At the onset of the pandemic in Germany, many systems were disrupted by the closure of European borders. Among those disruptions, the agricultural industry faced major challenges in the workforce, as around 30% of agricultural workers are migrant seasonal workers who were unable to cross borders to work. To mitigate the issue of seasonal migrant workers’ immobility, the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL)[i] partnered with Maschinenringe[ii] to develop “daslandhilft”, or “the country helps”[iii] to help Germany’s farmers connect with German residents—referred to here as temporary (pandemic) workers—to help cultivate and harvest their crops. The BMEL also published a list of “systemrelevant”[iv], or essential, industries in the food sector that should remain in operation during the pandemic. This list recognizes agriculture, including specialty farms, as critically important infrastructure in Germany (BMEL 2020b). The BMEL and the BMI[v] then signed a joint agreement to allow 80,000 migrant workers to travel from Eastern Europe to German farms, promising strict COVID-19 regulations (BMEL 2020a).

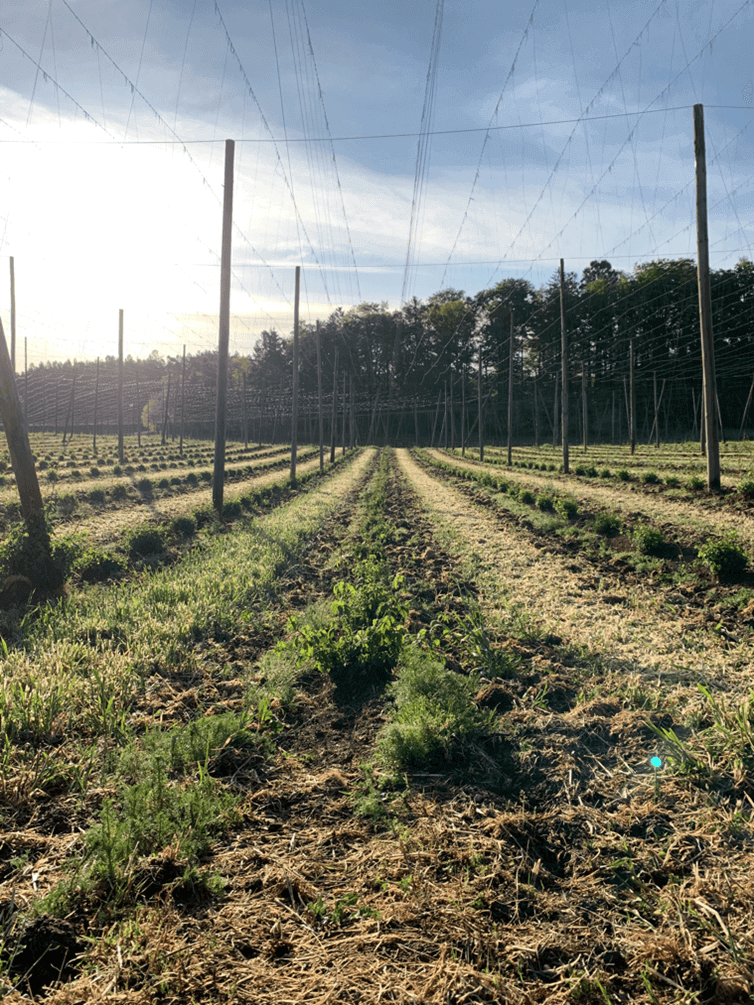

As part of “Innovation of Food, Innovation of Europe?” funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and my Consumer Science Master’s thesis at the Technical University of Munich, I conducted a one-week ethnographic study on a hops farm in the Bavarian Hallertau region. For the spring season (April-May), there are normally about 10,000 workers from Poland or Romania, but due to the pandemic, significantly fewer workers were able to enter Germany. The spring season in hops farming is the most important and labor-intensive work of the year and in 2020, German residents, through the website daslandhilft.de, stepped in to help hops farmers tend to their fields.

