Guest post by Jessica Penney.

An Indigenous Research Methods-guided MSc dissertation project in Labrador, Canada: Understanding Changing Conceptions of Health using MAXQDA

Welcome to my first fieldwork diary entry! This will be the first blog entry of three, where I will discuss my research topic, what my fieldwork consisted of, and how I used MAXQDA 2018 in the field to guide my ongoing work. In future posts, I will discuss how I used MAXQDA to analyze the data I collected and am presenting at conferences about this research.

View from Happy Valley-Goose Bay’s Birch Island Boardwalk

My project is titled, “The safety that was, is gone”: Muskrat Falls and Labrador Land Protectors’ Changing Health and Wellbeing. This research was my MSc in Global Health dissertation project, designed and undertaken by me during the summer of 2018. The dissertation explores health concerns held by a grassroots group of activists called the Labrador Land Protectors, who are resisting the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador, Canada (in the north-east part of the country).

Health concerns are key to this resistance, as the project is anticipated to raise methylmercury levels in their food sources, and residents are concerned the dam could break and flood their community. I am personally connected to this issue, as my family is from the region and will be affected by the project if these issues come to fruition. My positionality is something I have tried to be reflexive about wherever possible throughout my work.

Labrador Land Protectors

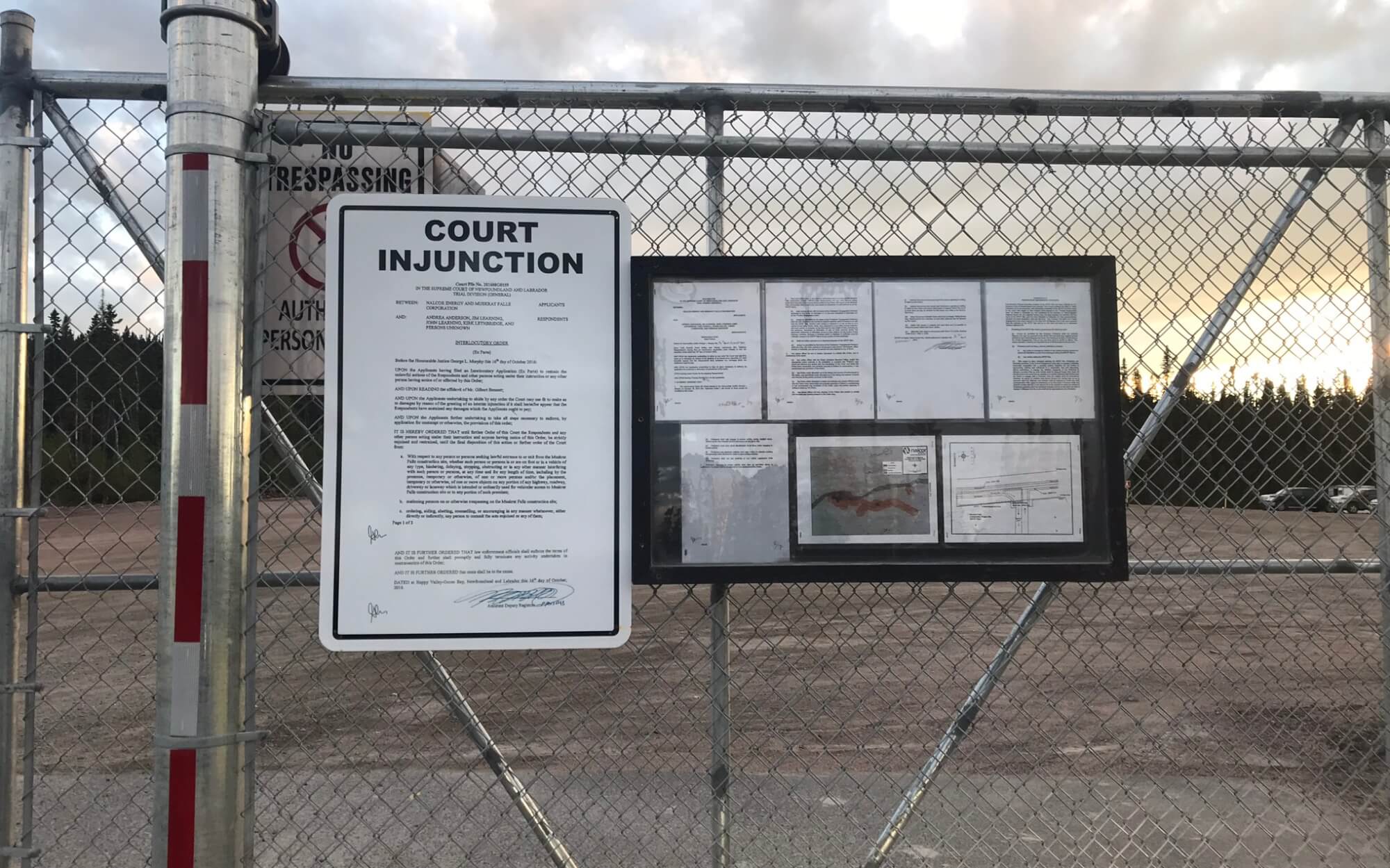

My research partners are members of The Labrador Land Protectors, a group that was established in contrast to the Muskrat Falls project. They are a group of ethnically diverse citizens who center the importance of land and water (and all of the benefits they provide) to Indigenous peoples, and Labradorians as a whole, in their activism. Throughout their resistance to the project, they have, for example, been active on social media, protested at the site of the project, and over the summer hosted a chain fast to raise awareness for their cause.

