each narrative. For example, the career transition story of a 45-year-old teacher will have a different meaning than that of a 25-year-old. Narratives collected during initial interviews may also differ from those in follow-up conversations. These differences are not just background details; they're important analytical variables that influence interpretation.

With MAXQDA's Document variables, you can assign this type of information directly to each document. Later, when you're deep in interpretation, you can activate only narratives from specific subgroups (all participants over 40, or all second-wave interviews), compare patterns across demographics, or test whether themes differ by interview phase. This transforms demographic information from static metadata into active analytical tools. The Document System supports both hierarchical organization (document groups that function like folders) and flexible, overlapping collections (document sets), which matters when narratives need to belong to multiple analytical categories simultaneously.

Step 2: Initial Engagement and Familiarization

Before jumping into formal analysis, immerse yourself in the narratives by reading them closely and reflectively. Pay attention to what draws your eye, such as unusual details, recurring themes, or moments that seem especially significant. This early engagement helps you notice the patterns, surprises, and puzzles that will shape your later analysis.

Key activities:

- Read each narrative multiple times, first for overall sense and then with increasing analytic attention

- Write initial reflections about what strikes you, what seems significant, what raises questions

- Note your own reactions and assumptions; these are data too, revealing how narratives work on audiences

- Begin to develop hunches about patterns, themes, or structures

Why Early Impressions Matter

This immersive phase generates crucial but often fugitive analytical thinking. Initial reactions reveal how narratives work on audiences, including yourself as a researcher. Hunches about patterns are valuable, but only if you can remember them weeks later when you're deep in coding. Distinguishing between "this surprises me," "this is a methodological question," and "this might be a theoretical connection" matters because these different types of thinking serve distinct analytical roles. Yet researchers often lose these early findings, or end up with notebooks full of undifferentiated observations they can't make sense of later.

