Over the past decade, history has embraced the so-called material turn in methodology (Clever & Ruberg, 2014). This led to an increased interest in past embodied practices and humans’ tinkering with all things material. One of the off-shoots of this interest is the rise of the “artisanal histories” (Smith, Meyers, & Cook, 2014), i.e. historical studies focused on referential rather than narrative sources. The key difference, as explained by historian Kalle Pihlainen (2019), lies in that, unlike referential texts, narratives, including literary fiction, fulfill their intended purpose independently from the material world – as long as the reader is immersed, disbelief is suspended and one is free to revel in imagined worlds with dragons and fairies. The referential sources, on the other hand, ‘refer’ the reader to the material world outside of the narrative, i.e. they make claims about causal relationships happening in the physical environment experienced by the reader. To illustrate: a medieval chronicle is a narrative, as it invites readers to an imagined world within the text, but a cooking recipe from the same period is a referential text, because it claims that by following certain instructions readers will produce predictable effects in their material environment, outside of the text. And hence, referential texts can be tried or tested against the physical world. To quote Pihlainen: „Without this ‘materiality’ reaching into the reading – without the reader’s mindfulness of reality as a part of the communication — referential writing would simply not make sense as a genre” (2019, p. 72).

In my own research, I focus on referential texts of a peculiar kind – the so-called ‘fight books’ (Jaquet, Verelst, & Dawson, 2016). These texts were written in the late Middle Ages by people who claimed expertise in various martial arts and, at least in some cases, attempted to preserve their embodied knowledge of these practices in writing. As such, they routinely made references to causal relationships involving not only artefacts, but also the laws of physics and functions of a human body. This makes it next to impossible to extract their epistemic content in full by reading alone – body and motion have to be harnessed to reach their deeper content. In one of my previous posts (https://www.maxqda.com/blogpost/corpus-based-linguistic-research) I described how text-analytical methods, such as corpus-based linguistic research, can be used to gain crucial insights enabling such an embodied approach to these sources. Here, I would like to go one step further and provide an example how MAXQDA can facilitate and enrich the conversation between referential texts and attempts at their hands-on investigation. In short, I am going to showcase how I am currently using the software to simultaneously analyse texts and visuals (images and videos).

BUILDING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN TEXTS AND VIDEOS

My study design is, in fact, quite simple. I work mainly with a 14th/15th-century German fight book written by an anonymous martial arts practitioner which can be classified as a referential text – it contains numerous claims about effects produced in combat by different behaviours. I use these claims as guidelines for hands-on experimentation. To put it simply: together with my co-researchers I try to carry out the instructions given in the fight book. These trials are documented textually, in the form of a field journal updated daily, and visually, as video recordings. I follow the same procedure for my secondary historical sources, i.e. other texts relevant for my research, such as medieval treatises on physical conditioning (yes, they may have lacked smartwatches, but fitness was definitely a thing in the Middle Ages!).