My research explored hops farmers’ understanding of labor and temporary workers’ understanding of agriculture by examining the treatment of migrant workers and German resident temporary workers in the context of hops farms during the first lockdown in spring 2020.

Figure 1: Hops field in Bavaria

Figure 1: Hops field in Bavaria

Field site

My data collection was based on ethnographic research, semi-structured interviews with research participants, as well as additional news and policy analysis. In response to the German government’s call, I worked on a hops farm in the Hallertau region over the course of seven days at the end of April/beginning of May 2020, with follow-up interviews until July 2020. I conducted participant observation among farmers and temporary workers on the farm, deriving fieldnotes from jottings written throughout the work day. Interviews included one with the farmer and three temporary workers on the hops farm where I worked.

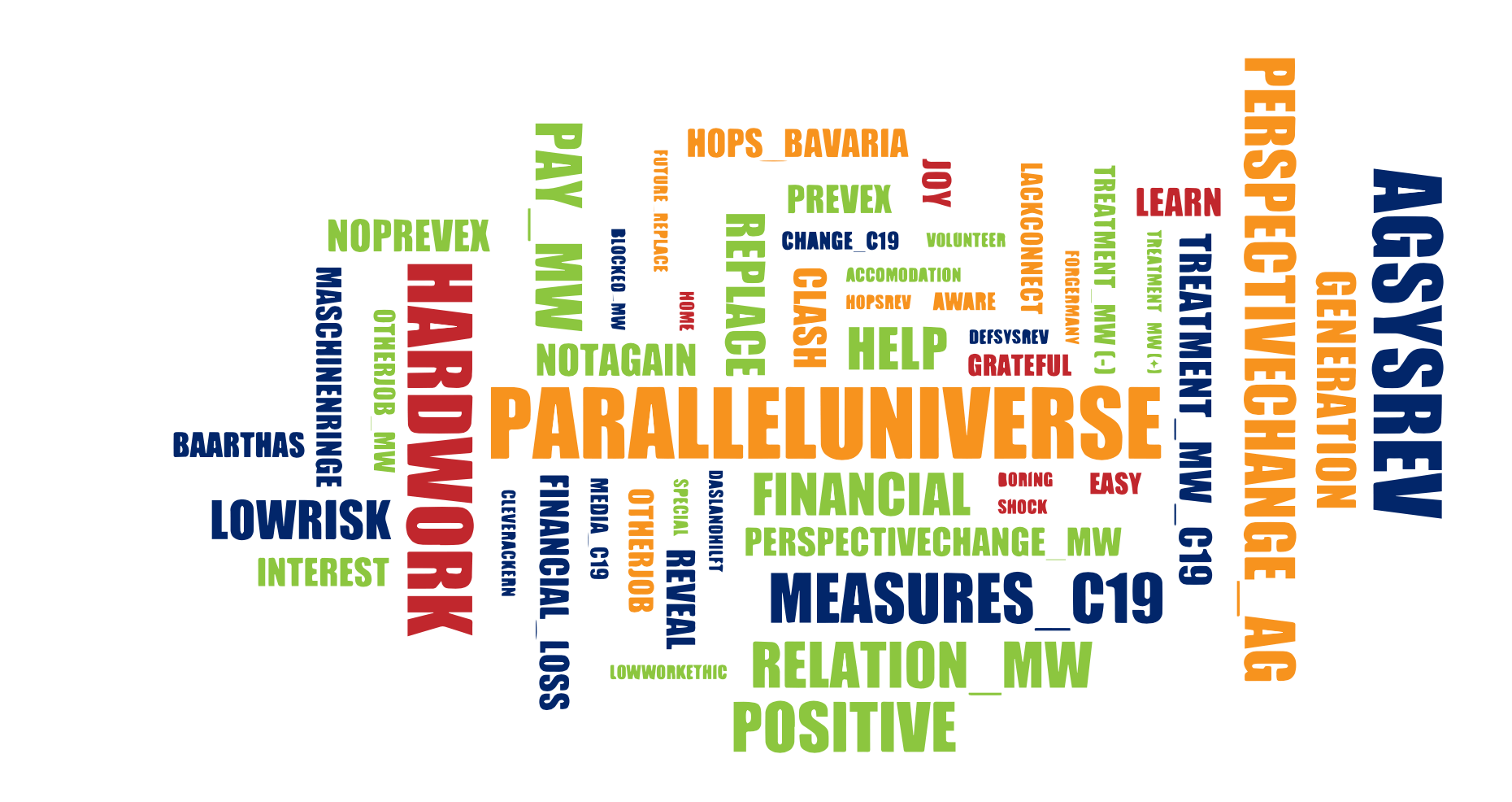

I used the MAXQDA feature code cloud to visualize which codes occurred the most. This cloud shows only which codes were most frequently applied, but not which codes interconnect and may form patterns. Therefore, I used the MAXMaps function to check the patterns I found within the codes and crosschecked this with my own pattern codes. While my previous step enabled me to understand the categorization of codes, this step helped me understand the most commonly referenced ideas.

The largest letters represent the most used codes. This enabled me to determine the most significant codes and understand the most relevant and prominent themes. After determining the parent codes, as well as the major patterns in them, I was able to define a few key findings in my data.

Findings from the Field

Figure 3: Hops field in Hallertau

Figure 3: Hops field in Hallertau

Parallel Universe (paralleluniverse)

In interviews with temporary workers, several participants mentioned the feeling of being in a “parallel universe” or “corona bubble” while working on hops farms. The ‘parallel universe’ represented a space for temporary workers to escape the pandemic and governmental regulations, allowing them to spend time outside while also earning money, both difficult in metropolitan areas during the lockdown. The hops farm as a ‘corona bubble’ likewise denoted a temporary disconnect from the globally spreading COVID-19. Yet, besides such sentiments of escapism, for temporary workers, this parallel universe also meant exposure to the realities of migrant work, and the complex social ties between seasonal migrant workers and hops farmers. Through this work, both temporary workers and farmers changed their perspectives on what constitutes German agriculture.