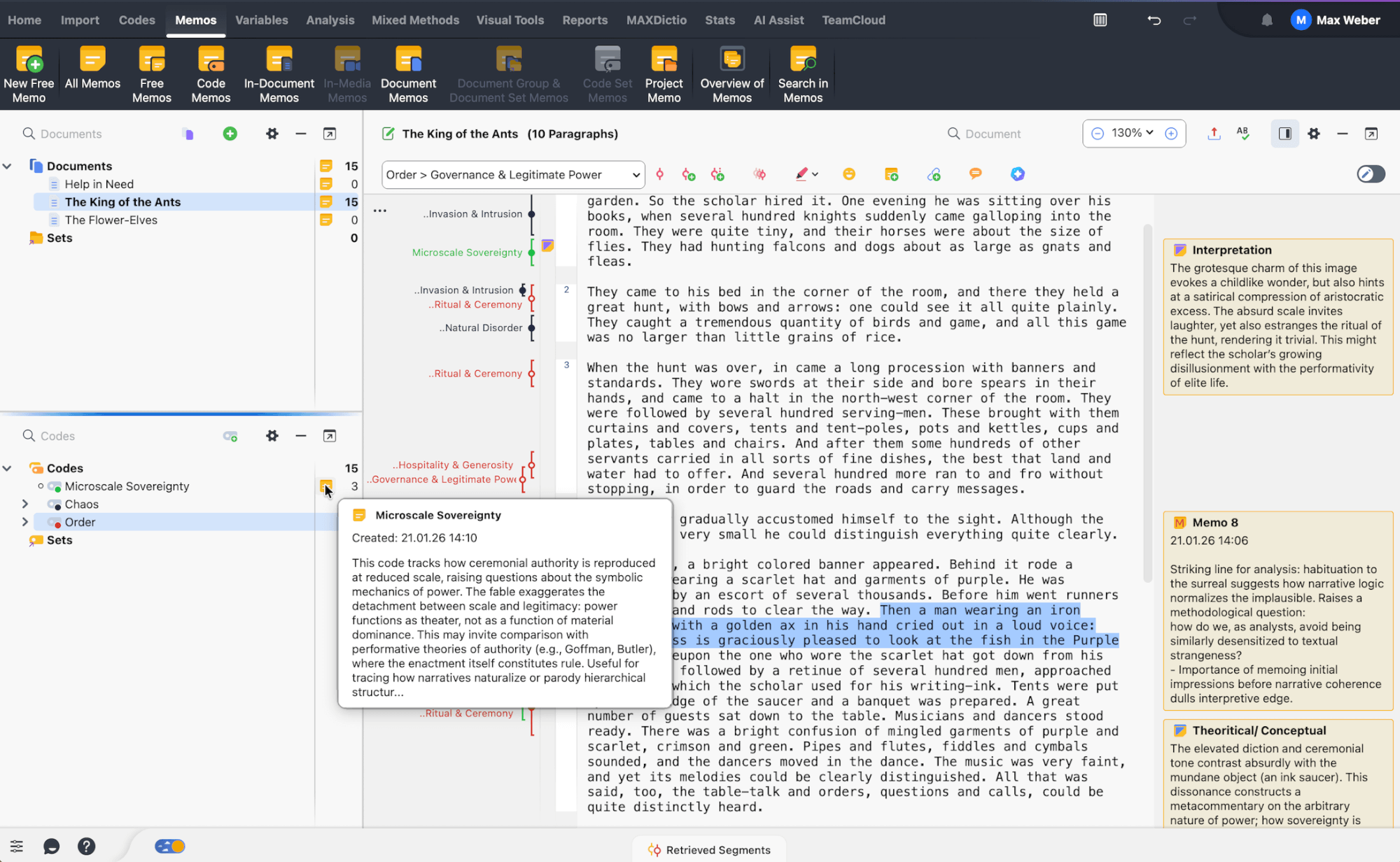

How to Capture and Use Memos Effectively

MAXQDA's memo system captures this thinking systematically as it emerges. In-document memos attach to specific passages, anchoring your reactions to the exact narrative moment that triggered them. When you return to that passage during coding, your initial response is still there, available for reconsideration. Document-level memos record overall impressions of each narrative as a whole, while free memos capture cross-narrative hunches before you can pin them to specific segments. Ten different memo symbols let you mark reflections by type: surprises, methodological notes, theoretical connections, or emotional reactions. This visual distinction means that three months into your project, you can filter to see only your methodological questions, or trace all the moments that surprised you, revealing patterns in your own analytical attention.

Because memos remain editable and searchable, they become a living record of your evolving engagement. The Memo Manager lets you review all memos together, search their content for recurring concerns, and track how your thinking developed over time. This creates an audit trail not just of your conclusions, but of the interpretive process itself, supporting the transparency that qualitative rigor requires. The Logbook complements this with date-stamped entries documenting decisions about procedure, sampling, or analytical direction.

Identifying Narrative Boundaries Systematically

For the practical work of identifying narrative boundaries, MAXQDA's text search functions locate markers systematically across your entire dataset. Rather than manually hunting for phrases like "So this one time" or "I remember when" in each transcript, you can search all documents simultaneously, seeing every instance of temporal markers, story openings, or closing phrases. This systematic approach helps ensure you're identifying boundaries consistently across cases rather than idiosyncratically based on which markers happened to catch your attention in each text.

Step 3: Coding and Sense-Making

Now you begin systematic coding, though what you code and how you code depends on your analytic approach:

- For thematic analysis: Code for content themes, topics, experiences, and meanings. You might use codes like "barriers to care," "turning points," "family support," or "identity transformation."

- For structural analysis: Code for narrative elements and structures. You might identify "abstract," "orientation," "complicating action," "evaluation," "resolution," and "coda" (following Labov's (1972) narrative structure), or code for "metaphors," "temporal markers," "plot types," or "narrative devices."

- For dialogical analysis: Code for positioning strategies, audience references, social discourses drawn upon, and performative elements. You might use codes like "self-positioning as expert," "resistance to stigma," "appeal to medical authority," or "use of collective identity."

