Guest post by Olena Zinenko.

Cultural public events are a popular subject of journalistic reflection but they are not well researched as a mass communication phenomenon. The most intriguing thing about public events is that they are not true facts of reality; instead, they are better described as “pseudo-events”, a phrase coined by Daniel Boorstin. They are socio-cultural interactions created by the agents of culture, the public, and the media.

Researching the Representation of Public Event Messages in Media

Perceptions of cultural public events in the mass-media are mostly based on the stereotype that they are just entertainment. But if we understand this phenomenon in an aesthetic way only, we lose a large scope of meaning about society and its interaction with mass-media.

The communicative potential of a public event is determined by the possibility of opening up new discourses in the media. In terms of mass communication theory, a public event is a complex message created and presented by the organizers in a specific context in order to attract the attention of the public and the media. The construction of the message of a public event is realized through symbolic performative codes that have both a direct and metaphorical meaning.

These can be local actions, such as setting the record for growing the largest pumpkin on Harvest Day, as well as cultural events on a global scale, such as the Eurovision Song Contest. The more diverse and wide the discourse of a public event in the media is, the more successful it is.

The rapid development of information society requires attention not only to the formulation of knowledge but also to the possibilities of its representation. By analyzing cases of public events, I deal with unstructured data, unpredictable reactions in mass-media, and the spread of comments by readers or observers that multiply information about it in the space of social and media realities within an open system.

Hence, studying public events as a mass communication phenomenon requires a comprehensive model of analysis of the object, with the ability to represent the data visually at different stages of the study. The analytic tools of representation must be no less spectacular than the expressive tools of representation of the public event’s message. MAXQDA allows you to construct such a model of analysis of cultural public events.

Eurovision Song Contest

The Eurovision Song Contest has a strong resonance within the media (and hence its relevance to this study) thanks to its 50+ year history on the one hand and the anticipation surrounding who will win on the other. The Eurovision Song contest has been running since 1956 and aims to bring together European countries into a large cultural community using a framework of culturally-based competition. It is broadcast not only in Europe but indeed worldwide.

The history of Eurovision also shows the development of cultural policies and telecommunications technology in Europe; every year the event becomes a platform for testing broadcasting innovations and for singers’ ambitions. Every year, organizers reinvent the contest with new information that gives it new meaning. These new meanings deal with old understandings and transform the general message about Europe integration with explicit and implicit meanings based on the current context and public experiences that are reflected in the mass media.

Eurovision 2017 as a Case Study

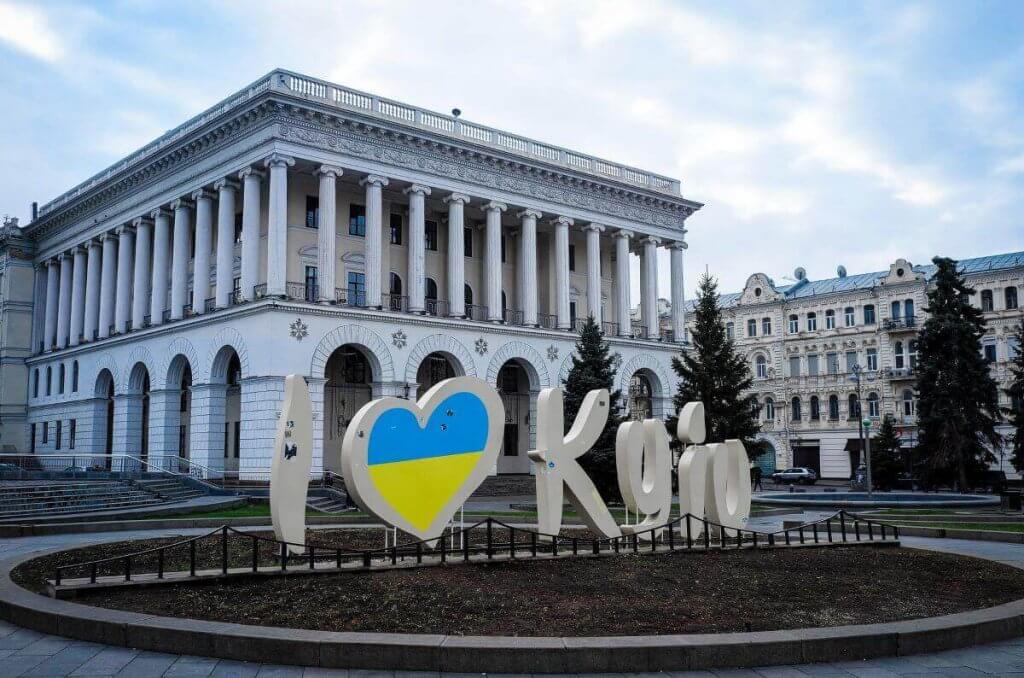

I thus analyzed the Eurovision Song Contest as a public cultural event by referring to the English language publications in the Ukrainian and European Internet media. Data collection took place in June of 2017, two weeks after the Eurovision Song Contest campaign in Ukraine.