Treatment of Migrant Workers (All MW- migrant worker- codes)

Following the COVID-19 related death of a Romanian worker flown in to farm asparagus, questions were raised about whether migrant workers were actually granted access to health care or increased safety measures (Klawitter and Verseck 2020). Seasonal migrant workers were often not given masks, stayed in crowded housing where social distancing was impossible, and several contracted COVID-19 while on farms in Germany (Geiger 2020; Klawitter et al. 2020). In summer 2020, catastrophic working and housing hygiene conditions for migrant workers both in crop farms and the meat industry led to considerable coronavirus infection clusters. As stated by Klawitter et al. (2020, para. 12), “the coronavirus has shone a light on the precarious conditions of migrant workers, on the risk of infections in the cramped accommodations where they live and on the politicians’ lack of interest in their situation.” Temporary workers also took issue with migrant workers’ payment, which they viewed as a form of mistreatment (they were paid significantly less). Desperate to keep temporary workers on the farm for the entire time necessary, farmers paid German residents more than their migrant workers for the same work to secure their harvests.

Essential Work (All SYSREV- system relevant- codes)

During fieldwork on hops farms, not all temporary workers agreed that the ‘essential’ work of harvesting crops, like asparagus, strawberries, or hops justified flying in thousands of farm workers. Temporary workers wondered if hops were really necessary for survival, and most agreed that Germans could do without them. However, farmers and organizers claimed that hops had to be maintained annually, or the crop would be negatively impacted for years to come; farmers’ livelihoods depending on the consistent cultivation of the crop. Whether the crop itself is essential or not, without hops sales, the farmers would lose significant income. Further, no hops means no beer, which is important both to the region’s economy and Bavaria’s cultural identity. Hence, not everyone agreed on the interpretation of essential work in agriculture.