Key activities:

- Develop your coding scheme based on your research questions and chosen approach

- Apply codes systematically across your dataset

- Refine codes as patterns emerge (this is an iterative process)

- Write code memos defining what each code means and tracking how your understanding evolves

- Look for both patterns (what repeats) and variations (what differs)

Managing Multi-Layered Narrative Codes

Narrative coding presents distinct challenges. Stories operate at multiple levels simultaneously: a passage might describe a specific event (content), use a redemption plot structure (form), and position the speaker as someone who overcomes adversity (function). You need overlapping codes because that single passage serves all three analytical purposes. Your codes also need to reflect hierarchical relationships: "identity work" might encompass "positioning as expert," "positioning as victim," and "positioning as survivor" as subcodes. And because narrative analysis is iterative, you'll discover that your Week 1 understanding of what "turning point" means has evolved by Week 8, requiring you to reconsider earlier coding decisions.

MAXQDA's hierarchical code system handles this complexity. Parent codes and subcodes can nest multiple levels deep, mirroring how narrative meaning operates at different scales. The system manages overlapping codes naturally: when you assign three codes to the same passage, it's capturing that passage's multiple functions, not creating redundancy. Color coding adds visual distinction; you might use one color family for content themes, another for structural elements, and a third for positioning strategies, making it immediately visible which analytical lens each code represents.

In MAXQDA, in-vivo coding creates codes directly from participants' own language, preserving the distinctive phrases that become analytically important. When a participant says, "I'm not the kind of person who gives up," that exact phrasing might matter more than your paraphrase "persistence," because it reveals how they're constructing identity through narrative. Code memos and code comments document your evolving understanding of what codes mean: when "turning point" initially captured only dramatic events but later expanded to include quiet realizations, that definitional evolution is recorded, creating transparency about how your analytical framework developed.

Refining Codes Through Iterative Review

Critically, the Smart Coding Tool supports the iterative refinement that narrative work requires. After your initial coding pass, you can use it to locate all instances of specific patterns or phrases, checking whether you've applied codes consistently across cases. When your understanding of a concept deepens, you can systematically review previously coded segments, refining your analysis while ensuring you don't lose sight of earlier interpretations. This addresses Smith's warning about over-coding: you can check whether you're fragmenting stories unnecessarily and adjust your approach to keep narratives more intact.

Paraphrases complement coding by letting you create concise summaries of longer narrative segments. When a three-paragraph story illustrates a turning point, the paraphrase captures its essence in a sentence or two, allowing you to see patterns across cases without losing the connection to the full narrative context.

Step 4: Interpretation and Meaning-Making

Coding organizes your data, but interpretation is where analysis deepens. Now you move beyond identifying patterns to understanding what they mean and why they matter.

Key activities:

- Examine coded segments together to develop a richer understanding of patterns

- Write analytical summaries of key themes or structural patterns

- Compare narratives across participants, looking for variations and what explains them

- Connect your findings to theoretical frameworks and existing research

- Consider alternative interpretations and what evidence supports different readings

- Reflect on what narratives reveal about broader social and cultural contexts

Ethical Reflexivity Tip

Narrative analysis always involves interpretation, selection, and re-presentation. Because stories are bound up with identity, power, and lived experience, researchers should pause periodically to reflect on the ethical implications of their analytic choices. When analyzing or reporting narratives, ask yourself:

- Would the participant recognize themselves in my interpretation?

- Am I reducing a complex person to a symbolic case or illustrative example?

- How might my own social position, assumptions, or institutional role be shaping how I hear and interpret this story?

Treating these questions as part of the analytic process, rather than as an afterthought, helps ensure that narrative analysis remains both methodologically rigorous and ethically responsible.

Comparing Across Cases While Preserving Context

Interpretation requires holding two things in tension: the particularity of individual narratives and the patterns that emerge across cases. You need to see all instances of "turning points" together to understand how they function across your dataset, but you also need to remember that Maria's turning point happened during her mother's illness while James's occurred during graduate school, and that context shapes meaning. Generic thematic analysis tools often collapse this context, pulling decontextualized quotes into piles. Narrative analysis involves preserving the link between patterns and their context.