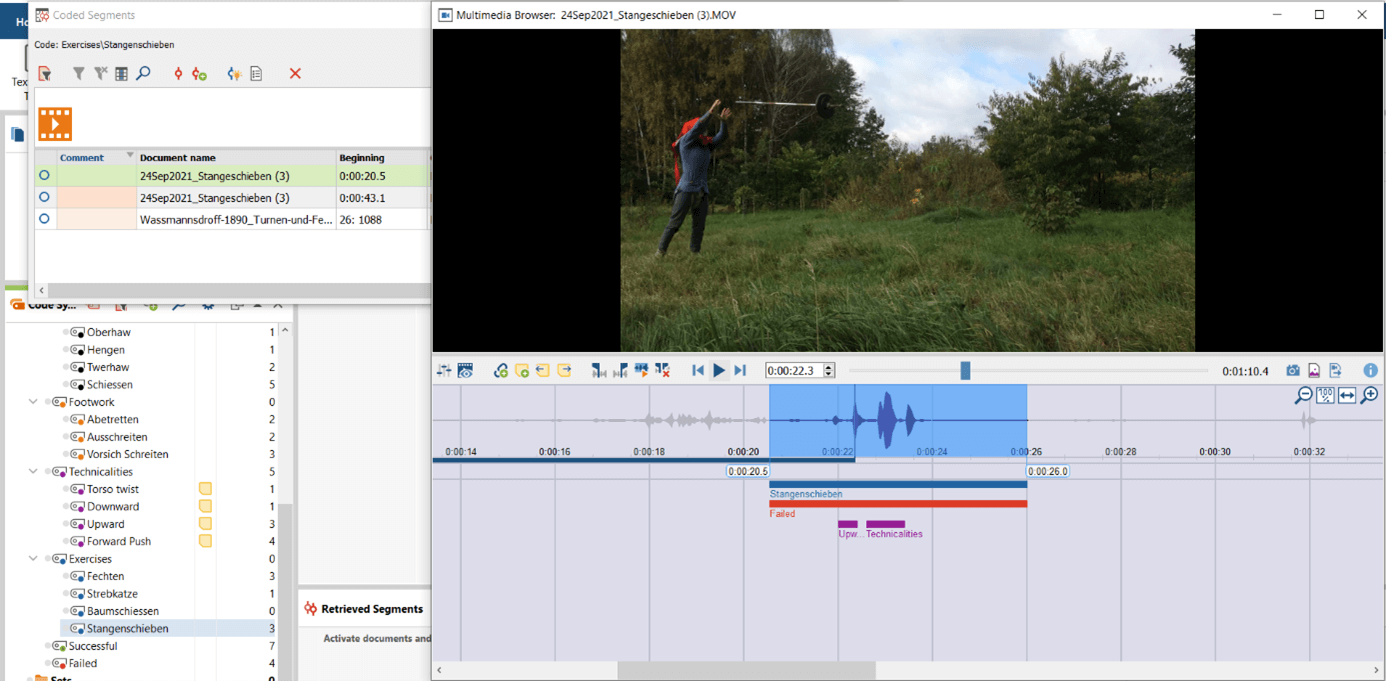

In effect, I end up with the following documents in need of analysis: 1) historical texts and images; 2) field research journal; and 3) video documentation. Importantly, due to practical reasons, not all of my experimental trials are video-recorded and often a video is produced before or after a relevant observation is noted down in my journal. At times, several experiments carried out in long intervals connect to a single observation. Moreover, my journal entries routinely refer simultaneously to specific fragments of a historical source and particular moments in recorded experiments. Keeping track of these connections manually would be a daunting task for a team of undergrads, let alone a lone-wolf PhD candidate, like myself. Fortunately, MAXQDA is extremely helpful in tackling this problem. By coding all three categories of my documents in a single project it is easy to retrieve all sources, journal entries, and videos dealing with the same subject matter, e.g. a selected physical exercise techniques (Figs. 1 & 2).

Figure 1. Coding videos and texts together in a single project offers me easy access to textual and iconographical sources on late-medieval physical exercises as well as to recordings of their modern reconstructions.

Figure 1. Coding videos and texts together in a single project offers me easy access to textual and iconographical sources on late-medieval physical exercises as well as to recordings of their modern reconstructions.

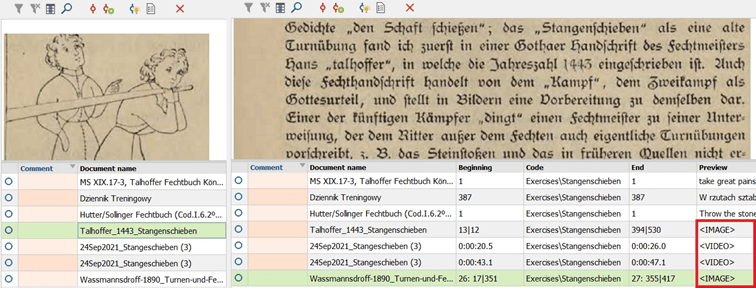

Figure 2. The elementary function of retrieving segments coded in activated documents is already extremely useful while dealing with mutliple categories of sources on the same phenomenon – late-medieval exercises in my case. In the MAXQDA Retrieved Segments window, the „Preview” column either contains text, if the document is textual, or indicates the type of media in other cases, e.g. „Image” or „Video” (see the red square in the bottom right). This way, checking for compatibility between descriptions, depictions, and reconstructions of investigated exercises is much smoother, as I don’t have to manually browse through different folders or craft complicated file-naming schemes.