Discussion

The coronavirus pandemic showed differences regarding the value of farmers, temporary workers, and migrant workers. Migrant workers were rendered essential (flown across closed borders), replaceable (by German residents), and disposable (if infected due to a lack of appropriate health measures). Counter to media reporting and general sentiment in the public that German residents’ freedom, and mobility were curtailed, in light of migrant workers’ conditions, I propose a different interpretation. German residents who sought work and respite from their (mostly urban) confinements as a result of the pandemic and governmental regulations were free to either stay in their (safe) home, or to replace migrant workers for pay, in the outdoors. Meanwhile, migrant workers were not free to stay safe working from home due to financial necessity and the nature of agricultural work.

The coronavirus pandemic can be seen as a crisis that allowed the German government to apply flexibility to pandemic policies in order to maintain food security in Germany. More specifically, the German government’s choice to fly over 80,000 workers despite closed borders could be seen as overriding law in a lawless arena (see Agamben 2005) and limiting the rights of migrant workers. Importantly, during the pandemic, migrant workers coming to Germany were granted neither the rights of other Eastern Europeans, who were subject to strict lockdowns and COVID-19 measures, nor the rights of temporary workers in Germany, who were provided more payment and better accommodation, and stayed within the borders of their own constituency to perform field work.

The described circumstances raise the central question: who profits from migrant labor? Some temporary workers attributed Germany’s low food prices to inexpensive foreign labor, suggesting that consumers benefit most from cheap, migrant labor that guarantees affordable food in supermarkets. Temporary workers’ direct and personal experiences with agricultural work changed their preconceived notions of the workings of German agriculture. Platforms like daslandhilft.de may foster more exchange and relationships between consumers, farmers, and migrant workers both for localizing agricultural production, and for providing more adequate housing and better pay for migrant workers that want, or have to, travel to places like Germany. Ultimately, this may shift wider public debates away from currently common accusations of farmers as scapegoats for environmentally destructive wrongdoing, towards labor conditions, and how these are related to food production and consumption. In effect, one can argue that it is primarily Eastern Europeans that sustain and feed the German agricultural system and people.

Figure 4: An overgrown hops field

Figure 4: An overgrown hops field

About the Author

Marlise Schneider is a PhD candidate at the Munich Center for Technology in Society at the Technical University of Munich. She employs qualitative research methods to study technological and social innovation, agriculture, and rural studies. Her goal is to create positive change in society by centrally focusing on groups often left out of the conversation.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. State of Exception. United States of America: The University of Chicago Press.

BMEL. 2020a. ‘Konzeptpapier Saisonarbeiter in Der Landwirtschaf Im Hinblick Auf Den Arbeits-Und Gesundheitsschutz [Concept Paper on Seasonal Workers in Agriculture with Regard to Occupational Health and Safety]’. Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft.

———. 2020b. ‘COVID-19 FAQ’. Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft.

Geiger, Gabriel. 2020. ‘How Europe’s Pandemic Response Pushed Poor Migrant Workers Further Through the Cracks’. Vice World News, 18 August 2020.

Klawitter, Nils, Steffen Lüdke, Hannes Schrader, and Stavros Malichudis. 2020. ‘The Systematic Exploitation of Harvest Workers in Europe’. Der Speigel, 22 July 2020.

Klawitter, Nils, and Keno Verseck. 2020. ‘Tod eines Erntehelfers mit Corona: Besuch beim Spargelhof in Bad Krozingen’. 22 April 2020. https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/bad-krozingen-tod-eines-spargel-helfers-mit-corona-ein-leben-fuer-den-spargel-a-ff21540c-8fa9-429d-b69d-0a54cc5c3462.

Miles, Matthew B., A. M. Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Third edition. Thousand Oaks, Califorinia: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Footnotes

[i] Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft [Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture]

[ii] A colloquial translation is a “circle/association for machines,” where agricultural machinery is shared among farmers and farmer associations. This association connects farmers across Germany to share expensive machinery that would often not be affordable for individual purchase.

[iii] ‘Das Land’ here refers to Germany as a nation, although ‘Land’ can be translated to ‘countryside’.

[iv] ‘Systemrelevant’ translates to systematically relevant, or critically important infrastructures. I refer to it as ‘essential’ work.

[v] Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat [Federal Ministry of the Interior]