The data analysis process was conducted from 2017 to 2019 at Viadrina European University (within the VIP Graduate program with the support of the DAAD) and V. N. Karazin’s Kharkiv National University (as part of my PhD project titled “Public event as an object of journalistic reflection in Ukrainian mass media”, currently still a work in a progress).

Using MAXQDA’s Word Cloud function to reveal tendencies:

The most used words in publications were ‘Eurovision’ (893), ‘Ukraine’ (413), ‘Song’ (397), and ‘Contest’ (364)

I chose to use the Eurovision Song Contest 2017 in Ukraine as a case study because it had a clear organizational structure, an official mission, messages that represented goals, and operational plans realized by professional agents in a specific context of time and space.

One notable feature of Eurovision is the inclusion of spectators as active participants in the evaluation of competitors. The general line of attention on the Eurovision Song Contests is focused on a series of concerts, the most popular of which is the final concert, which is prepared for throughout the year. Journalists and the public alike follow this public event from the moment it is announced until quite some time after the finale is over.

Step 1: What to Code and Why?

To define the transformation shifts we need to outline the structure of this public event’s effect. To do this, we adopt a coding process. The aim of this analysis step is to decode implicit shifts of a public event’s message based on the concept of four procedures by Allein Badiou: poem, matheo, politics, and love.

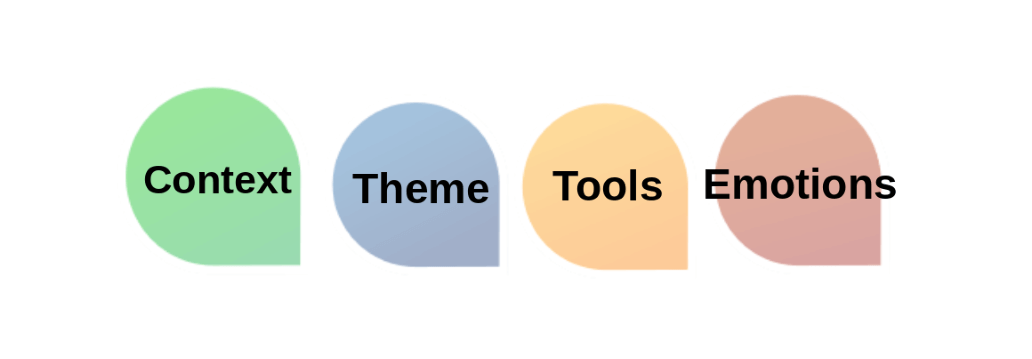

Initial analysis also allowed me to distinguish four thematic groups: context, theme, tools, and emotions. According to this concept, I identified four ontological levels of public events to code this public event (see screenshots below):

Four codes of analysis based on the concept of four procedures by Allein Badiou: poem, matheo, politics, and love.

- I linked Badiou’s politics with my group ‘context’, which is the set of circumstances of implementation, including the political situation and cultural memory.

- Poem correlated with my group ‘theme’ (the contest’s 2017 theme was “Celebrate Diversity”) to find the main message of the event.

- Matheo I linked with ‘tools’ to find the instruments of message construction, which were dependent on technologies and subjects of creation.

- Love goes with ’emotions’, as it is a reaction that shows the perception of a public event message.