The Overview of Coded Segments retrieves all segments coded with particular codes while maintaining source information for each. You can immerse yourself in all "turning point" segments together, but still see which participant's narrative each came from and where it appeared in their story's arc. To systematically compare across theoretically meaningful subgroups, MAXQDA's activation system connects back to the variables you assigned in Step 1. Want to compare how male and female participants structure career transition narratives? Activate only female participants, examine the pattern, then activate only male participants and compare. The variables transform from metadata into active analytical tools, enabling theory-driven comparison. Document sets offer a temporary grouping mechanism: create a set of "redemption narratives," another of "contamination narratives," and see which participants' stories belong to multiple sets, revealing complexity.

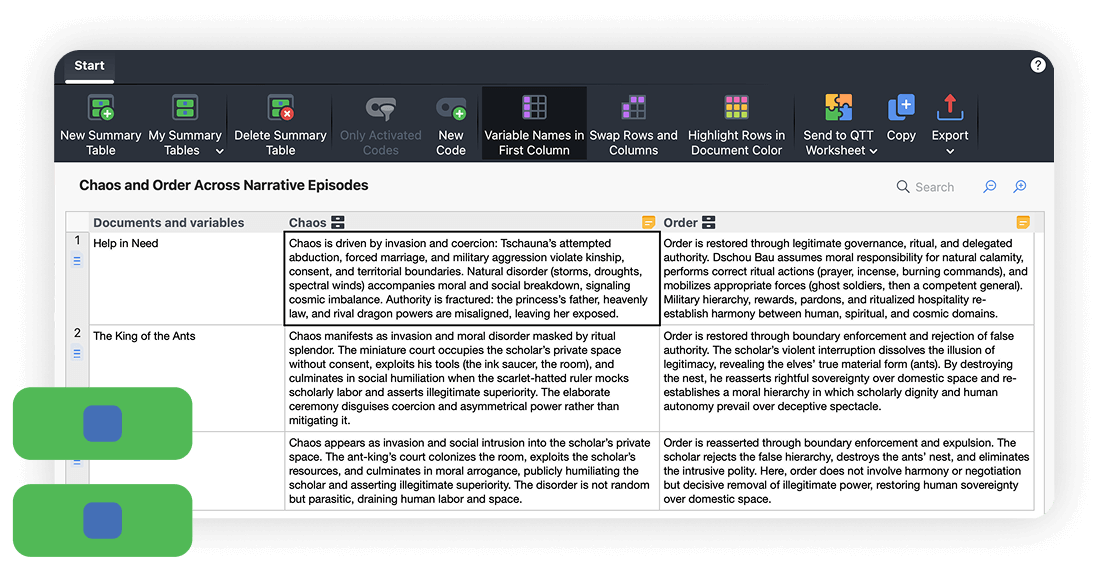

The Summary Grid: Systematic Case-Level Interpretation

MAXQDA's Summary Grid is a particularly powerful tool for narrative interpretation. Here's why: traditional coded segment retrieval gives you fragments organized by theme. You can see all the "turning point" segments, then all the "identity transformation" segments, but you lose sight of how these themes connect within individual narratives. The Summary Grid solves this by creating a matrix where rows are individual participants and columns are your analytical dimensions (themes, structural elements, or interpretive questions).

In each cell, you write an interpretive summary: not just what a participant said about turning points, but your emerging sense of what that turning point meant in their story. This is interpretive work, not just data extraction. As you fill out the grid, patterns emerge: five participants had turning points involving loss. Three saw loss as liberation, while two saw it as devastation, which was connected to earlier narrative positioning. The grid preserves each narrative's integrity (read across a row for one person’s story structure) while enabling comparison across cases (read down a column to see how participants handled the narrative climax). This approach strikes the balance narrative analysis needs, honoring individual stories while revealing patterns. The summaries also become material for writing, capturing interpretations in real time instead of requiring reconstruction later.

Step 5: Writing and Reporting

The final stage involves communicating your findings. In narrative analysis, this often means balancing two tensions: presenting individual stories in their richness while also identifying patterns across stories, and staying close to participants' own words while providing meaningful interpretation.