Site of protests at the Muskrat Falls Hydroelectric Facility.

Up to date information about the Land Protectors and their current efforts can be found at their Facebook page, and Twitter account.

Indigenous Research Methods

I used an Indigenous Research Methods (IRM) paradigm for this work, which is based on the values of reciprocity and accountability. In practice, this meant that I was interested in how understandings of health are socially constructed through interactions with the environment and other people. It also meant that I wanted to build reciprocal and respectful relationships with the community I was working with, so I worked closely with the Labrador Land Protectors to make sure they were comfortable with the research being done, and I will provide them with a lay report of findings.

I chose to enact IRM because I am Indigenous (Inuit), many participants were as well, and the project took place on Indigenous land. Labrador is the traditional home of Nunatsiavut Inuit, Innu First Nations, and NunatuKavut Inuit.

To mobilize IRM, I used the following data collection methods:

- Semi-structured interviews with 13 people,

- a sharing circle, a form of conversational practice used by many Indigenous peoples worldwide and by other researchers,

- and a brief questionnaire with participants to gain demographic information and triangulate responses with interviews.

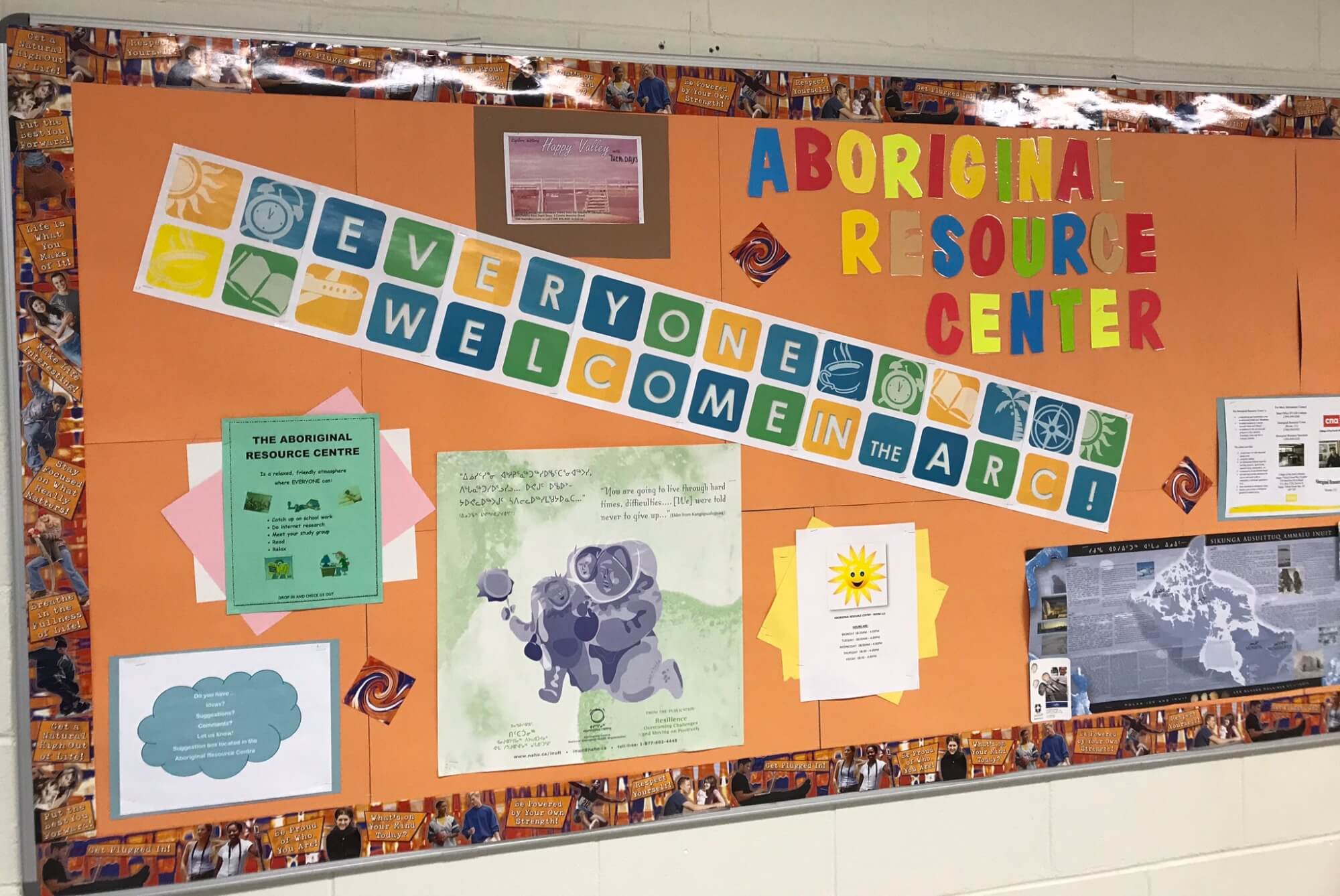

The Aboriginal Resource Center at the College of the North Atlantic, where the sharing circle took place on July 3, 2018.

I will discuss the analysis of my fieldwork data with MAXQDA and my research results in future blog posts.

Gathering Fieldwork Data with MAXQDA

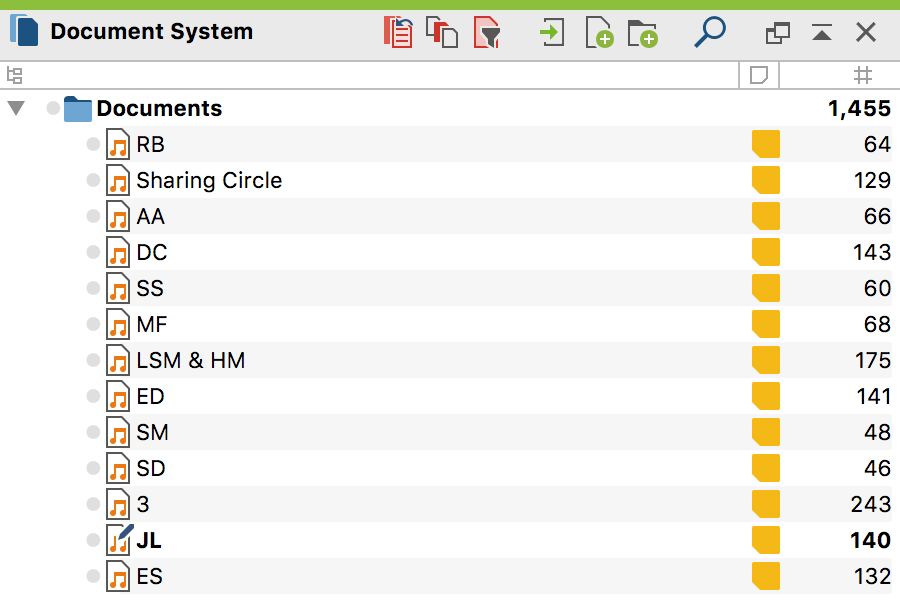

I spoke to 14 individual Land Protectors during my fieldwork, discussing why they became involved in the cause, how the hydroelectric project and resisting it had affected their life so far, and how they anticipate it affecting them into the future.

Working with the Labrador Land Protectors to gather data was a very fulfilling and humbling experience. Everyone I spoke with was honest, welcoming, and eager to share. I think my use of Indigenous Research Methods allowed me to form deeper connections with participants because I was not limited to trying to be “objective”. Instead, I was able to enter a reciprocal relationship, in which people told me their concerns, and I also shared mine, while also being reflexive about my position as both a researcher and community member.

Document System with all interviews and sharing circle listed

Transcribing in the Field

During my fieldwork, I used MAXQDA to transcribe my audio-recorded interviews. This was an easy, efficient process. In earlier research, I was required to type in a Word document while listening to audio recordings separately; this disconnect was challenging as I switched between programs. However, with MAXQDA I was able to import the recordings into the software, then I could transcribe straight into the program while controlling the recordings with my keyboard.

Transcribing audio-recorded interviews in the multimedia browser.

Coding Interview Transcripts

Afterward, I was able to code straight from what I had just transcribed. The automatic time stamps were also very helpful as I re-listened to recordings to ensure my transcriptions were accurate. This seamless process allowed me to perform interim coding throughout my fieldwork, which helped me identify unanticipated themes that I could probe about in future interviews. For example, themes surrounding democratic processes and how they impact health were recurring, something I had not thought about in depth before my fieldwork.

Section of transcribed text with coded segments in the left-hand column.

Preparing for the Next Steps

My first training session with my Professional MAXQDA Trainer was very informative. It allowed me to feel more comfortable exploring the software and I learned how to use the MAXQDA Web Collector browser extension. This was very helpful because there are many online newspaper articles about the topic of my project, and this function allowed me to collate and code them alongside the rest of my data. I also learned from my trainer how to use MAXMaps to visualize coded data, which I will discuss in my next fieldwork diary about analysis.

Court injunction displayed outside of the Muskrat Falls facility preventing several Land Protectors from entering the site.

Overall, using MAXQDA during my fieldwork was simple and intuitive. It allowed me to shape my project during my time in Labrador, ensuring the data I collected was rich and reflected the concerns of research participants. In my next blog post, I will discuss how I used MAXQDA in my analysis and some key findings from the project.

Editor’s Note

Jessica Penney is a recipient of the 2018 #ResearchforChange Grant. Penney is the first non-PhD level student to receive a MAXQDA Research Grant and is a MSc Global Health student at the University of Glasgow, UK. She conducted fieldwork for her research project titled “Land Protectors’ Understandings of Health in Relation to the Muskrat Falls Project and Protests” throughout the summer of 2018 in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Canada. Find out more about how she will continue to use the grant in her upcoming fieldwork diary entries, coming soon!