Step 2: Visualizing the Analysis So Far

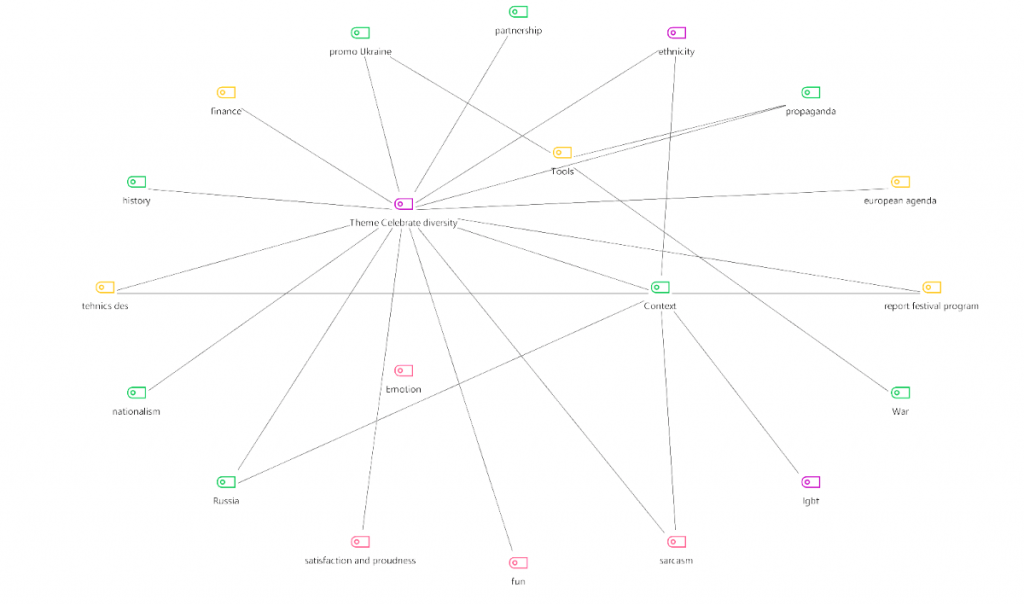

MAXQDA allows you not only to build a code system but generate a coincidence model, and once the coding process is complete, we can see a great web of connections and meanings (see screenshot below).

Using MAXMaps to create a coincidence model that shows the intersections of coded segments

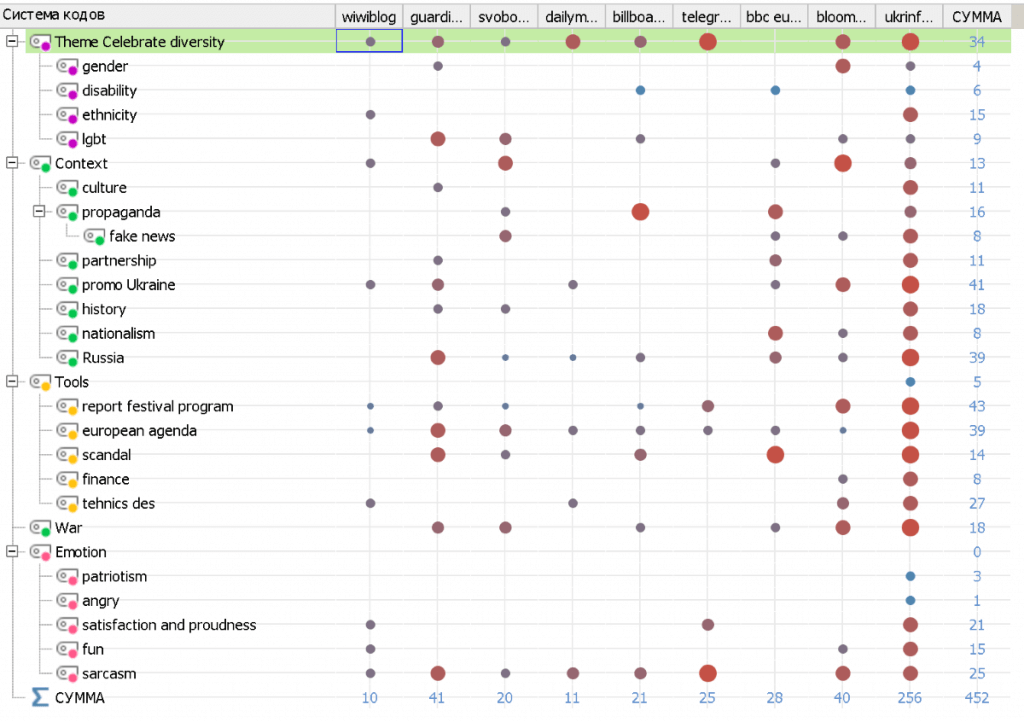

As we can see, many connections of coded segments are related to the Context, Tool and Theme. To see the intersections in more structured way, we can also use the Code Matrix Browser (see screenshot below):

Using MAXQDA’s Code Matrix Browser as a structured way to show intersections between different levels of analysis of the public event

Step 3: Placing Research in Context

In 2017, Ukraine hosted the Eurovision Song Contest for the second time. It could be said that in 2017, as in 2005, the song contest had additional political resonance, because it took place after the revolutionary events of the Maidans in 2004 and 2014. The announcement of Eurovision 2017 took place after the completion of the previous song contest and the 2016 winner, Ukrainian singer Jamala announced that the new host would be Ukraine.

Jamala’s victory had political connotations related to the content of her song. Jamala’s song was dedicated to the memory of the events of 1944 when the native inhabitants of the Crimean Tatars were deported from their homes. The song thus sparked associations with the 2014 events in Ukraine, when the Russian Federation annexed Crimea and launched hostilities in the eastern part of the country, and many residents were forced to move to other places. These circumstances have certainly fueled the interest of foreign journalists, as European tabloids had not been known to write about Ukrainian show business before.

Visualizing the Differences in Data Sources

My study examined 15 sources, 68 publications and videos: including issues of The Guardian, Billboard, BBC, Daily Mail, Bloomberg, and The Telegraph, which are known to pay attention to the popular international cultural events.

The new representative of media-agents for the Eurovision song contest was the WiWi-Blog, a niche alternative media specializing in coverage of show business issues. Radio Svoboda had also been covering the Eurovision for the first time, as this resource only covers events with human rights issues. Furthermore, most local bloggers did not participate in the coverage of the Eurovision Contest before 2017. And the last resource — Ukrinform, this news agency was the official national representative of the Eurovision Contest in Ukraine, which provided journalists with work during the competition.

To compare the balance of levels in the content of messages of different editions, I used another MAXQDA data visualization tool, the Document Portrait (see screenshot below):

Using MAXQDA’s Document Portrait function to compare coded segments across documents:

We can clearly see the balance between emotions and politics

I was thus able to draw some conclusions from my analysis:

- Political connotations predominate in BBC publications,

- and they are absent in the Telegraph.

- The WiWi-blog is the leader in the emotional representation of information.

The usage of politics or emotions in publications is a tool for attracting readers’ attention. However, further investigation is needed to see whether the appeal of politics is necessary for the success of the event in the media, or if the focus on politics is due to the format of the publication, or if there are other motives for that matter.

The Importance of Context

The answer to this question opens up opportunities for formulating conclusions on media and public relations policy, but it all depends on context. Specifically, one must examine the context in which the event is taking place and the context of how the media representation is being produced.

If one examines the competitions of previous years and the history of the creation of the Eurovision Song Contest in the 1950s, this competition always had political connotations surrounding it. It was created as a form of soft political power for the integration of European states into the European Union as a cultural community.

Step 4: Drawing Conclusions from the Analysis

Comparison of Eurovision 2017 publications in Ukrainian and European media provided a basis for identifying trends in public-media relations. I was able to draw three main conclusions from my coding and analysis of coded segments work:

- “Eurovision Song Contest” is not only about songs, but it is also about the relation between media and the public.

- European media and Ukrainian media have different approaches to reporting about diversity (according to current context).

- Ukrainian media uses propaganda-based rhetoric as a specific method for addressing inside and outside media-audiences.

The Code “Context”

The subject of the discussion in the coded segments is the circumstances around which the contest is being held: political situation, political leaders, participants of the competition as representatives of certain countries, Ukraine in the world, etc.

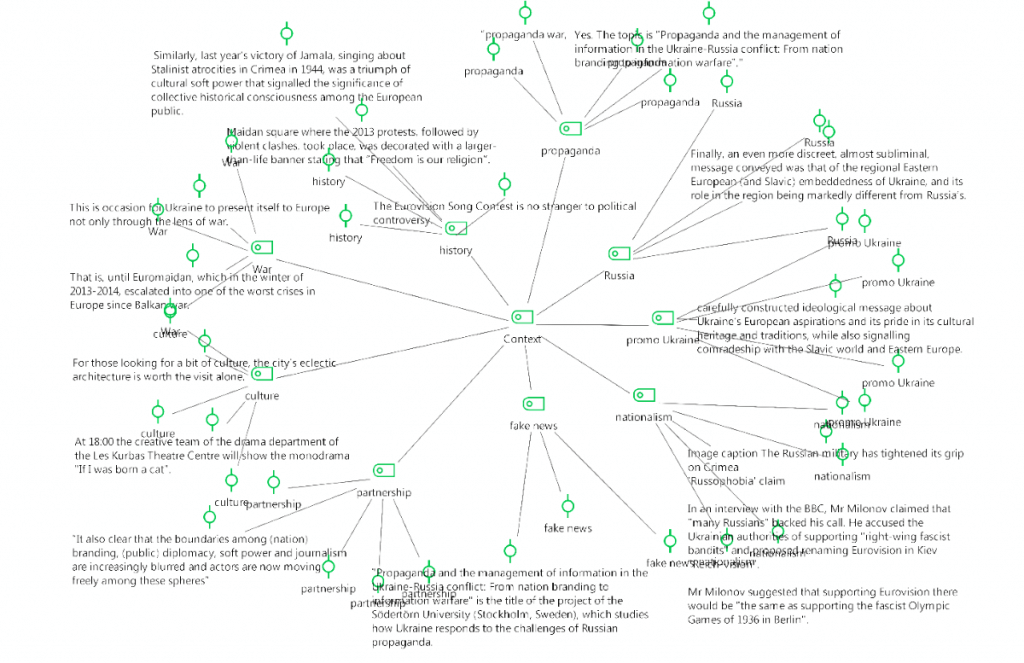

I used subcodes to highlight the specific issues: propaganda, fake news, culture, partnership, promo Ukraine, history, nationalism, and Russia. The Code-Subcodes-Segments model in MAXQDA’s MAXMaps feature allowed me to conduct an in-depth analysis visually because I could see which topics are the most discussed. It also helped me prioritize the focus on journalistic reflection at each level (see screenshot below).