Figure 2. The elementary function of retrieving segments coded in activated documents is already extremely useful while dealing with mutliple categories of sources on the same phenomenon – late-medieval exercises in my case. In the MAXQDA Retrieved Segments window, the „Preview” column either contains text, if the document is textual, or indicates the type of media in other cases, e.g. „Image” or „Video” (see the red square in the bottom right). This way, checking for compatibility between descriptions, depictions, and reconstructions of investigated exercises is much smoother, as I don’t have to manually browse through different folders or craft complicated file-naming schemes.

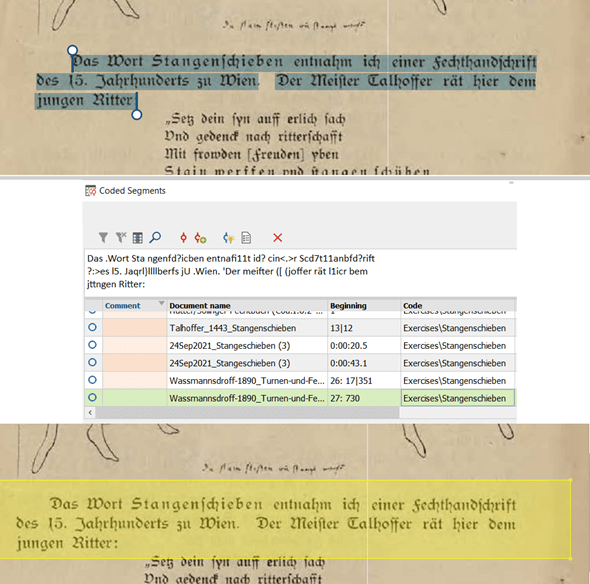

As a sidenote, during this project I also came to appreciate a simple functionality – the possibility to mark PDFs either as text (if they have been put through OCR) or images. Its appeal may escape most researchers, but for me it was often a life-saver, since OCR tends to have a hard time properly recognising older scripts. In these cases, coding them as images is usually a much more efficient option yielding easy-to-read previews (Fig. 2), whereas coding them as text returns gibberish (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. With PDF files containing texts written in older scripts it is often possible to code their content as both text (top) and image (bottom). However, in such cases the latter way is better, since coding as text often results in illegible previews in the Retrieved Segments window (middle), due to OCR technology’s poor handling of non-modern fonts.

Figure 3. With PDF files containing texts written in older scripts it is often possible to code their content as both text (top) and image (bottom). However, in such cases the latter way is better, since coding as text often results in illegible previews in the Retrieved Segments window (middle), due to OCR technology’s poor handling of non-modern fonts.

FINE-TUNING THE ANALYSIS WITH MULTI-MODAL PERSPECTIVES

In my research I seek to develop a bottom-up approach to investigating late-medieval physical culture. This forces me to pay close attention to kinaesthetic details preserved in historical sources as well as those revealed by modern reconstructive experimentation. Qualitative coding turned out to be very helpful in this regard, because it is in itself an epistemic process. Assigning a code requires meticulous reading (texts) and watching (videos, images) and thus helps discover details or connections that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Let us take an example of the late-medieval exercise called Stangenschieben (“throwing rods, poles, or bars”). Its available historical descriptions and depictions are vague, providing hardly any clues to how it should be performed. The only certainties I had at the onset of the project was that it had involved throwing a bar (of iron or wood), shaped as an elongated cone, as far as possible starting with the bar placed on the shoulder (see Fig. 2, bottom left), and that the distance thrown would be calculated from the thrower to where the wider end of the bar landed. It was also described as a feat requiring and developing strength. Attempts at performing the exercise revealed that there were two ways to throw the bar which would produce the longest distances while conforming to the aforementioned historical guidelines. During field research, it seemed impossible to decide which way would be closest to the historical performance, but further analysis combining the field journal, historical sources, and video documentation provided important insights.

Videos of reconstructed exercises were coded with a system of labels describing their basic kinaesthetic components, such as whether the motion followed a downward (e.g. a squat) or upward trajectory (e.g. jump), etc. In the case of two versions of Stangenschieben, the only differences in how they were coded were related to the manner of propelling the bar and the way it landed. One involved a forceful upward motion with the hands (coded Upward) which resulted in the bar “flipping” mid-fly (coded Stangenschieben/Flip), so that the narrower end landed farther (Fig. 4), whereas the other used an energetic push forward with the hands (coded Forward push) resulting in the bar flying more like an arrow or javelin (coded Stangenschieben/Straight) and landing with the wider end farther from the thrower (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise, the movement variant in which the final stage involves raising the arms high and flipping the thrown object around (thus coded as Upward and Flip).