Key activities:

- Select exemplar narratives that illustrate key findings

- Decide how to present narratives, whether as extended case studies, shorter excerpts, or synthesized patterns

- Provide enough context for readers to understand the storytelling situation

- Balance description with interpretation

- Make clear what analytic lens you're using and how it shaped your findings

- Discuss what your findings contribute to the understanding of the research topic

Synthesizing Multiple Analytical Layers

Writing narrative analysis involves a different kind of synthesis than other qualitative methods. Rather than simply choosing representative quotes, you demonstrate how narratives operate. This means drawing on multiple layers of material: the narratives themselves, your memos documenting how these narratives affected you, your paraphrases capturing story arcs, your code comments tracking how your understanding evolved, and your summary grid interpretations showing patterns across cases. Synthesis means weaving these layers together to tell a compelling and trustworthy analytical story.

MAXQDA supports this by making your accumulated analytical work accessible when you write. The memos you wrote during initial engagement remind you which passages struck you and why. The paraphrases help you describe narrative arcs concisely. The code comments show readers (and reviewers) that "turning point" had a specific, consistent meaning in your analysis. The summaries from your Summary Grids become the basis for case descriptions or cross-case comparisons. You're not starting from scratch; you're synthesizing material you've been developing throughout the analytical process.

Maintaining Transparency and Rigor

For transparency and trustworthiness, readers need to evaluate your interpretive claims against evidence. MAXQDA's export functions maintain the connections between interpretation and source material. You can export coded segments with participant identifiers and source locations, so when you make a claim about patterns in career transition narratives, the supporting evidence includes who said what and where. Formatted reports organize quotes thematically while preserving source context. Summary table exports pull your grid interpretations into draft documents. And crucially, you can export your memo trail, demonstrating that your interpretations emerged through systematic engagement over time, not post-hoc storytelling about your data.

This audit trail matters methodologically since qualitative rigor isn't about eliminating subjectivity but demonstrating that your interpretations are grounded in a systematic process. When you can show how your thinking evolved from initial reactions through iterative coding to final interpretation, supported by dated logbook entries and searchable memos, you're making your analytical work visible and trustworthy.

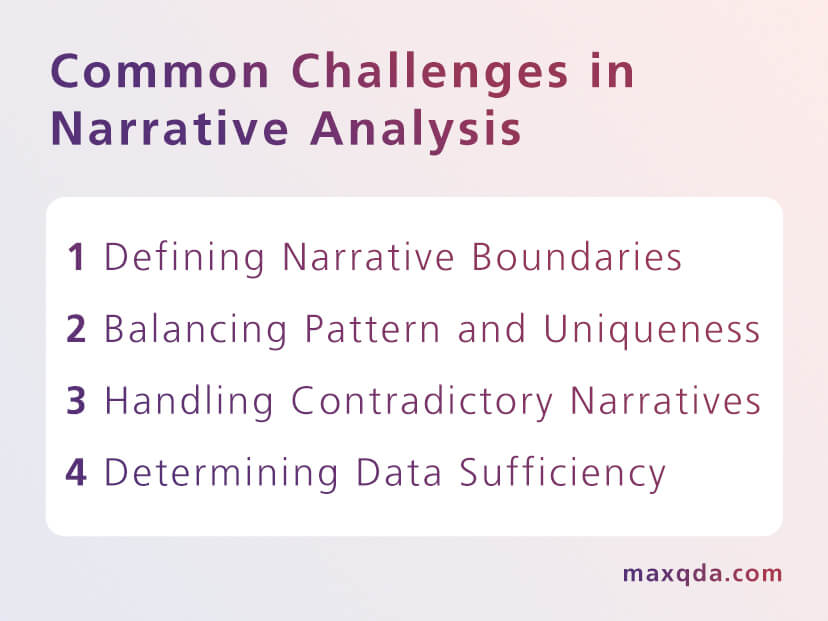

Common Challenges in Narrative Analysis (and How to Address Them)

Challenge 1: Defining Narrative Boundaries

The problem: Where does one narrative end and another begin? In a two-hour interview, there might be dozens of mini-narratives embedded in a broader conversation.

Solutions:

- Look for narrative markers like shifts to past tense, temporal sequences, or story openings ("So this one time...")

- Begin from your research questions, then decide on the narrative scale. Are you tracing brief anecdotes, or working with extended life stories?

- When boundaries are fuzzy, err on the side of including context. You can always narrow later.

Challenge 2: Balancing Pattern and Uniqueness

The problem: Narrative analysis values both individual stories and patterns across stories, but emphasizing one can obscure the other.

Solutions:

- Present your findings at multiple levels. Discuss patterns but illustrate them with specific, richly described narratives.

- Actively look for counter-narratives that don't fit dominant patterns and discuss them explicitly

- Consider your research purpose. Studies documenting narrative diversity should highlight unique cases. Studies identifying typical patterns should show both the pattern and variations from it

Challenge 3: Handling Contradictory Narratives

The problem: The same participant might tell different versions of events at different times, or different participants might offer conflicting accounts.

Solutions:

- Remember that narratives are not true or false, but meaningful. Contradictions themselves are data.

- Examine what motivates different tellings, such as different audiences, different purposes, or different temporal distances from events.

- Code for narrative consistency/inconsistency to track this systematically

- In dialogical analysis, contradictions reveal how people position themselves differently in different contexts

Challenge 4: Determining Data Sufficiency

The problem: Narrative analysis is intensive, and it's not always clear when you've collected sufficient data.

Solutions:

- Focus on depth over breadth: Narrative analysis of 15 in-depth interviews can yield more illumination than superficial analysis of 30.

- Apply the concept of saturation thoughtfully: For thematic analysis, it means no new themes emerge. For structural analysis, it means you've seen the range of narrative forms. For dialogical analysis, it might mean you've captured diverse positioning strategies.

- Let your research questions guide you: If you're making claims about patterns across groups, you need more cases than if you're conducting an in-depth analysis of narrative structures within a smaller sample.

- Be transparent about your dataset's scope and what claims you can and cannot make

Getting Started with Your Own Narrative Analysis

If you're ready to begin a narrative analysis project, here are the next steps:

- Clarify your research questions. What do you want to understand about the narratives you're studying? Your questions will guide whether you focus on content, structure, or context.

- Choose your analytic approach. Based on your questions, decide whether thematic, structural, or dialogical analysis (or a combination) best serves your goals.

- Collect your narrative data. Gather narratives (via interviews, document analysis, or other methods) that address your questions.

- Set up your analysis infrastructure. Organize your data in a way that supports systematic analysis. If working with substantial data, consider using MAXQDA to manage complexity and enhance rigor.

- Start small and build. Practice your analytic approach on one or two narratives to refine your methods before applying them to your full dataset.

- Join the conversation. Narrative analysis has rich traditions and active communities. Engage with methodological literature, attend workshops, and connect with other narrative researchers.

Narrative analysis offers a powerful way to understand how people make sense of their experiences and how stories shape lives and cultures. Whether you're examining patient illness narratives, organizational change stories, or social movement testimonies, this framework uncovers a deeper understanding that respects both individual stories and the patterns that connect them.

Approach narratives with rigor and openness: Be systematic to ensure trustworthy findings, but stay flexible so stories can surprise you. With clear methods, the right tools, and genuine curiosity, narrative analysis generates understanding that matters.

Ready to explore narrative analysis with real data? Try MAXQDA’s free demo to see how it supports each step of the process.

Frequently Asked Questions

References and Further Resources

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass.

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (2012). Approaching narrative analysis with 19 questions. In S. Delamont (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research in education (pp. 474–488). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. University of Chicago Press.

Franzosi, R. (1998). Narrative analysis—Or why (and how) sociologists should be interested in narrative. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 517–554. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.517

Georgakopoulou, A., & De Fina, A. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of narrative analysis. Wiley Blackwell.

Josselson, R., & Hammack, P. L. (2021). Essentials of narrative analysis. American Psychological Association.

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Rädiker, S., & Gizzi, M. C. (Eds.). (2024). The practice of qualitative data analysis: Research examples using MAXQDA, Volume 2. MAXQDA Press.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

Smith, B. (2016). Narrative analysis. In E. Lyons & A. Coyle (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data in psychology (2nd ed., pp. 202–221). SAGE.

About the author

Xan (he/him) recently completed a master’s degree in sociology at Freie Universität Berlin. He now works at VERBI Software as a product manager, working on product documentation and localization processes.