Last update: 29.01.2026

What Are Semi-Structured Interviews?

Semi-structured interviews are a flexible form of qualitative data collection that balances structure with openness (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). Unlike structured interviews, which follow a fixed script, semi-structured interviews are guided by a set of prepared questions but leave room for the interviewer to probe, follow up, or adapt based on the participant’s responses. This approach enables the generation of comparable data across participants while also capturing unique perspectives and stories. A central feature of this method is the interview guide, which is a checklist of questions or topics that ensures the same core issues are explored across participants while still allowing the interviewer freedom to adjust wording, explore emerging ideas, and maintain a conversational flow. Rather than dictating every question in order, the guide sets the overall direction and key topics to be covered, but leaves flexibility in how the interview unfolds (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). This balance makes semi-structured interviews both systematic and comprehensive while leaving space for the unexpected insights that often make qualitative research so valuable.

History & Development of Semi-Structured Interviews

The practice of interviewing has a long history, but semi-structured interviews have their roots in the expansion of qualitative research in the mid-20th century, which was also at the same time as the rise of survey research and opinion polling (Platt, 2001). However, during this time, researchers often relied on structured interviews, using fixed questions. This era emphasized standardization, interviewer control, and comparability across large numbers of respondents (Platt, 2001). While this brought efficiency, it also reduced interviews to instruments of data extraction, leaving little room for participants’ voices to shape the inquiry.

By the 1960s and 1970s, researchers began to criticize the rigidity of structured interviews. Thus, qualitative research expanded to include many types of interviews, such as oral histories and life history interviews. Specifically in anthropology, unstructured interviewing, which allowed for free-flowing discussion, had already been used to document the lives of small, often non-Western societies (Spradley, 2016). By the 1970s, interviewing had become central to ethnographic fieldwork, and subsequently, ethnographic interviewing had moved beyond anthropology into other fields. Consequently, interviewing was reimagined as a way not only to collect information but also to learn directly from participants about cultural meanings and lived experience (Spradley, 2016).

Out of this trajectory, the semi-structured interview emerged, which is structured enough to ensure that key topics are consistently addressed across participants, but flexible enough to let participants shape the flow of discussion (Brinkmann, 2020). In other words, the semi-structured interview guide will act as a roadmap rather than a script, ensuring that limited time is used efficiently while leaving space for exploration. By the late 20th century and still today, semi-structured interviewing has become one of the most widely used qualitative data collection strategies in social science research (McIntosh & Morse, 2015). Nowadays, with the prevalence of digital tools, researchers can record, transcribe, and analyze semi-structured interviews with ease.

In Relation to Other Types of Interviews

Interviews can take many forms depending on the research question, setting, and qualitative approach. The most general way to distinguish between them is by degree of structure:

- Structured Interviews: Fixed questions asked in the same order for every participant. Useful for producing consistent, comparable data, but limited in depth.

- Unstructured Interviews: Conversational and exploratory, resembling an informal dialogue. The interview questions are generated based on the interaction with the participant in the interview; therefore, allowing them to mainly direct the conversation.

- Semi-Structured Interviews: Guided by a flexible set of questions but adaptable to each discussion with the participant, with the use of probes and follow-up questions. They balance consistency across interviews with a focus on the research topics of interest, with openness to unanticipated insights.

However, not all interview types are best understood along this structured–unstructured continuum. For example, other types of interviews are life history interviews to capture a participant’s biographical trajectory (Kim, 2015) and ethnographic interviews to support participant observation and the study of a culture (Spradley, 2016). Yet, in this broader landscape, semi-structured interviews remain a particularly versatile approach since they provide structure to ensure comparability while retaining flexibility to explore the richness and diversity of human experience.

Why Use Semi-Structured Interviews?

Strengths for Qualitative Research

Semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research because they offer a unique balance of structure and flexibility (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Patton, 2015). Unlike fully structured interviews, which may limit responses to narrowly framed questions, semi-structured interviews provide space for participants to express their perspectives in their own words using spontaneous questions that arise from the discussion. This allows researchers to uncover meanings and experiences that might not emerge in a standardized format. Also, semi-structured interviews encourage rapport-building, as the conversational style tends to feel more natural and less interrogative than that of structured interviews. This can lead participants to share more openly, producing richer and more authentic data. While unstructured interviews can be great to use in the initial stages of a project to explore the research questions, usually, there will be key topics, events, experiences, or concepts that researchers are keen on knowing about, so the degree of structure in semi-structured interviews will succeed in being able to get at those interests. Moreover, this use of an interview guide ensures that essential elements are consistently covered across participants, while still leaving room for depth and nuance (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Patton, 2015).

Common Applications

Because of these strengths, semi-structured interviews are used in a wide range of disciplines and applied settings, such as:

- Academic Research: In education, psychology, sociology, anthropology, public health, and several more academic fields, semi-structured interviews help researchers explore complex phenomena. For instance, Chang et al. (2013) used semi-structured interviews to study prenatal care providers’ perspectives on weight gain during pregnancy and Oomen-Welke et al. (2023) interviewed highly sensitive persons after forest vs. field exposure to capture their subjective experiences.

- Human Resources: Semi-structured interviews can be part of recruitment processes and employee engagement assessments as they allow HR professionals to maintain consistency for evaluating employees and their workplaces but adapt questions to the individuals being interviewed.

- Market and User Experience Research: Businesses use them to explore consumer attitudes, preferences, and decision-making. In UX and user research, semi-structured interviews can be used during discovery phases to uncover emotional motivations beyond usability or to understand how people interact with products and services (Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF, 2017).

- Program Evaluation: Semi-structured interviews are especially valuable in program evaluation when evaluators need to explore implementation processes, stakeholder experiences, or areas for improvement. These interviews are well suited for formative evaluations that require one-on-one interviews with key program managers or staff (Adams, 2015). They are also effective for conducting in-depth investigation before large-scale surveys, clarifying issues that emerge from quantitative findings, and capturing the perspectives of program recipients, interested stakeholders, and administrators. Furthermore, their flexibility allows evaluators to follow leads, probe for explanations, and gain nuanced understanding of how a program operates in practice (Adams, 2015).

- Business Strategy & Organizational Change: In the context of strategic decision-making and organizational changes, semi-structured interviews can capture executives’, managers’, or employees’ reasoning, beliefs, and experiences behind strategic shifts. For example, a study of 16 employees in an R&D project used semi-structured interviews at different project stages to explore perceptions of complexity and funding dynamics (González-Varona et al., 2023).

- Design and Innovation Research: Semi-structured interviews can be beneficial during innovation and design phases to surface stakeholders’ values, organizational needs, or emergent strategic insights. For example, (González-Varona et al., 2021) used six semi-structured interviews with academic and industry experts to refine a model of organizational competence for digital transformation, demonstrating how this method supports early-stage design strategy and innovation management.

- Environmental Management: Semi-structured interviews can also play an important role in environmental management and policy analysis, particularly in developing or refining management strategy evaluation (MSE) frameworks. Damiano et al. (2022) showed how interviews with fishers and other stakeholders were integrated into a fisheries MSE process to identify key social, economic, and institutional drivers. The approach revealed stakeholder values and perceptions that quantitative models alone could not capture, strengthening environmental strategy by integrating human dimensions of decision-making and promoting more credible, stakeholder-informed management outcomes.

As shown across these applications, semi-structured interviews can work well in research, where new ideas might need to be uncovered, and applied settings, where decisions must be informed by the voices of various stakeholders.

Designing Semi-Structured Interviews

Crafting Questions

The foundation for a strong semi-structured interview is a carefully prepared interview guide. This is not a script but a flexible checklist of topics and questions to be covered. A good guide ensures that the same broad and critical issues are explored across participants while leaving room for variation in how those issues are addressed by the participants. In this guide are obviously going to be questions, but before creating them, the interviewer must consider the many types of questions that can be asked. One simple way to classify them is easy vs. hard questions, where the former are topics that are comfortable and easy to answer, but still connected to the research, and the latter are topics that can be more sensitive or difficult to answer (Patton, 2015). A more detailed classification comes from Patton (2015), where there are six types of questions: Experience and Behavior, Opinion and Values, Feeling, Knowledge, Sensory, and Background.

Whatever type of questions are used, the more important piece is how to order them in the interview guide so that the interview flows well while still attending to all the pieces the interviewer is interested in discovering from the interview. A general recommendation for the order is to begin with broad, open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me about your experience with…”) before moving to more specific questions. This beginning should be easy for the participants so that they are able to build confidence and familiarity with the overall topic before moving on to more specific and difficult parts. Additionally, this beginning will help to build rapport between the interviewer and interviewee. Whether it is an easy or hard question or in whatever place it comes in the guide, the interviewer must also anticipate areas where they may want to follow up (e.g., “Can you give me an example?” or “How did that make you feel?”). These follow-ups are key to the “semi” piece of the guide.

Ethical Considerations

Designing a semi-structured interview also involves careful attention to ethics. Because these interviews often deal with personal experiences, researchers have a responsibility to protect participants’ well-being and ensure integrity in data collection. Key considerations include:

- Informed consent: Participants must understand the purpose of the study, what participation involves, and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Confidentiality: Sensitive information should be anonymized, and interview recordings or transcripts must be securely stored.

- Respect and sensitivity: Interviewers should be prepared for emotional topics and have strategies to respond appropriately if participants become distressed.

- Power dynamics: Especially in professional, healthcare, or cross-cultural contexts, the interviewer should be mindful of imbalances that could shape what participants feel comfortable sharing.

- Transparency: Researchers should avoid overpromising outcomes and make clear how participants’ data will be used.

By designing interviews with ethics in mind, researchers build trust with participants and strengthen the credibility of their study.

An Example of a Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Here’s a sample one-page semi-structured interview guide you could adapt for your purpose.

Study Topic: Exploring participants’ experiences with [insert program, service, or phenomenon]

Purpose: To understand participants’ perspectives, motivations, and challenges related to their involvement in [topic].

[Ensure that consent is given, participant understands the interview’s purpose, and that they can ask any questions before the interview starts.]

Opening / Rapport-Building

- “Tell me about your connection to [topic/program]”

- Probes if needed: “How did you first get involved?” “What drew you to participate?”

Core Questions

- “Describe your experience with [topic/program] so far.”

- Probes if needed: “What stands out most to you?”

- “What have been the most valuable aspects of your experience?”

- “Have you faced any challenges?”

- Probes if needed: “What made those challenges difficult?” “How did you respond?”

- “In what ways has [topic/program] influenced your daily life?”

- Probes if needed: “How do you think it compares to your expectations?”

Suggestions

- “If you could make one change to improve [topic/program], what would it be?”

- Probes if needed: “How would it help others like you?”

Closing

- “Is there anything else you’d like to share about your experience that I didn’t ask?”

[End by thanking participants, asking if they’d like to add anything, and clarifying what happens next with their data.]

Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews

Preparation & Setup

Careful preparation will help semi-structured interviews run smoothly and generate meaningful data. Some, but not all, steps for preparation include:

- Review your list of questions and probes, ensuring they are clear, open-ended, and aligned with your research questions. The interview guide can be slightly refined as data is collected and analyzed

- Conduct one or two trial interviews to check if the questions flow naturally and yield the type of information you need.

- Schedule interviews at times and locations that are comfortable and accessible for participants. If in person, confirm that the location is accessible for the participant and that the space is conducive to having the interview, meaning audio and video (if used) will be able to be recorded, and that there is enough privacy. If remote (e.g., Zoom, Teams), confirm that the participant has a stable internet connection, the necessary equipment for audio and video (if used), and that they do it somewhere in private.

- Choose a quiet, distraction-free space where confidentiality can be maintained. This applies to the interviewer and interviewee.

Best Practices During the Interview

Semi-structured interviews should feel like guided conversations. How to achieve this will depend on the participant. For example, some participants are naturally talkative, while others will be shyer for different reasons. Therefore, consider this list as general best practices:

- Begin with small talk or broad, non-threatening questions to help participants feel at ease.

- Show attentiveness through eye contact and verbal and non-verbal affirmations (when appropriate), but without interrupting the participant.

- Encourage participants to elaborate rather than give yes/no answers by asking open-ended questions. For example, asking “What do you like about the program?” instead of “Do you like the program?”

- Be willing to adjust the order of questions and explore unanticipated but relevant topics based on the direction the participant takes you with their answers.

- If a participant gives a short answer that is not too informative, use follow-up probes (e.g., “Tell me more about [topic]”) to deepen responses.

- Avoid showing approval or disapproval of participants’ answers so that you do not lead them to just give you answers that they think will obtain your approval.

- Keep the interview within the promised timeframe while ensuring all key topics are covered.

Recording & Notetaking

Capturing the interview accurately is crucial. Most of the time, interviewers will rely on audio or video recordings, made with the participant’s consent, to preserve the conversation. However, a backup recording device is always wise, since technology can fail. Alongside recordings, interviewers often keep brief notes during the session, jotting down key words, time stamps, or, if relevant, observations about tone and body language. These notes are not meant to capture every word but to supplement the recording and provide context that may not be audible later. Additionally, having the interview questions jotted down can assist in navigating the interview since one can note where to pivot across the planned guide. Immediately after the interview, expanding these notes while memories are fresh helps preserve important impressions. The combination of recordings and notes ensures that the participant’s voice is truthfully represented. Finally, all material, including recordings and notes, must be stored securely to uphold confidentiality. If the material is digital, store it in a folder on a password-protected computer. If this material is not digital, store it somewhere where only approved people on the project can access.

Challenges and How to Address Them

Managing Interviewer Bias

A challenge in semi-structured interviewing (and across all types of interviews) is the risk of biasing interviews. There is always the possibility that the interviewer’s assumptions, expectations, or interpretations might shape the questions asked or the way responses are heard. For instance, subtle cues such as nodding in agreement or paraphrasing a participant’s response can unintentionally signal approval or disapproval. To minimize this, interviewers should engage in reflexivity: regularly reflecting on their positionality and how it might influence the conversation. Using neutral wording, resisting the urge to share personal opinions, and keeping a journal of reflections after each interview are practical strategies for maintaining awareness and reducing bias. Having trials of the interview also helps interviewers recognize and manage unconscious tendencies that may creep into the interaction.

It is equally important to avoid phrasing that can make participants feel judged or pressured. For example, “why” questions can sometimes come across as accusatory, prompting defensiveness rather than reflection. A better approach is to reframe such inquiries into descriptive statements. For instance, instead of asking, “Why did you do that?” an interviewer might say, “Walk me through what led up to that decision.” This encourages deeper storytelling without making the participant feel on trial.

Keeping Interviews on Track

Semi-structured interviews are designed to be flexible, but this very flexibility can lead to digressions or conversations that drift too far from the research focus. Participants may wander into lengthy stories, or the interviewer may get drawn into side discussions. While these detours sometimes produce valuable insights, interviewers need strategies to balance openness with focus. Gentle redirection can be effective. Phrases such as “That’s really interesting because returning to your earlier point about…?” acknowledge the participant’s contribution while steering the conversation back to the key topic.

Time management is equally important. Not all questions need to be asked in detail if the participant has already addressed them indirectly. The interviewer’s skill lies in knowing when to probe further and when to move forward, which is why notetaking for this purpose can benefit the interviewer. For example, if a question is answered early in the interview, you can cross it out or make a note of that to remind you.

Avoiding certain types of questions also supports focus. Leading questions (e.g., “Don’t you think this program was helpful?”) can bias responses, while double-barreled questions (asking about two issues at once) may confuse participants or produce incomplete answers. Keeping questions simple, clear, and neutral makes it easier to maintain direction and consistency across interviews. Additionally, again concerning “why” questions, they presuppose that the participant can determine the cause and effect for the thing in question. This can sometimes be too tough a question since it moves beyond what the participant experiences or feels and thus causes the participant to be flustered and negatively affects the interview’s flow.

Building Rapport & Navigating Power Dynamics

Successful interviews depend on trust and rapport, yet building this relationship can be complicated by differences in age, gender, race, professional status, cultural background, and more. These differences can create power imbalances that shape what participants are willing to share. To navigate this, interviewers must be intentional in establishing respect and empathy from the outset. Starting with small talk, explaining the purpose of the study clearly, and showing genuine curiosity about participants’ experiences can all help put them at ease. Active listening and nonjudgmental responses further reinforce rapport. At the same time, researchers should remain mindful of power dynamics: for example, a student interviewing a teacher may need to acknowledge the authority gap, while a healthcare professional interviewing patients must be sensitive to the vulnerability participants may feel. Being transparent about confidentiality, emphasizing participants’ right to decline any question, and practicing humility go a long way toward balancing these dynamics. Ultimately, rapport and ethical mindfulness create a space where participants feel both respected and safe to share their perspectives.

When rapport is fragile, certain question styles can make matters worse. Overly formal or abstract questions at the start of an interview may intimidate participants, while emotionally charged or judgmental wording can shut down disclosure. Beginning with accessible, open-ended questions and gradually working toward more sensitive issues helps establish trust and minimizes the risk of reinforcing power imbalances.

Analyzing Semi-Structured Interviews with MAXQDA

Transcription & Data Preparation

The first step in analyzing semi-structured interviews is ensuring that the data is properly prepared. With MAXQDA, researchers can transcribe directly within the software, using tools that allow them to slow down audio, easily navigate recordings, and make a wide range of edits to the transcription, ready for further analysis. There are two options for transcribing with MAXQDA: Automatic Transcription and Manual Transcription.

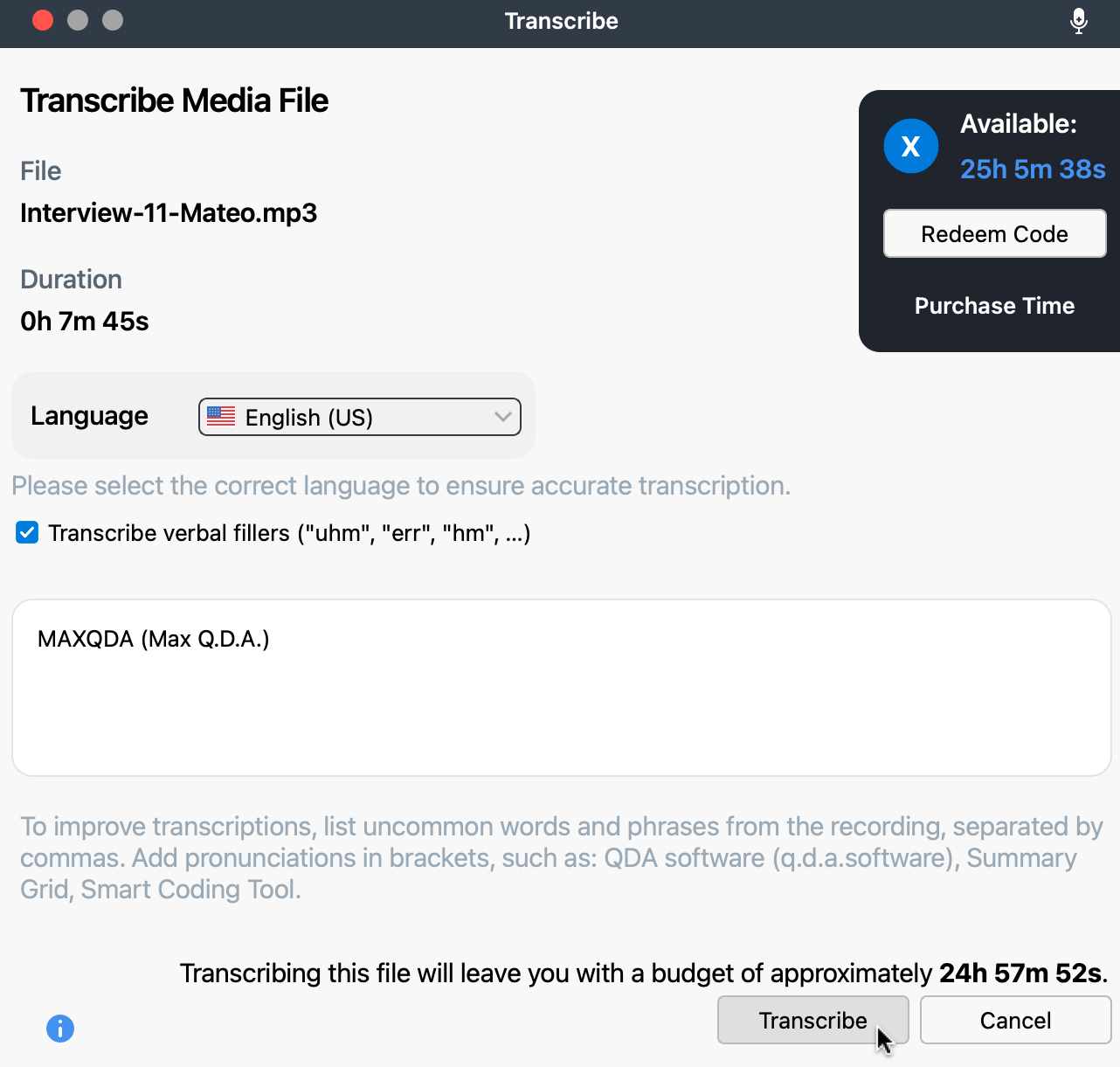

With Automatic Transcription, MAXQDA’s AI-powered service saves you valuable time by generating a transcript of your audio or video recordings within minutes (Figure 1). All you need is a MAXQDA account and the Transcription add-on. The system supports over 50 languages, automatically adds punctuation, and inserts timestamps that link directly to the corresponding sections of the recording. This means you can easily jump back to specific parts of the interview to check accuracy or context. Once the automatic transcript is created, you can review and edit it to ensure precision and prepare the text for coding and further analysis. For example, perhaps it will be useful to format the semi-structured interview questions so that the analyst(s) can easily see what prompted participant responses.

Here’s a general step‑by‑step guide to creating an automatic transcription in MAXQDA:

- Create or sign in to your MAXQDA Account (New users receive 60 free transcription minutes to test the service.)

- Activate Transcription

- Make sure the Transcription add‑on is enabled.

- You can activate it during purchase or later in your MAXQDA Account.

- Import Your Media File

- In MAXQDA, go to the Import tab and select “Audio” or “Video.”

- Choose your file or simply drag and drop it into the software.

- Alternatively, if the file is already imported, right‑click it and select Transcribe Audio File > Transcribe Automatically with MAXQDA Transcription.

- Configure Transcription Settings

- Choose the recording’s language from over 50 available options.

- Add custom vocabulary or glossary terms (useful for technical terms, names, or jargon).

- View your remaining transcription budget in the settings dialog.

- Start the Transcription

- Click Start Transcription.

- The process will run in the background while you continue working in MAXQDA.

- Check the transcription status in the interface until it turns to Done.

- Review and Edit the Transcript

- The finished transcript is automatically imported into your MAXQDA project.

- Open it from the Document System or the notifications panel.

- Edit the transcript for corrections, add speaker labels, or adjust formatting.

- Use timestamps to replay specific parts of the audio/video for verification.

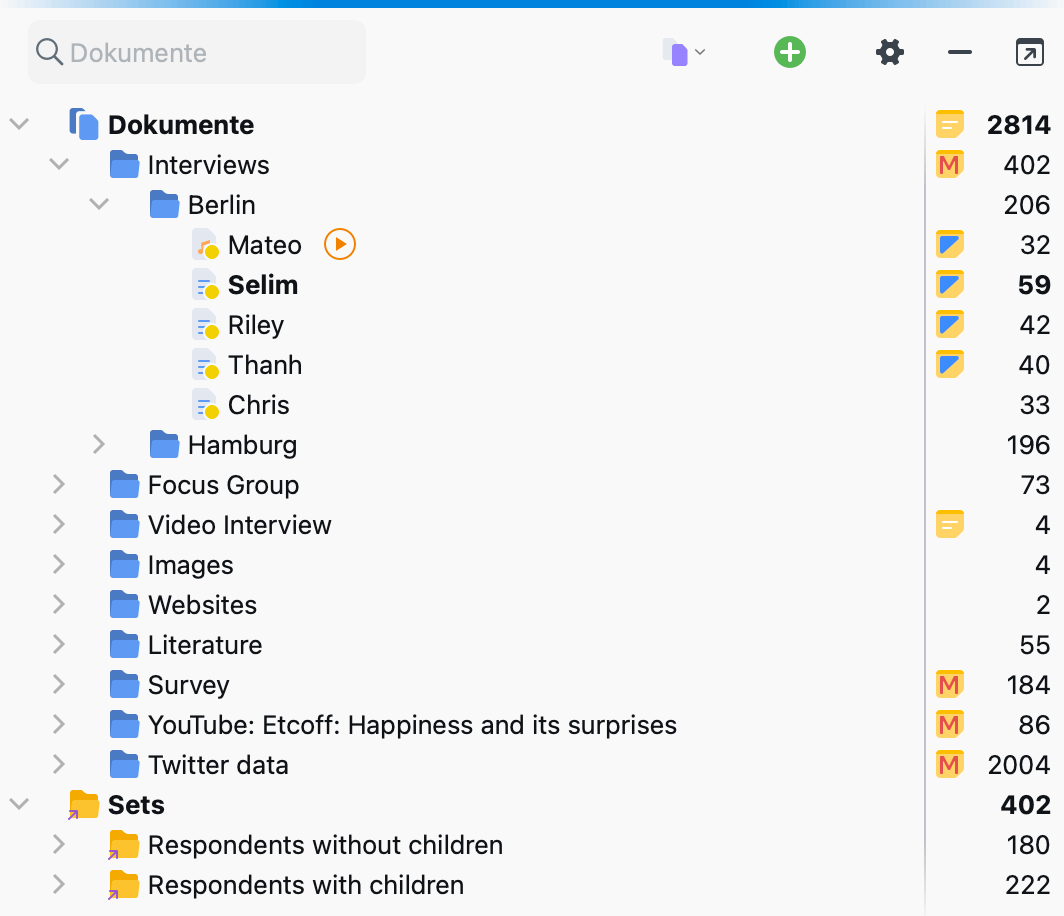

If you work with existing transcripts, MAXQDA supports importing a wide range of file types. Once transcripts are imported, they can be aligned with their corresponding audio or video files, enabling synchronized playback while reading text. This makes it easier to revisit tone, emphasis, and pauses that might add meaning beyond the words alone. Preparing your transcripts in MAXQDA also means you can begin organizing them immediately by assigning document groups (Figure 2), adding variables (e.g., participant demographics), or attaching memos to capture initial thoughts.

Familiarization

Before diving into coding, it is important to spend time getting to know your semi-structured interview transcripts. MAXQDA supports this process by providing tools for memoing and annotation. Researchers can write document memos to summarize the main themes of an interview or insert in-text memos at specific passages to record emerging insights. Familiarization is also enhanced by re-reading transcripts while listening to the original audio, allowing you to pick up subtle cues such as emotion or hesitation that may not be fully captured in text.

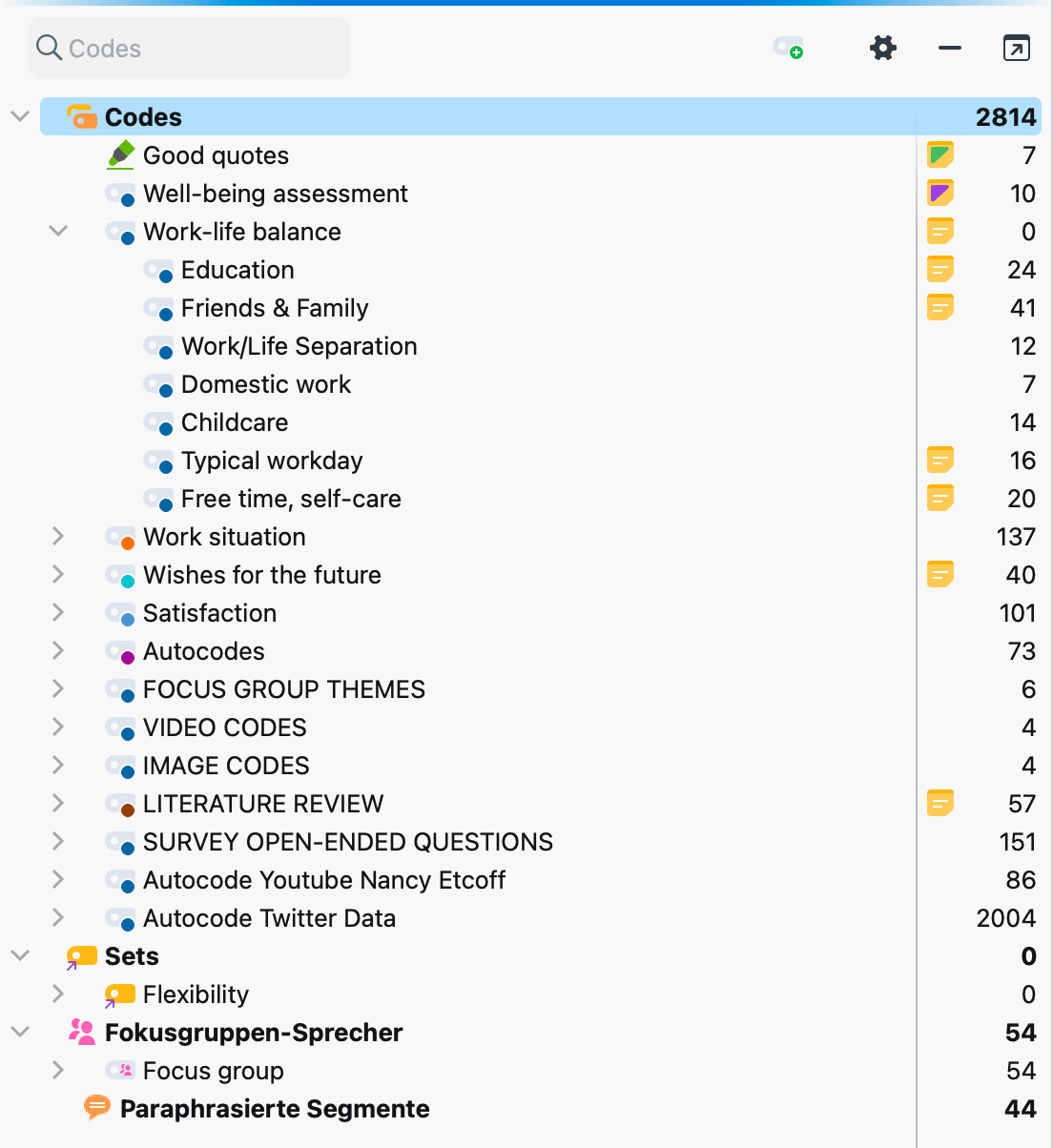

Coding

Coding is most of the time the core of qualitative analysis, and MAXQDA is designed to make this process efficient and flexible. Codes can be created inductively (emerging from the data) or deductively (based on theory, interview questions, etc.), and MAXQDA allows you to apply them directly to text, audio, or video segments. You can build a coding system hierarchically, starting with broad categories and gradually refining them into subcodes (Figure 3). Because semi-structured interviews combine consistent questions with emergent narratives, your code system may reflect both question-driven categories and participant-led insights.

In the case of semi-structured interviews, this flexibility is especially valuable because the data set typically combines guided responses to your interview questions with spontaneous, participant-driven narratives. You can begin with a deductive framework drawn from your interview guide to ensure that core research questions are covered, while simultaneously adding inductive codes whenever new themes emerge. To do this in MAXQDA, highlight any meaningful passage and drag a code from the Code System onto the text, or create a new code on the spot using the Open Coding function.

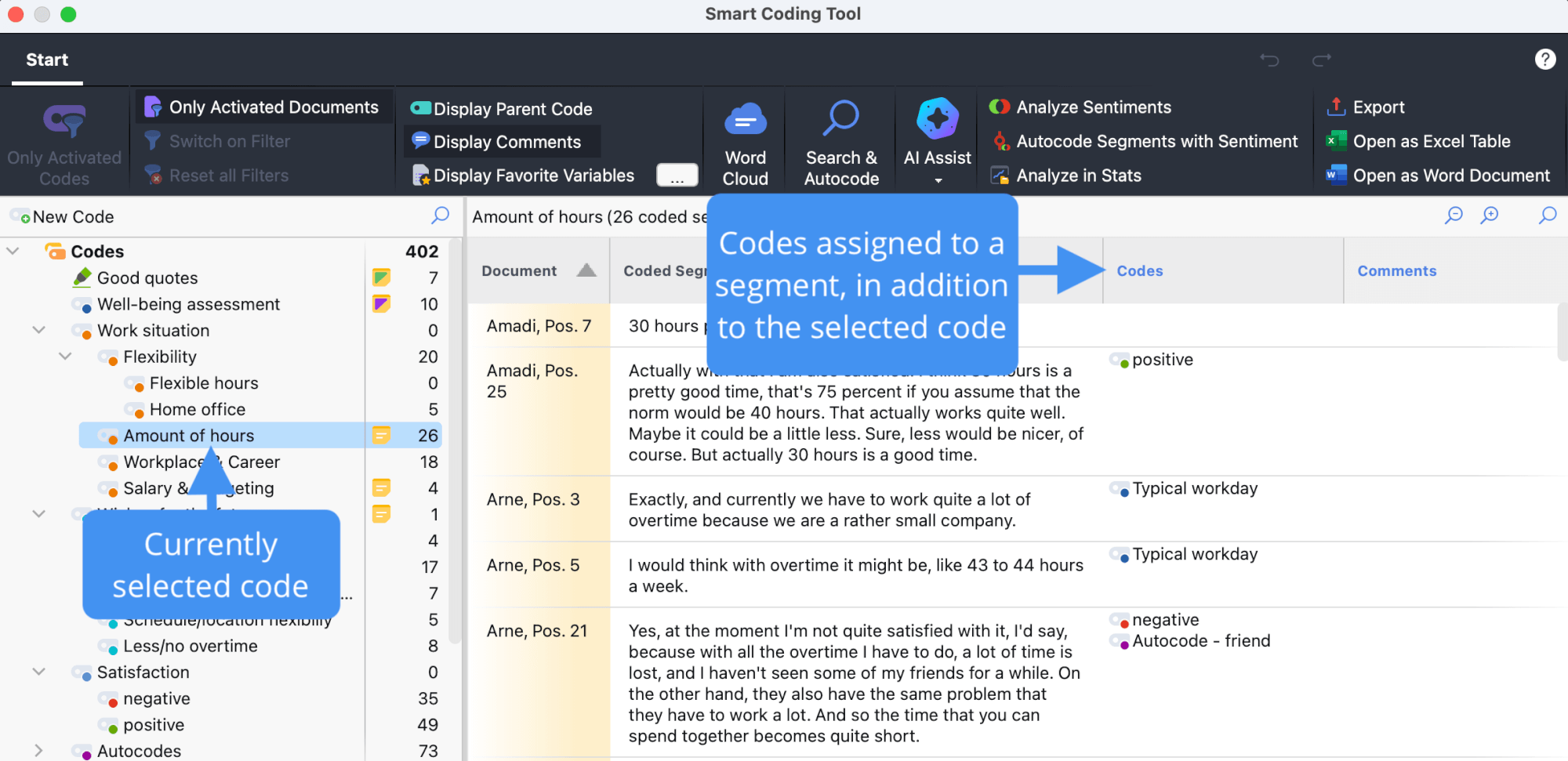

Over time, your coding system will evolve into a clearly structured hierarchy. For example, an initial code like Workplace Challenges can then be subdivided into more specific subcodes such as Workload, Management Style, and Collaboration. MAXQDA’s Creative Coding and Smart Coding tools make this refinement easier by allowing you to visually reorganize, merge, or break down codes into subcategories while keeping the overall structure transparent (Figure 4).

From Analyzing to Reporting

Visualizing Findings

Visualizations play an important role in bridging the step from detailed analysis to clear and engaging reporting. For semi-structured interview projects, MAXQDA offers a variety of tools that allow you to not only illustrate results for your audience but also to gain deeper insights during the analysis process itself. By strategically selecting visualizations that match your research questions, you ensure that your final report not only conveys results but also demonstrates how interpretations are grounded in the data.

There are a lot of visual tools in MAXQDA, but here are a few ways you can use them for reporting the results of your analysis:

- Use visualizations as both analytical and presentation tools

Visual tools such as code maps, document portraits, or frequency charts can highlight relationships, trends, and contrasts within interview data.

- Visualize codes, themes, and relationships

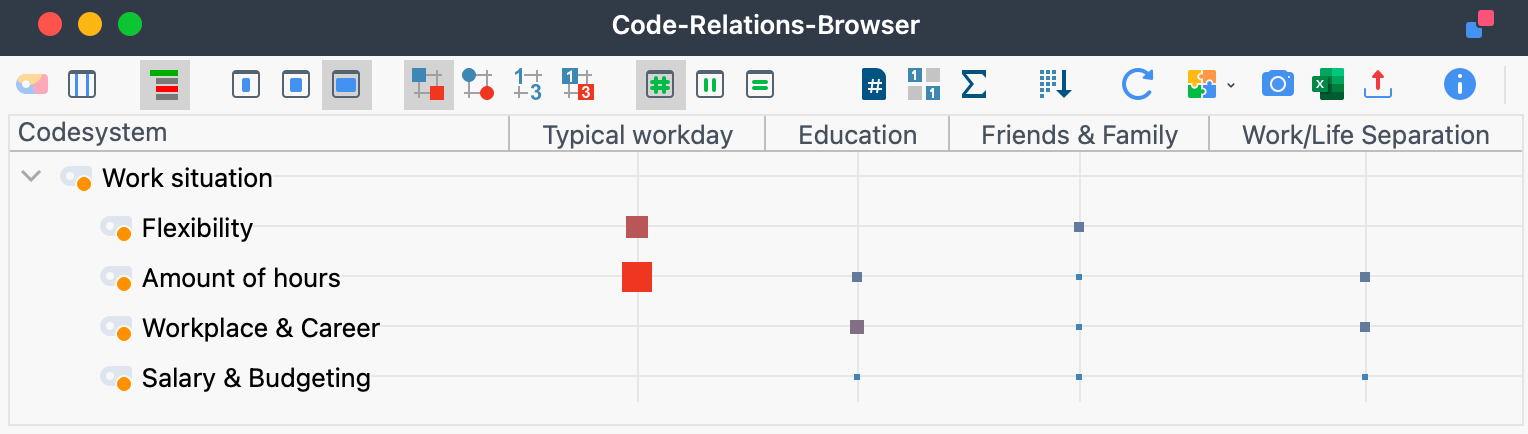

The code relations browser (Figure 5) and MAXMaps allow you to represent how codes and themes interconnect, how often concepts were mentioned, or how perspectives differ across cases. For semi-structured interviews, this makes it easier to display variations between participants while keeping findings linked to the underlying coded material.

- Integrate linguistic aspects

In some projects, analyzing words or phrasing choices is particularly relevant. Word frequency clouds, keyword-in-context visualizations, and word matrices can add to your analysis by illustrating patterns in how ideas are expressed through a linguistic lens.

Using the Question-Themes-Theories Workspace

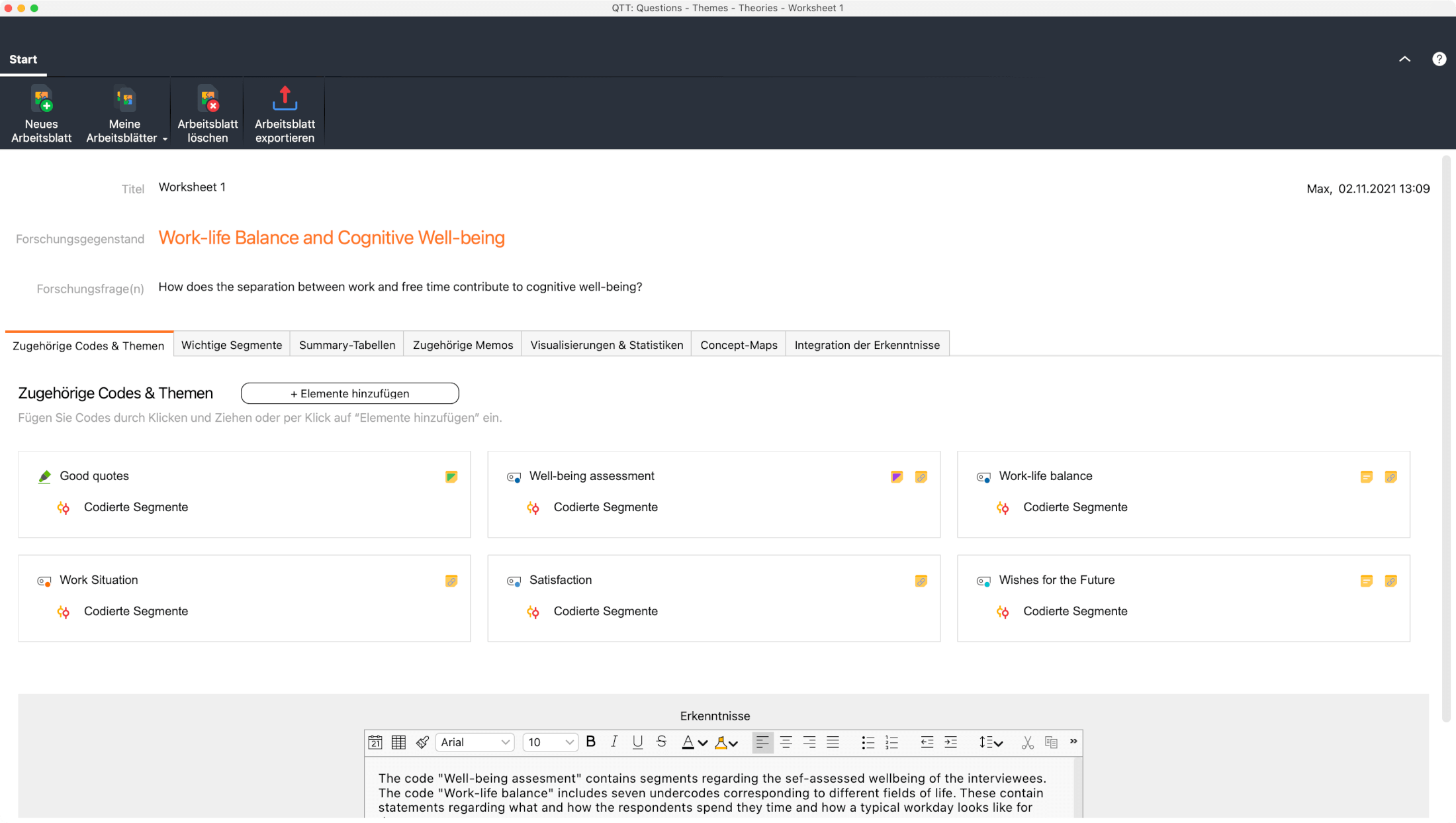

The Questions–Themes–Theories (QTT) Workspace provides a structured environment to move from coded data toward interpretation and reporting (Figure 6). In the context of semi-structured interviews, QTT acts as a central hub where your research questions, key themes, and insights come together.

A summary of how to use the QTT workspace is the following:

- Create a dedicated worksheet

Open the QTT Workspace through the Analysis > QTT: Questions–Themes–Theories menu and create a new worksheet for each of your main topics or research questions. Each worksheet automatically contains sections such as Related Codes & Themes, Important Segments, Memos, Visuals & Statistics, Concept Maps, and an Integration of Insights area (Figure 8).

- Bring analysis elements together

Populate the worksheet by adding codes, significant coded segments, related memos, and visualizations from your MAXQDA project. You can also include concept maps and summary tables to represent connections between categories or participants’ perspectives. These elements stay linked to your original interview data, ensuring transparency.

- Document insights and interpretations

For each element you add, you can record analytical notes or conclusions. These reflections are automatically compiled into the Integration of Insights section, which serves as a running synthesis of your findings. This feature makes it easier to see how raw interview data supports broader themes or theories.

- Prepare for reporting

The QTT Workspace provides a direct bridge between data analysis and the writing of your report. You can export individual sections or entire worksheets as Word documents, making it simple to transfer your synthesized findings into chapters, literature reviews, or other sections in a manuscript or report.

Writing About Findings

The QTT Workspace functions as both an analytical and writing scaffold. As you synthesize your coded data in QTT, you simultaneously construct the foundation of your research report—connecting your interview questions, emerging themes, and theoretical interpretations. Each worksheet operates as a dynamic outline where you compile supporting evidence, summarize analytical insights, and record interpretive reflections.

When you begin writing about your findings, this preparatory work naturally evolves into narrative form. The summaries, memos, and visual materials developed in QTT can be transformed into cohesive paragraphs that explain how specific interview excerpts exemplify key themes. Because many QTT elements are linked to the original data, quotations and examples can be easily retrieved from your semi-structured interviews. In this way, writing becomes a natural continuation of your analytic process rather than a separate phase—your narrative extends and articulates the conceptual structure already organized within the QTT Workspace.

Exporting Your Work

Once your analysis and writing in the QTT Workspace are complete, MAXQDA offers several ways to export your results for reporting, collaboration, or archiving. Exporting ensures that your analytic insights, coded data, and visualizations can be integrated directly into your final research report or shared with others who may not have access to MAXQDA.

- Exporting from the QTT Workspace

You can export individual worksheets or complete QTT projects to Word or Excel files with a single click. This allows you to preserve the structure of your analytic summaries— including categories, codes, and supporting quotations—exactly as they appear in QTT. In Word, exported worksheets serve as ready‑to‑edit sections of your report; in Excel, they provide a compact overview of your coded themes and summaries for further data synthesis.

- Exporting Coded Data and Codebooks

For documentation or team collaboration, you may also export coded text segments, summaries, and your code system—including code memos and definitions. This export provides transparency in your analytic process and enables others to review or reuse your coding framework in future research.

- Including Visualizations and Tables

If your analysis includes visual components—such as concept maps, code matrices, or summary tables—these too can be exported as images or embedded objects. Visuals generated in MAXQDA can help illustrate relationships between themes, participant groups, or theoretical constructs in your written report.

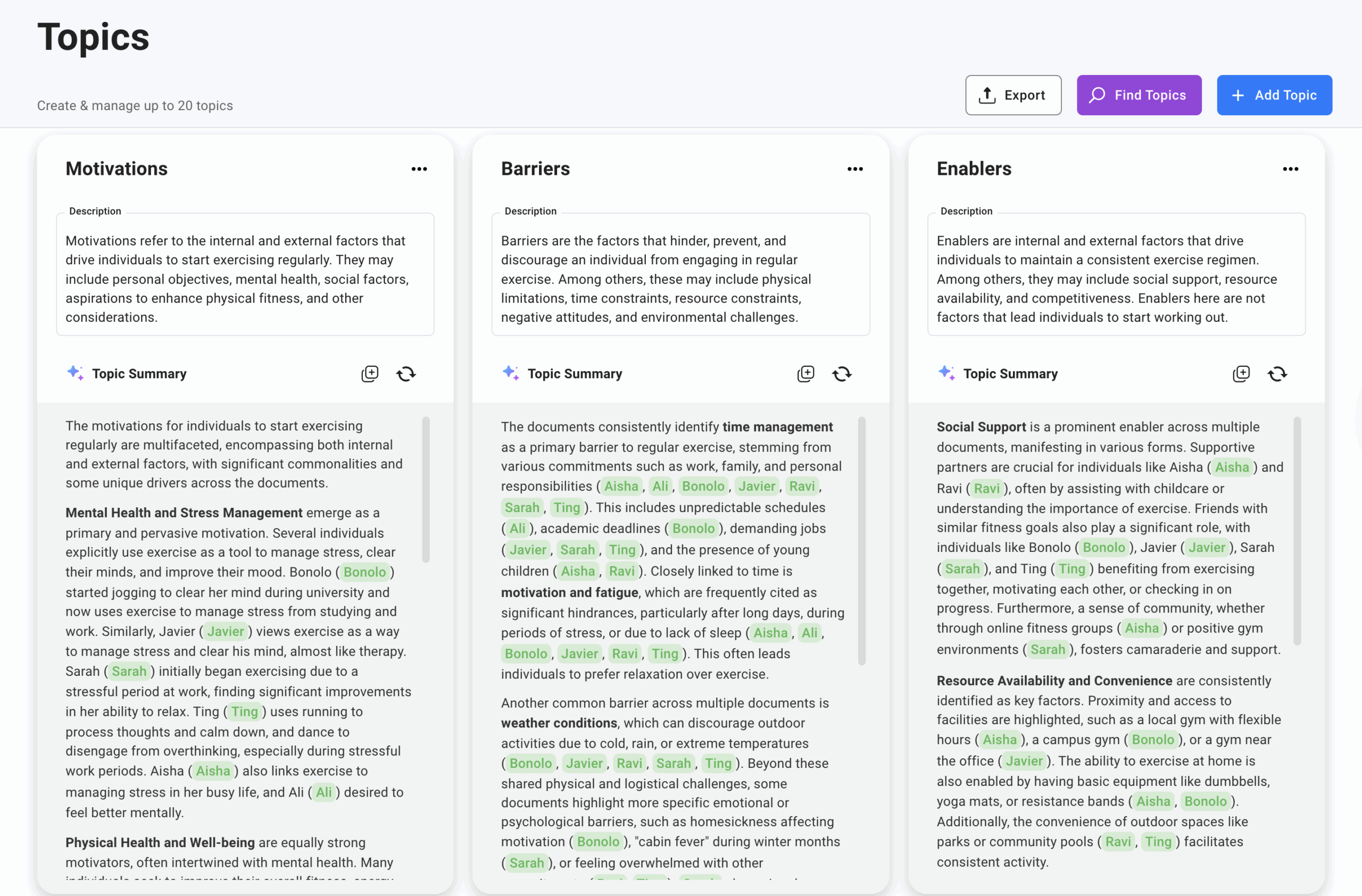

MAXQDA Tailwind

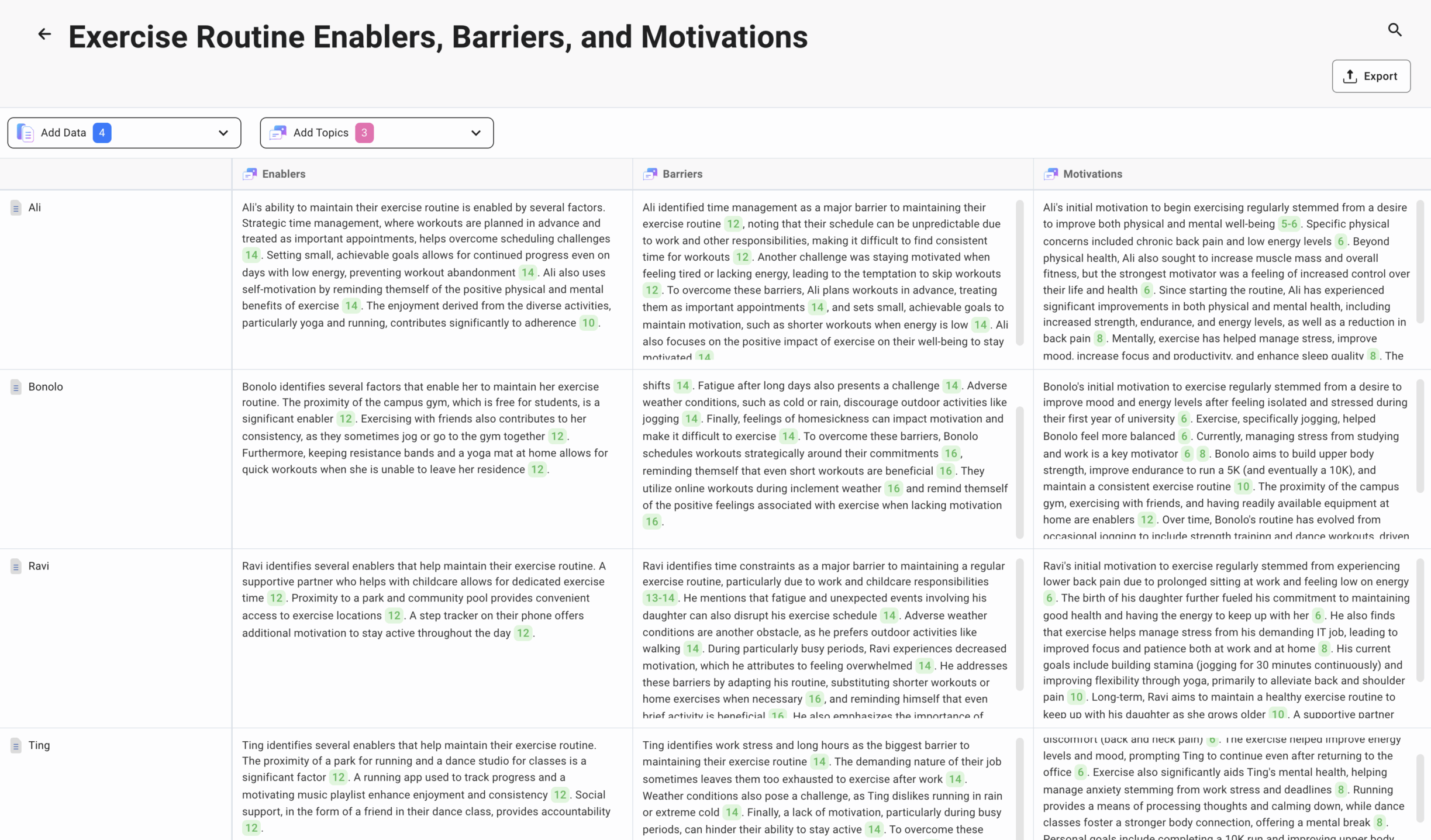

MAXQDA Tailwind can also support your analysis of semi-structured interviews by generating AI-driven summaries of your documents, highlighting topics, and answering questions directly about the content through its AI Chat. Once you upload your transcripts, Tailwind automatically produces document summaries that are linked back to their original passages, so you can quickly orient yourself while maintaining full transparency. From there, you can use the Topics Dashboard to either let Tailwind suggest potential topics with the Find Topics feature or create topics manually that reflect ideas you already see emerging in the data (Figure 7). Each topic is displayed as a tile with a name, description, and an AI-generated summary that you can refresh or refine as your project evolves.

If you want to compare perspectives, the Summary Tables function is especially useful (Figure 8): you select specific documents and topics, and Tailwind fills the cells with concise AI-written overviews, making it easy to see how issues are discussed across interviews, focus groups, or reports. At any point, you can deepen your exploration with the AI Chat feature. Here, you select the documents you want to analyze, type a question such as “What do participants say about teamwork?”, and Tailwind provides a synthesized response with interactive references that link back to the exact statements. This means you can move quickly from big-picture insights back to the raw data whenever necessary.

Together, these tools guide you through a structured but flexible analysis: you gain summaries to capture broad topics that can further structure your analysis, and chat-based queries to examine emerging interpretations. By combining these features, you can create a strong foundation before moving on to coding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

References and Further Resources

Adams, W. C. (2015). Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation (pp. 492–505). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119171386.ch19

Brinkmann, S. (2020). Unstructured and Semistructured Interviewing. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190847388.013.22

Chang, T., Llanes, M., Gold, K. J., & Fetters, M. D. (2013). Perspectives about and approaches to weight gain in pregnancy: A qualitative study of physicians and nurse midwives. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-47

Damiano, M., Wager, B., Rocco, A., Shertzer, K. W., Murray, G. D., & Cao, J. (2022). Integrating information from semi-structured interviews into management strategy evaluation: A case study for Southeast United States marine fisheries. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.1063260

González-Varona, J. M., López-Paredes, A., Poza, D., & Acebes, F. (2021). Building and development of an organizational competence for digital transformation in SMEs. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 14(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.3279

González-Varona, J. M., Martín-Cruz, N., Acebes, F., & Pajares, J. (2023). How public funding affects complexity in R&D projects. An analysis of team project perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 158, 113672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113672

Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. (2017, December 13). Semi-Structured Interviews. Interaction Design Foundation - IxDF. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/semi-structured-interviews

Kim, J.-H. (2015). Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research (1st edition). SAGE Publications, Inc.

McIntosh, M. J., & Morse, J. M. (2015). Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 2333393615597674. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (4th edition). John Wiley & Sons.

Oomen-Welke, K., Hilbich, T., Schlachter, E., Müller, A., Anton, A., & Huber, R. (2023). Spending time in the forest or the field: Qualitative semi-structured interviews in a randomized controlled cross-over trial with highly sensitive persons. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1207627

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Platt, J. (2001). The History of the Interview. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of Interview Research (pp. 33–54). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412973588

Spradley, J. P. (2016). The Ethnographic Interview. Waveland Press, Inc.