Figure 4. Experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise, the movement variant in which the final stage involves raising the arms high and flipping the thrown object around (thus coded as Upward and Flip).

Figure 5. Experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise, the movement variant in which the final stage involves pushing the arms forward projecting the thrown object straight ahead of the thrower (thus coded as Forward push and Straight).

Figure 5. Experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise, the movement variant in which the final stage involves pushing the arms forward projecting the thrown object straight ahead of the thrower (thus coded as Forward push and Straight).

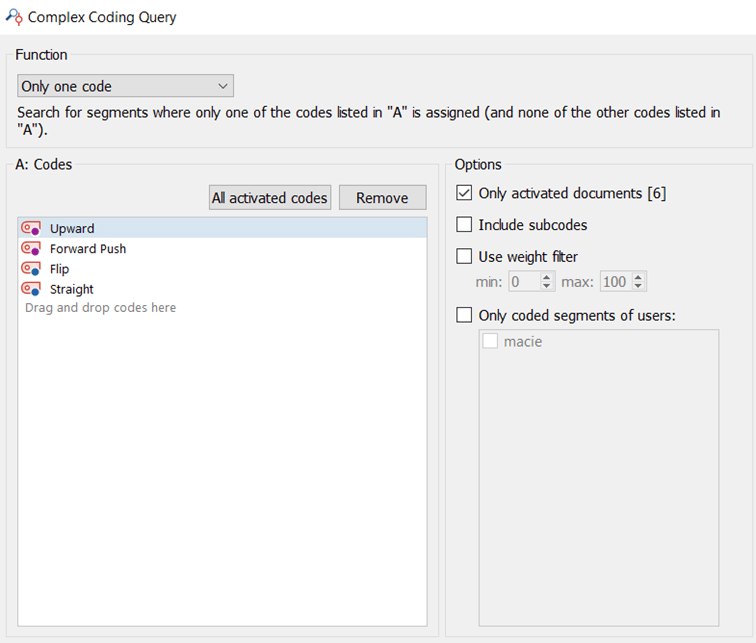

In order to explore it further, I right-clicked the code Stangenschieben and used the “Activate Documents Containing this Code” function. Next, a Complex Coding Query was performed to retrieve those segments within the activated documents which contained one of the codes related to variants of the exercise: Upward, Forward push, Flip, or Straight (Fig. 6). This search mostly retrieved timestamps from video recordings, but also one entry from the field journal. There, an observation was made that out of the two throwing methods the Straight was perceived during try-outs as much more strenuous than the Flip, as in the latter “the final stage of motion does not involve pushing and accelerating the bar but only rotating it around its own centre of mass” (translated excerpt from the journal). Given that the historical sources claimed Stangenschieben to be a strengthening exercise, it would suggest that the Straight variant was more correct.

Figure 6. Complex Coding Query is a versatile tool, because its „Function” menu (upper left) contains a number of options allowing to retrieve various combinations of codes. I found it extremely useful in dealing with my project spanning different media (texts, images, and videos), long period of time (12 months), and large amounts of data (hours of video recordings, several historical texts, and 160 pages of the field journal).

Figure 6. Complex Coding Query is a versatile tool, because its „Function” menu (upper left) contains a number of options allowing to retrieve various combinations of codes. I found it extremely useful in dealing with my project spanning different media (texts, images, and videos), long period of time (12 months), and large amounts of data (hours of video recordings, several historical texts, and 160 pages of the field journal).

REVEALING DEEPER LAYERS OF INTERCONNECTEDNESS

The observation described in the previous section prompted me to probe my data even further. In an exploratory move, I once again performed a Complex Coding Query, this time extended to all my documents and asking for an intersection of codes Forward push and Successful. I chose these two codes, because I was curious about what other exercises or martial techniques, be it in my historical sources, field journal, or video documentation, made efficient use of the pushing involved in the presumably more correct variant of Stangenschieben. The search yielded a number of results, such as different throwing motions (e.g. shot put with stones, historically called Steinwerffen) or wrestling moves. Disappointingly, upon closer scrutiny the majority of them turned out to be performed with a single arm and thus differed importantly from the two-handed pushing seen in my videos on Stangenschieben (Figs. 4 & 5). However, one motion was different – a sword-fighting technique known as Schiessen (“shooting”). It was one of the essential motions designed for a two-handed sword and also shared the crucial kinaesthetic features with the Straight variant of Stangenschieben (Fig. 7). Even more importantly, the only consistently recurring difference related to bodywork between those recordings of Schiessen which were labelled as Failed and those marked as Successful was, respectively, the absence or presence of the Forward push.