The Code-Subcodes-Segments model allowed me to see which topics are the most discussed by journalists on ‘context’ level

An in-depth analysis of the coded segments showed that the representation of a public event in the media occurs through existing frames and patterns of perception of objects of reality. Ukraine is presented either through the political frame of its relations with Russia or through the cultural frame as a new tourist object (attractions, landscapes, food, people). Similar framing is inherent in both European and Ukrainian media.

However, from this specific moment in Ukrainian media publications, we can outline a tendency towards “promo-schizophrenia”: the messages seem to be addressed to foreign readers because the materials are translated into English, but they also have propaganda rhetoric that is used to address the readers of post-Soviet Ukraine directly. It looks like a simultaneous appeal to both internal and external consumers of information.

The Code “Theme”

The official media campaign of Eurovision 2017 started in January of that year with the slogan “Celebrate Diversity”. The slogan was posted on the official website of the competition, which is re-created annually, specifically to serve as the main source of Eurovision information.

The effort in maintaining the website is justified because journalists and publications refer to information on the site as the primary source of official information. The official website was thus also the starting point for this study’s examination of the development of a discourse of a public event in the media.

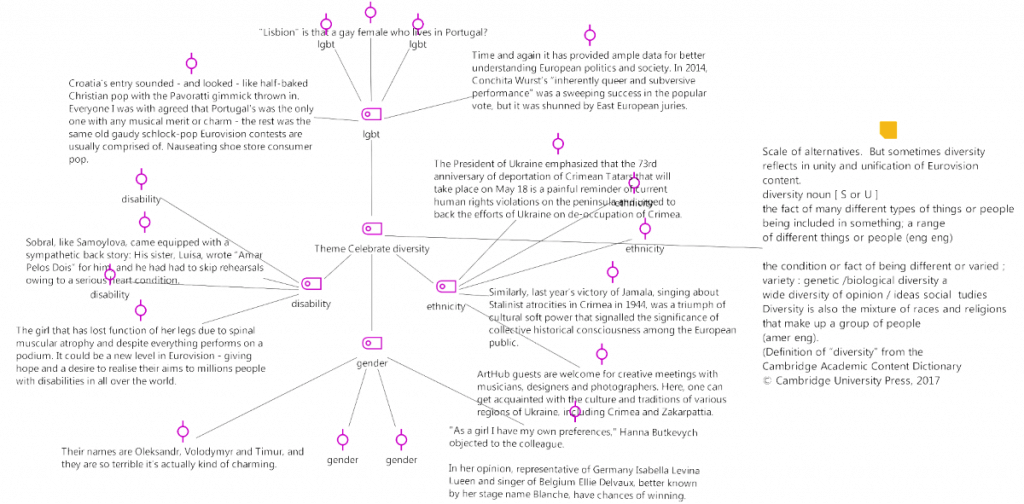

I used the code ‘theme’ on segments related to creating discourse around a public event – the meaning of the slogan, the official statements, and the relevance of representation in accordance with the expectation of the public. The official tagline of the Eurovision 2017 contest was chosen as the basic analytical unit and the subcodes I used were gender, disability, ethnicity, LGBT (see screenshot below).

The Code-Subcodes-Segments model allowed me to see which topics are the most discussed by journalists on ‘theme’ level

Alongside the tagline, a visual symbol was used to represent the competition: the traditional Ukrainian necklace, which is not only the oldest form of women’s jewelry in Ukraine but is also considered a charm. The unique feature of the decoration is that it consists of a large number of different beads, each of which is special.

The message also emphasizes the slogan of the contest: “This year’s Eurovision slogan is important for the song contest. Celebrate Diversity is about the unification of Europe and beyond, whose citizens come together to honor what unites us and what sets us apart, makes us unique. Good music is also combined”, said Eurovision Executive Director Ion Ola Sand.

The logo as part of the message was perceived by the public and journalists as a cultural object, which, in fact, has the value of representing Ukraine in the European family as a territory of tolerance and respect for diversity. This symbol has not caused a heated debate, which may indicate the appropriateness of branding.

Nonetheless, the slogan “Celebrating diversity” had a different reception in Ukrainian and European media. In the “European tradition” the word “diversity” is part of a discourse of non-discrimination and a tolerant attitude towards representatives of different minorities, which corresponds to the perception of Eurovision as a platform for the representation of discriminated groups.

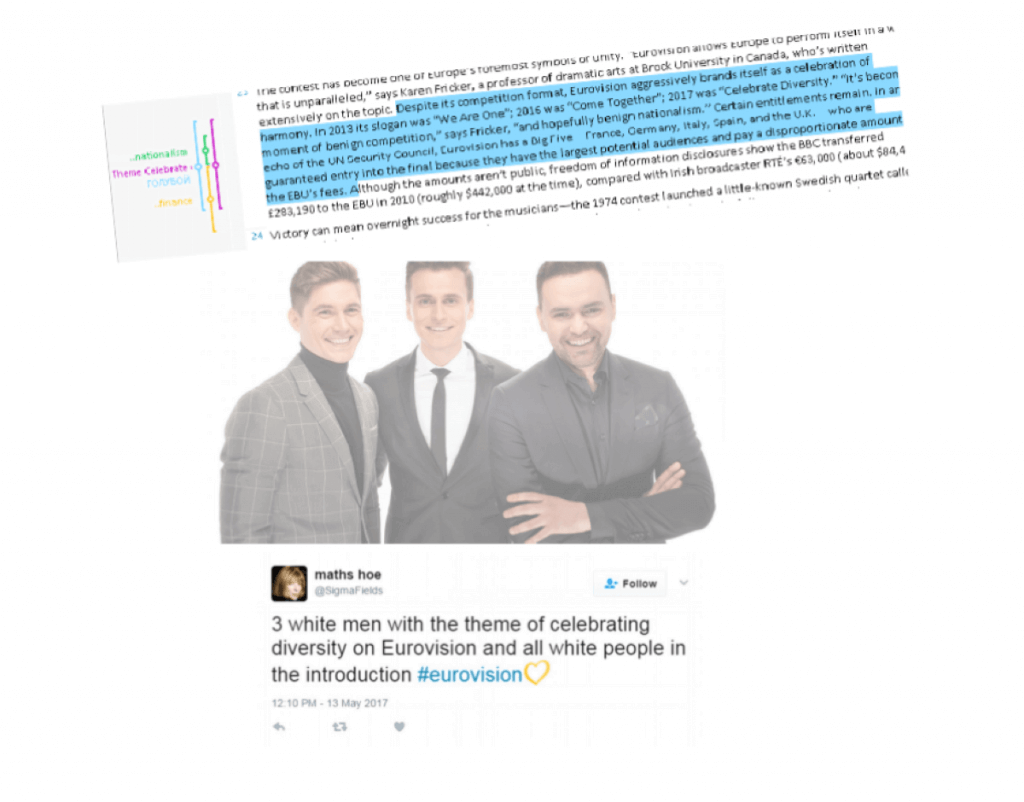

The fact that caught the attention of the journalist was therefore that the local organizers chose three white, young, men to host the competition. On the first day of the contest, the Telegraph published a tweet, which garnered 200 comments at once. It was joked about the fact that the “three white male millennials” do not quite reflect the idea of the slogan “Celebrate Diversity”. Discussions were picked up by journalists from other publications, including the Guardian and the Daily Mail (see screenshots below)

Coded segment with tweet about “three white male millennials” as the leaders of Eurovision 2017 with the motto “Celebrating diversity”

In the Ukrainian press, however, this discussion was not continued. The Ukrainian press was mostly interested in local questions and problems: “Will there be new elements of improvement in the capital because of Eurovision?”, “will a singer from Russia come to the competition?”, etc.

The Ukrainians preferred to accept the motto “Celebrate Diversity” as an alternative and a metaphorical victory for the diversity of consumer choice, which in the minds of the post-Soviet people is linked to the victory over the Soviet tradition of restricting the right to choose everything you want. Thus, creative representation receives the reactions of consumers of information according to the context in which it takes place.

Furthermore, in journalistic materials on Ukrainian internet resources, we mainly observe monotonous reprints of official statements about Ukraine’s integration in Europe, journalists reporting on events without expressing their opinion, and a general lack of analysis of events and facts. This trend can be seen as based on the historical context of Ukrainian journalism having evolved from the propaganda canons of Soviet journalism, which were unrelated to audiences and dependent on state order.

I therefore believe that in order to find out the motives behind media frames, it is necessary to determine whether they are a part of a creative concept or an instrumental necessity.

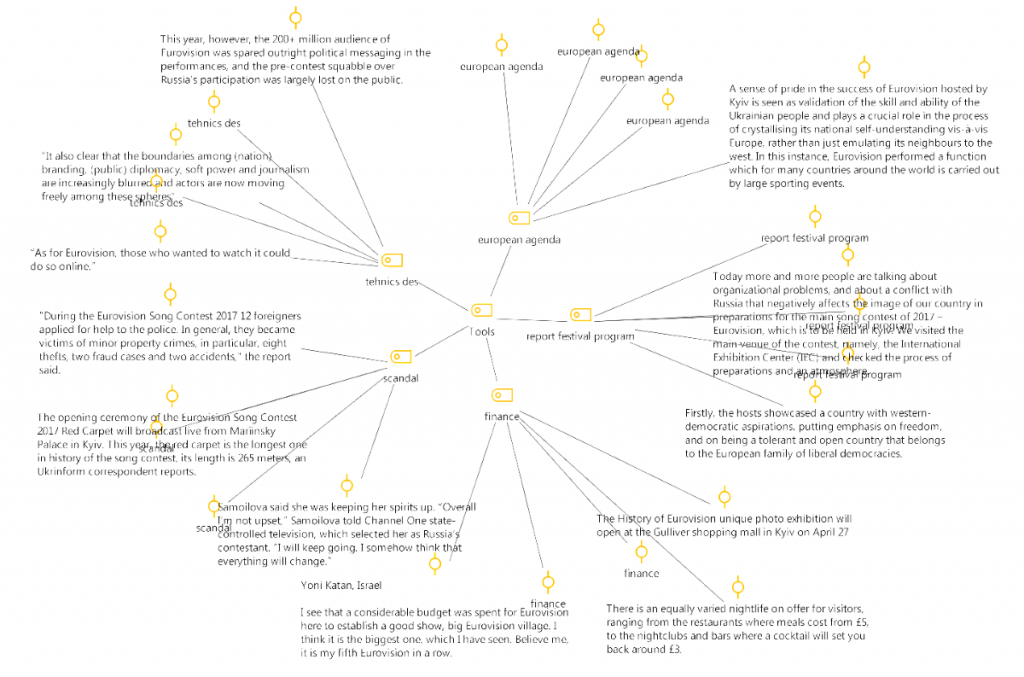

The Code “Tools”

On the instrumental level, we examine coded segments I coded with the group “tools”. This code was used to extract information such as the program of the contest (what, where, when, how), the European agenda, scandals, finances issues, and technical information (see screenshot below).

The ‘tool’ level analysis allowed me to determine the intentions of the media to cover certain facts as an instrument of attraction

Information on this level not only has factual value, but it is about the impact of technologies used to attract the attention of audiences, including manipulations of words and meanings. For example, the presence of a scandal is not an undesirable structural element in the Eurovision contest. In fact, if you look at the descriptive article of the Eurovision on Wikipedia, the topic of scandals is highlighted separately.

This strategy is understandable in terms of the viral effect scandals have in mass media. One such scandal I found was the refusal of Ukrainian organizers to allow the Russian singer to participate because of their violation of the rules when crossing the Ukrainian border. Information about this scandal was transmitted through political (relations between Ukraine and Russia) and humanistic (discrimination because the singer is a disabled person) frames.

The tool-level analysis allowed me to determine the intentions of the media to cover certain facts as an instrument of attraction. Specifically, we can see it if the fragments have double or triple encoding through the coincidence model.

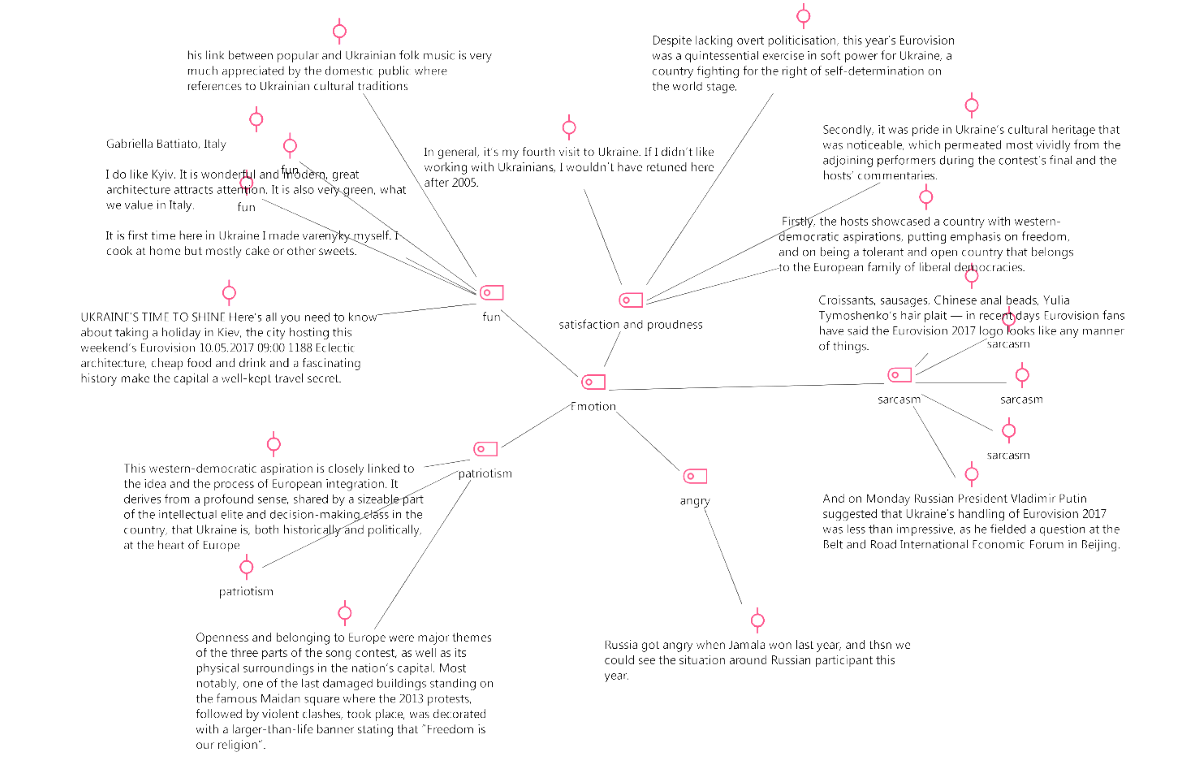

The Code “Emotions”

The subcodes for ’emotions’ I used were: patriotism, anger, pleasure and pride, fun, and sarcasm (see screenshot below).

The typology of emotion allowed me to better understand reactions, specifically, what affected the consumers

Appealing to emotions as a tool for creating a message, or as a fact of social reaction to a proposed message of a public event, prevails in publications when journalists deviate from classic journalistic standards. We see the use of emotions particularly in blogs, tabloids, and reader comments. Authors used emotional vocabulary or pay attention to the facts of a public event that evoke emotions because such appeals can mark material for the consumer as important.

Naturally, the main source of emotional response to Eurovision comes when discussing the winner or losers. This is what is not a hidden tool, as it relates to the direct meaning of the Eurovision Song Contest – competition. Understanding public cultural events as messages aimed to realize the strategic and tactical goals of national cultural diplomacy gives journalists reason to speak about this cultural event in the context of political discourse. Of course, the media’s main reason for publication is the song contest and the intrigue who will win, but it should be noted that this meaning is not the last one.

Conclusions: Using MAXQDA to Identify Trends in Public-Media Relations

The analysis of coded segments gave me an understanding of the context of the organization of a public event, both cultural and political, revealing the public event to be a catalytic / determinant / representative environment, formed as a result of creative construction of reality for the purpose of supervision or changes of relations between the media and public.

I coded my data with MAXQDA and then conducted an in-depth analysis of coded segments, which allowed me to identify reactions as markers changes. Constructing models helped me analyze the discourse around a public event as a multi-level structure that include representations of the positions of agents involved in the interaction on the stage of creation (before the reaction to the public event message), on the stage of representation (report about reactions to the public event message), and stage of interpretation (ideas about the reactions). In conclusion, modeling media research with MAXQDA allowed me to carry out in-depth analyses of objects in the media field and to find out which communicative actions provoked discourse in the media.

This study inspires me to test the model on other examples of other cultural public events for my continued dissertation research in 2019-2020. For further information concerning public events as a result of the social and media interactions, please check out my article:

“Public event effect: representation of social and media interaction”

About the Author

Olena Zinenko is a Ph.D. student and lecturer at the V. N. Karazin’s Kharkiv National University, Faculty of Sociology, Department of Media Communication. She is the coordinator of social projects and curator of media platforms, as well as a “founder of new traditions and reinventor of old customs”. She currently lives and works in Kharkiv and her credo is: “action is a message”.

Olena Zinenko is a Ph.D. student and lecturer at the V. N. Karazin’s Kharkiv National University, Faculty of Sociology, Department of Media Communication. She is the coordinator of social projects and curator of media platforms, as well as a “founder of new traditions and reinventor of old customs”. She currently lives and works in Kharkiv and her credo is: “action is a message”.

Olena Zinenko is a Ph.D. student and lecturer at the V. N. Karazin’s Kharkiv National University, Faculty of Sociology, Department of Media Communication. She is the coordinator of social projects and curator of media platforms, as well as a “founder of new traditions and reinventor of old customs”. She currently lives and works in Kharkiv and her credo is: “action is a message”.