Therefore, if one takes into account that the exercise of Stangenschieben was, as per historical sources, designed for physical conditioning of late-medieval knights and men-at-arms, then its kinaesthetic affinity to the important sword-fighting technique of Schiessen is likely not coincidental. On the one hand, this finding frames Stangenschieben as a highly functional exercise meant to enhance martial performance. On the other, since Schiessen’s success appears crucially dependent on the kind of motion I coded as Forward push, then it corroborates the similarly-performed Straight variant of Stangenschieben as the correct reconstruction of this exercise.

CLOSING REMARKS

As demonstrated, even for historians MAXQDA is a powerful tool for research mixing different media. Its usefulness goes well beyond basic, but still very handy, functionalities, such as capturing still frames or coded fragments from videos and transforming them into separate project documents, which may then be exported as JPEGs, PNGs, or movie clips (guess how I made the figures for this text!). From my perspective as a researcher using modern video recordings to enhance the reading of late-medieval texts, the main strengths of MAXQDA lie in the programme’s ability not only to quicken but also to deepen the analysis. Gaining the insights described above would have been next to impossible without such analytical tools as the Complex Coding Query or the possibility to code videos by their fragments and to view them directly in the Retrieved Segments window.

Figure 7. Still frames from different documentation videos comparing the motion coded as Forward push in the experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise (left) and during execution of the sword-fighting technique of Schiessen in a realistic experiment at a historical fencing competition (right). Note the similar final position of the arms and the leaning forward but straight torso in both cases.

Figure 7. Still frames from different documentation videos comparing the motion coded as Forward push in the experimental reconstruction of the Stangenschieben exercise (left) and during execution of the sword-fighting technique of Schiessen in a realistic experiment at a historical fencing competition (right). Note the similar final position of the arms and the leaning forward but straight torso in both cases.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clever, I., & Ruberg, W. (2014). Beyond cultural history? The material turn, praxiography, and body history. Humanities, 3(4), 546–566. https://doi.org/10.3390/h3040546

Jaquet, D., Verelst, K., & Dawson, T. (eds.) (2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

Pihlainen, K. (2019). The Possibilities of ‘Materiality’ in Writing and Reading History. História da Historiografia: International Journal of Theory and History of Historiography, 12(31), 47–81. https://doi.org/10.15848/hh.v12i31.1527

Smith, P. H., Meyers, A. R., & Cook, H. J. (eds.). (2014). Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

About the Author

Maciej Talaga is a PhD candidate within the interdisciplinary post-graduate course “Nature Culture” at the Faculty “Artes Liberales” (University of Warsaw) and a member of the European Committee for Sport History (CESH) and the Society for Historical European Martial Arts Studies (SHEMAS). He investigates late-medieval and early-modern European martial culture and works to develop a praxiographic and embodied methodology for his research. He is also interested in applying computer-assisted qualitative analyses into his practice as an archaeologist-historian. You can learn more about the programme he is involved in here: Nature-Culture Programme

Maciej Talaga is a PhD candidate within the interdisciplinary post-graduate course “Nature Culture” at the Faculty “Artes Liberales” (University of Warsaw) and a member of the European Committee for Sport History (CESH) and the Society for Historical European Martial Arts Studies (SHEMAS). He investigates late-medieval and early-modern European martial culture and works to develop a praxiographic and embodied methodology for his research. He is also interested in applying computer-assisted qualitative analyses into his practice as an archaeologist-historian. You can learn more about the programme he is involved in here:

Maciej Talaga is a PhD candidate within the interdisciplinary post-graduate course “Nature Culture” at the Faculty “Artes Liberales” (University of Warsaw) and a member of the European Committee for Sport History (CESH) and the Society for Historical European Martial Arts Studies (SHEMAS). He investigates late-medieval and early-modern European martial culture and works to develop a praxiographic and embodied methodology for his research. He is also interested in applying computer-assisted qualitative analyses into his practice as an archaeologist-historian. You can learn more about the programme he is involved in here: