Qualitative research methods uncover deep insights into human experiences, behaviors, and cultures that quantitative data alone cannot reveal. This comprehensive guide covers important fundamentals of qualitative research methods, from basic concepts and data collection methods to data analysis and AI-supported analysis techniques.

1. Understanding Qualitative Research

Qualitative research aims to analyze and deeply understand the complexity of human experiences. It employs a wide range of methods and approaches designed to explore individual perceptions, personal experiences, and social contexts using non-numerical data. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on statistical patterns and correlations, the qualitative approach seeks to uncover the underlying meanings and motivations behind human behavior, emotional responses, and social phenomena.

The fundamental goal of qualitative research is to capture depth rather than breadth. While quantitative studies might survey thousands of participants to identify trends, qualitative studies typically work with smaller, purposefully selected groups to gain rich, detailed insights. This approach is particularly valuable when researching nuanced, complex, or sensitive topics where context and meaning matter more than generalizability.

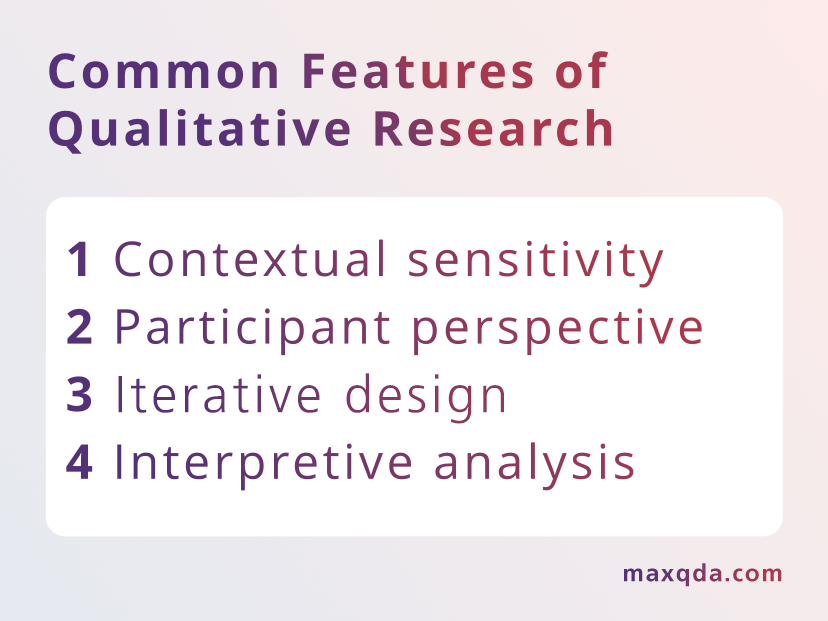

Core Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Several defining features distinguish qualitative research from other methodological approaches:

- Contextual Sensitivity: Qualitative research recognizes that human behavior and experiences cannot be fully understood without considering their environmental, cultural, and social contexts.

- Participant Perspective: Rather than only imposing predetermined categories or frameworks, qualitative research also prioritizes how participants themselves make sense of their experiences.

- Iterative Design: Qualitative research designs can adapt and evolve as new insights emerge throughout the study.

- Interpretive Analysis: Qualitative data analysis goes beyond simple description to interpret meaning, identify patterns, and develop theoretical understanding.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

Quantitative research questions focus on measuring, counting, or quantifying relationships between variables. They typically ask “how much,” “how many,” or “to what extent.” These questions seek numerical data that can be statistically analyzed to test hypotheses, identify patterns, or establish cause-and-effect relationships, for example:

- “What is the relationship between study time and exam scores among college students?”

- “How does caffeine consumption affect reaction time?”

- “What percentage of employees are satisfied with their current benefits package?”

Qualitative research questions explore experiences, meanings, perspectives, and processes that can’t easily be quantified. They typically ask “how,” “why,” or “what” in ways that seek rich, descriptive understanding rather than numerical measurement. These questions aim to understand the complexity and nuance of human behavior, social phenomena, or cultural contexts, for example:

- “How do first-generation college students experience the transition to university life?”

- “What factors influence a patient’s decision to seek mental health treatment?”

- “How do teachers adapt their instruction methods for diverse learners?”

To understand the core distinction between qualitative and quantitative research, the following comparison table presents a simplified side-by-side view of qualitative and quantitative research.

| Qualitative Research | Quantitative Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Data Nature | Words, narratives, images, observations | Numbers, measurements, statistics |

| Sample Strategy | Purposeful selection for information richness | Random selection for statistical representation |

| Sample Size | Smaller (typically 10–30 participants) | Larger (often hundreds, sometimes thousands) |

| Data Collection | Flexible, responsive, relationship-based | Standardized, controlled, instrument-based |

| Analysis Approach | Thematic coding, pattern identification, interpretation | Statistical calculations, hypothesis testing, modeling |

| Findings | Detailed descriptions, themes, theories | Statistical relationships, effect sizes, generalizations |

The Power of Qualitative Insights

Qualitative research methods excel at revealing the texture and meaning behind numerical data. For example, while a quantitative study might show that 73% of remote workers report feeling isolated, a qualitative study would explore what isolation actually feels like, how it manifests in daily life, what triggers it, and how workers develop coping strategies.

The interpretive nature of qualitative research also makes it particularly valuable for understanding diverse perspectives, uncovering hidden assumptions, and giving voice to marginalized experiences. In an increasingly complex and diverse world, these methods provide essential tools for building empathy, inclusion, and culturally responsive practices across fields from healthcare and education to business and policy development.

2. When to Use Qualitative Research

Choosing the right research approach is crucial for generating meaningful insights and actionable findings. Qualitative research methods are particularly well-suited for specific types of research questions and contexts that require deep understanding rather than broad measurement.

Typical Applications for Qualitative Research

Exploratory Research: When little is known about a topic, qualitative methods provide an excellent starting point to understand the landscape and identify key variables.

For instance, exploring how employees adapt to AI tools requires understanding their experiences and concerns before designing interventions.

Complex Human Experiences: Qualitative research excels at examining multifaceted experiences that cannot be reduced to simple variables.

For instance, healthcare researchers use these methods to understand patient experiences with chronic illness, exploring symptoms, emotional responses, family dynamics, and quality of life impacts.

Cultural and Social Phenomena: Understanding how culture shapes behavior and beliefs requires qualitative approaches that capture nuance and meaning.

For instance, researchers rely on ethnographic methods to study organizational cultures, community traditions, and social practices.

Process Understanding: When researchers need to understand how things happen over time, qualitative methods can track processes and identify turning points.

For instance, educational researchers might use case studies to understand how schools successfully implement new teaching approaches.

Decision Framework: Choose Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods are a good choice if your study addresses one or more of the following aspects:

![]() Meaning and Interpretation: You want to understand what experiences mean to participants

Meaning and Interpretation: You want to understand what experiences mean to participants

![]() Process and Context: The how and why are as important as the what

Process and Context: The how and why are as important as the what

![]() Unexplored Territory: Limited existing research or theory exists

Unexplored Territory: Limited existing research or theory exists

![]() Diverse Perspectives: You need to capture varied viewpoints and experiences

Diverse Perspectives: You need to capture varied viewpoints and experiences

![]() Complex Relationships: Simple cause-and-effect relationships are insufficient

Complex Relationships: Simple cause-and-effect relationships are insufficient

![]() Theory Development: You’re building new conceptual frameworks rather than testing existing ones

Theory Development: You’re building new conceptual frameworks rather than testing existing ones

3. Paradigms and Approaches in Qualitative Research

The methodological choices researchers make in qualitative studies are often framed with philosophical assumptions about the nature of reality, knowledge, and the research process itself. Understanding these foundations helps ensure methodological coherence and guides decision-making throughout the research process.

Philosophical Paradigms: World Views in Qualitative Research

Think of philosophical paradigms as different pairs of glasses—each lens shapes what you see and how you interpret the world around you. Your chosen paradigm fundamentally influences every aspect of your research, from the questions you ask to how you make sense of participant responses. The following table juxtaposes five widely discussed paradigms:

| Paradigm | Core Belief About Reality | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Constructivism & Social Constructionism | Reality emerges through human interactions and meaning-making processes. Multiple, valid realities exist based on individual and collective interpretations. | Focus on understanding how participants construct meaning from experiences. Emphasize participant voice and subjective understanding over objective measurement. |

| Interpretivism | Human behavior is inherently meaningful and context-dependent. Understanding requires seeing the world from participants’ perspectives. | Prioritize insider perspectives and cultural context. Use methods that capture social meanings within specific environments. |

| Critical Theory | Knowledge is never neutral—it either maintains or challenges existing power structures. Research should promote social justice and emancipation. | Examine power relations and social inequalities. Include marginalized voices. Design research that can inform social change and challenge oppressive structures. |

| Pragmatism | The value of knowledge lies in its practical utility. The best approach is whatever works to solve real-world problems. | Combine methods and paradigms as needed. Focus on actionable findings. Emphasize practical outcomes over theoretical purity. |

| Positivism & Post-Positivism | Reality exists independently of human perception. Truth can be discovered through systematic observation and measurement (positivism) or approximated through rigorous methods (post-positivism). | Seek objective patterns and causal relationships. Minimize researcher bias. Use systematic procedures to discover or approximate truth. |

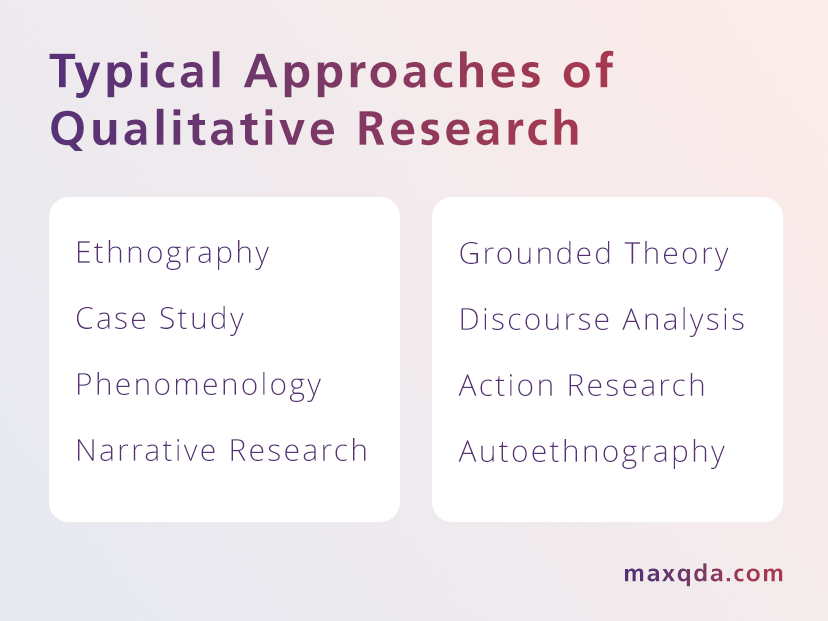

Qualitative Research Approaches

While the philosophical paradigm provides the worldview, the research approach (sometimes called a “strategy of inquiry”) determines how you’ll actually investigate your questions. A qualitative research approach represents a distinct methodological tradition that aligns with certain philosophical assumptions and specific techniques for data collection and analysis. The following “short profiles” present eight major qualitative research approaches, examining how they translate philosophical commitments into practical research strategies and methodological considerations.

Ethnography: Understanding Culture and Social Life

Ethnography involves the systematic study of people and cultures through immersive fieldwork and participant observation. Originally developed in anthropology, ethnographic methods seek to understand how groups of people live, work, and make meaning within their social contexts.

Example: A researcher studying how teachers adapt to new technology might spend a full academic year in schools, observing classroom practices, attending professional development sessions, and participating in faculty meetings to understand the complex factors that influence technology adoption.

Case Study Research: In-Depth Investigation

Case study research involves intensive investigation of a single case or small number of cases within their real-world contexts. Cases can be individuals, organizations, events, programs, or communities. The approach aims to understand complexity and uniqueness rather than generalizability.

Example: Studying how a particular school successfully increased graduation rates might involve interviews with administrators, teachers, and students; analysis of policy documents and test scores; observation of classroom practices; and examination of community partnerships.

Phenomenology: Exploring Lived Experience

Phenomenological research explores the essence of lived experience across participants who have encountered similar phenomena. Drawing from philosophical traditions, this approach seeks to understand how individuals experience and make meaning of specific phenomena in their everyday lives.

Example: Understanding the lived experience of becoming a first-time parent during the COVID-19 pandemic might involve interviewing 10-15 new parents about their experiences, emotions, challenges, and meaning-making during this unique historical moment.

Narrative Research: Understanding Through Stories

Narrative research explores how individuals construct and tell stories about their experiences, focusing on the ways people use storytelling to make sense of their lives and identities. This approach treats stories as both data and analytical focus.

Example: Understanding how cancer survivors construct meaning from their recovery might involve collecting detailed life stories that explore their life before diagnosis, their experience with treatment, and their ongoing identity and perspective on life.

Grounded Theory: Building Theory from Data

Grounded theory is an approach for developing theory that is grounded in data rather than existing theoretical frameworks. Researchers collect and analyze data in an iterative process, using constant comparison methods to develop conceptual categories eventually formed to theoretical models.

Example: Developing a theory of how individuals adapt to becoming a parent might involve interviewing diverse new parents, analyzing their strategies and decision-making processes, and building a theoretical model that explains successful adaptation patterns.

Discourse Analysis: Social Interactions and Reality Construction

Discourse analysis examines how social interactions construct realities. This approach views discourse as a dynamic and constitutive force that shapes understandings, knowledge, power relations and institutional norms rather than treating communication as a neutral tool.

Example: A researcher studying climate change communication might analyze how news outlets frame environmental issues, examining how discursive practices—including language choices, images and representations—shape public understanding and which voices are privileged or marginalized.

Action Research: Research for Social Change

Action research promotes social transformation through collaborative inquiry and direct intervention. Researchers work collaboratively with communities or organizations to identify issues, implement interventions, and evaluate outcomes through iterative cycles.

Example: A community health center experiencing high patient no-show rates might partner with patients, staff, and community members to identify barriers to attendance, pilot solutions like transportation assistance, and continuously adjust interventions.

Autoethnography: Personal Experience as Data

Autoethnography combines autobiography with ethnographic research, using the researcher’s personal experiences as primary data to understand broader cultural, social, or political phenomena. This approach explicitly embraces subjectivity and reflexivity.

Example: A researcher living with chronic illness might analyze their own medical appointments, daily symptoms, and coping strategies while connecting these personal experiences to broader research on patient-doctor relationships and healthcare accessibility.

Selecting Your Qualitative Research Approach

Choosing among these approaches requires careful consideration of your research questions, philosophical stance, available resources, and intended outcomes. Consider whether you’re most interested in culture (ethnography), experience (phenomenology), theory-building (grounded theory), specific cases (case study), stories (narrative research), change (action research), language and power (discourse analysis), or personal/cultural connections (autoethnography).

Please note that the approaches presented here are not exhaustive. Among others, additional approaches include arts-based research, which uses creative methods like photography or theater to engage diverse populations, and participatory research, which emphasizes community partnership by involving participants as co-researchers in study design and interpretation.

Many studies successfully combine elements from multiple approaches or use mixed methods to address complex research questions comprehensively. The key is ensuring methodological coherence—your chosen methods should align with your research questions and philosophical assumptions, regardless of whether they fit perfectly within established traditions.

Not Every Study Needs a Named Approach

While methodological textbooks often emphasize distinct research traditions and paradigms, the reality is that many—probably most—successful qualitative studies operate without explicit paradigmatic positioning or adherence to specific qualitative research approaches. This pragmatic orientation reflects the applied nature of much qualitative research, where the primary concern is generating meaningful insights rather than advancing methodological theory or demonstrating allegiance to particular scholarly traditions.

Rather than feeling pressure to fit into specific schools of thought, you can focus on selecting appropriate methods for your questions, maintaining analytical rigor, and generating meaningful insights for your intended audiences. This “methods over methodology” approach prioritizes practical effectiveness over theoretical purity, allowing you to combine techniques from different traditions, adapt procedures to local contexts, and maintain flexibility throughout the research process.

4. Principles of Qualitative Research Methodology

Core Methodological Principles

Qualitative research operates on several key principles that distinguish it from quantitative approaches and guide decision-making throughout the research process:

- Theories emerge from data through inductive reasoning rather than hypothesis testing.

- Research designs adapt flexibly as new insights develop during data collection and analysis.

- Phenomena are understood holistically within their full contextual environment.

- Researchers practice reflexivity by critically examining and making transparent their own influence on the process.

Quality Criteria: Ensuring Trustworthiness

Qualitative research maintains scientific rigor through distinct quality criteria that parallel but differ from quantitative standards. While quantitative research emphasizes (statistical) validity and reliability, qualitative research focuses on trustworthiness and authenticity in representing human experiences. Typically, the following qualitative quality criteria are discussed:

Credibility: “Are findings believable and accurate?”

Establish confidence that findings truly represent participants’ experiences through triangulation of multiple data sources, member checking where participants review interpretations, and peer debriefing with other researchers to challenge assumptions and blind spots. The quantitative equivalent is internal validity.

Transferability: “Can insights apply to other contexts?”

Provide rich, detailed descriptions of participants, settings, and processes that allow readers to assess applicability to their own contexts. Unlike statistical generalizability, transferability depends on contextual similarity rather than random sampling. The quantitative equivalent is external validity.

Dependability: “Is the research process consistent and trackable?”

Maintain comprehensive audit trails documenting all research decisions, methodological changes, and analytical processes. This transparency enables other researchers to understand and potentially replicate the study approach. The quantitative equivalent is reliability.

Confirmability: “Do findings reflect participant voices rather than researcher bias?”

Demonstrate clear links between data and interpretations through detailed documentation, reflexive awareness of researcher influence, and systematic analysis procedures that ground conclusions in evidence rather than assumptions. The quantitative equivalent is objectivity.

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “Qualitative research is not rigorous”

Quality qualitative research follows systematic procedures, maintains transparency, and employs various strategies to ensure credibility and trustworthiness.

Misconception 2: “Qualitative findings aren’t generalizable”

While not statistically generalizable, qualitative findings offer analytical generalizability—insights that transfer to similar contexts and populations.

Misconception 3: “Qualitative research is just opinion”

Rigorous qualitative research involves systematic data collection, analysis, and interpretation that goes far beyond personal opinion or anecdote.

5. Planning Your Qualitative Study

Successful qualitative research requires careful planning that balances structure with flexibility. Unlike quantitative studies with predetermined protocols, qualitative research planning must accommodate emergent insights while maintaining methodological rigor. This section provides a comprehensive framework for designing and preparing your qualitative study.

Defining Clear Research Goals and Questions

Effective qualitative research begins with well-crafted research questions that are open-ended, exploratory, and focused on understanding rather than proving. Strong qualitative research questions typically begin with “how,” “what,” or “why” rather than seeking to confirm hypotheses.

- “How do first-generation college students navigate academic and social challenges?”

- “What meanings do patients assign to their chronic pain experiences?”

- “Why do some organizations successfully adapt to digital transformation while others struggle?”

Beyond your primary research question, clarify what you hope to achieve. Are you building theory, informing practice, supporting policy development, or giving voice to marginalized experiences? Clear objectives guide methodological choices and help maintain focus throughout the study.

Furthermore, think about how your findings will be used. Will they inform program development, organizational change, clinical practice, or community advocacy? Understanding the intended impact helps shape your approach and ensures your research addresses real-world needs.

Decide on Data Collection Methods

Your choice of data collection methods should align directly with your research questions, participant characteristics, and practical constraints while considering what types of data will best address your research objectives. Consider whether you need in-depth individual perspectives (suggesting interviews), group dynamics and shared experiences (pointing toward focus groups), natural behaviors in context (indicating observation), or existing materials and representations (suggesting document analysis). Practical factors such as participant availability, geographic distribution, sensitivity of topics, and available resources will further guide your decisions. Most qualitative studies benefit from multiple data collection methods to capture different dimensions of the phenomenon under investigation.

Consider starting with one primary method and adding complementary approaches as your understanding of the research context develops. Chapter 6 below explores several data collection techniques in detail, providing practical guidance for implementation, benefits and challenges of each approach.

Strategic Sampling and Recruitment

Unlike random sampling used in quantitative research, qualitative studies employ purposive sampling to select participants who can provide rich, relevant insights. Common strategies include:

- Maximum Variation Sampling: Selecting participants with diverse characteristics to capture a range of perspectives

- Homogeneous Sampling: Focusing on participants with similar backgrounds to understand specific experiences deeply

- Theoretical Sampling: Selecting participants based on emerging theoretical insights during data analysis (common in grounded theory)

- Snowball Sampling: Using participant referrals to access hard-to-reach populations

Sample Size Considerations: Qualitative sample sizes are typically smaller than quantitative studies but should be sufficient to achieve data saturation—the point where new data no longer provides additional insights. Sample sizes commonly range from 5–25 participants, though the actual number varies considerably depending on study scope (undergraduate thesis versus doctoral dissertation versus large-scale research project), methodological approach (case studies may involve fewer participants studied intensively, while phenomenological studies typically require 10–15 participants), and available resources.

Recruitment Strategies: Develop multiple recruitment approaches to ensure access to appropriate participants:

- Direct outreach through professional networks or organizations

- Community partnerships with relevant groups or institutions

- Online recruitment through social media or specialized platforms

- Flyers and announcements in relevant locations

- Professional referrals from colleagues or practitioners

Logistical Planning and Resource Management

Create realistic timelines that account for the iterative nature of qualitative research. Build in flexibility for extended data collection if new themes emerge or for additional analysis time. Common phases include:

- Preparation and recruitment (2-4 weeks)

- Data collection (4-12 weeks, depending on method)

- Initial analysis (concurrent with collection)

- In-depth analysis (4-8 weeks)

- Writing and reporting (4-8 weeks)

Particularly the analysis phase may be much longer, even years, depending on the context and project requirements.

You should consider costs for transcription services, analysis software, participant incentives, travel for data collection, and potential research assistance. Many qualitative research projects require fewer financial resources than large quantitative studies but may need significant time investments.

In addition to financial resources, you’ll need to account for practical assets like recording equipment (audio/video), secure data storage systems, and qualitative data analysis software. If working with a team, ensure every member understands the methodology, ethical requirements, and their specific roles. It’s also crucial to provide training on interview techniques, observation methods, and data handling procedures to ensure consistency and rigor across the project.

Pilot Testing and Refinement

Test your data collection approaches with a small number of participants before full implementation. Pilot testing reveals practical challenges, helps refine questions or protocols, and builds researcher confidence.

Use pilot testing insights to refine your approach. This might involve adjusting interview questions, modifying observation protocols, or reconsidering recruitment strategies. Document these changes as part of your methodological audit trail.

Comprehensive Ethical Planning

Qualitative research involving human participants may require ethical review by an ethics committee. Start this process early, as reviews can take several weeks or months.

Prepare detailed protocols describing your methods, participant recruitment, data handling, and risk mitigation strategies.

Develop robust plans for protecting participant privacy, especially important in qualitative research where rich, detailed data could potentially identify individuals.

Consider pseudonyms, data de-identification procedures, secure storage systems, and limited access protocols.

Qualitative research often involves intimate sharing and relationship-building between researchers and participants.

Acknowledge potential power imbalances and develop strategies to avoid harm, ensure voluntary participation, and respect participant autonomy throughout the process.

6. Data Collection Techniques

Effective data collection forms the foundation of quality qualitative research. The techniques you choose should align with your research questions and practical constraints while generating rich, detailed data that can answer your research questions. This section explores the primary qualitative data collection techniques and provides practical guidance for implementation.

Interviews: The Heart of Qualitative Research

Qualitative interviews, which are typically conducted with a single participant (and sometimes two), represent a foundational technique for data collection. Structured interviews follow a rigid script of predetermined questions, which is useful when consistency across participants is crucial. In contrast, unstructured interviews begin with broad topics and allow the conversation to flow naturally, making them ideal for exploratory research. The most common approach is the semi-structured interview, which uses a guide of key questions but allows the flexibility to explore interesting topics that emerge during the conversation.

In addition to these standard forms, researchers may employ special interview formats for specific purposes:

- Life history interviews, for instance, capture comprehensive personal narratives over multiple sessions.

- Photo-elicitation interviews use photographs to stimulate discussion and memory, while

- walk-and-talk interviews combine movement with conversation, a technique particularly useful for understanding spatial experiences.

Successful interviewing requires preparation, skill, and sensitivity. Begin with easy, descriptive questions before moving to more complex or sensitive topics. Use open-ended questions that encourage detailed responses rather than yes/no answers. Practice active listening, allow for silence, and follow up on interesting points with probes like “Can you tell me more about that?” or “What was that experience like for you?”

Effective interviews depend on establishing comfortable relationships with participants. Share something about your background and your research interests, explain how the information will be used, and respect participants’ boundaries. Create safe spaces for sharing by demonstrating genuine interest and maintaining confidentiality.

Focus Groups: Harnessing Group Dynamics

Focus groups bring together a short group of participants (ca. 6–10) to discuss specific topics through facilitated group discussion. The moderator guides conversation using predetermined questions while encouraging interaction among participants. Group dynamics often generate insights that individual interviews cannot capture.

You should consider whether to use homogeneous groups (similar backgrounds) or heterogeneous groups (diverse backgrounds), depending on the research interest. Homogeneous groups may encourage open sharing on sensitive topics, while diverse groups can reveal different perspectives and potential conflicts.

Moderating a focus group may be challenging, because skilled facilitation ensures balanced participation while managing dominant personalities and encouraging quieter participants. You can use techniques like round-robin sharing, small group discussions, and written exercises to include all voices; and you may address disagreements constructively, as they often reveal important insights.

Observation Methods: Seeing Social Life

Observation methods offer researchers direct access to naturally occurring behaviors and social interactions in their authentic contexts.

- In participant observation, researchers join the activities they’re studying while simultaneously documenting what they see, providing insider perspectives and access to behaviors that participants might not describe in interviews.

- Non-participant observation takes a different approach, with researchers maintaining distance while observing, potentially seeing patterns that participants themselves might miss. This approach works particularly well in public settings or when participation might disrupt natural activities.

Reflect about the needed degree of structuring the observation. For more systematic data collection, structured observation uses predetermined categories or checklists to record specific behaviors or interactions, though this approach may miss unexpected phenomena that emerge during fieldwork.

Regardless of the observational approach chosen, detailed field notes remain essential for capturing observations, conversations, impressions, and reflections. Successful fieldwork requires developing systems for recording different types of information, including descriptive notes that document what happened, reflective notes that capture your thoughts and interpretations, and methodological notes that track decisions about the research process.

Document and Media Collection

Document and media collection allows you to gather existing materials that provide insights into official perspectives, public discourse, and cultural representations without requiring direct participant interaction. Qualitative researchers can collect diverse materials including organizational documents, policy papers, social media posts, websites, photographs, videos, artwork, and historical records. The key lies in selecting documents that relate directly to your research questions while considering their purpose, audience, and context.

Visual and Creative Data Collection Methods

Visual and creative methods expand the possibilities for data collection beyond traditional verbal approaches, offering participants alternative ways to express their experiences.

- Photo-voice and visual storytelling techniques involve participants creating photographs or other visual materials to document their experiences, which are then discussed in interviews or focus groups. This approach works particularly well with communities where verbal expression may be challenging or where visual representation adds crucial dimensions that words cannot capture.

- Participatory visual methods such as mapping exercises, drawing activities, and collage creation help participants express complex ideas and emotions that might be difficult to articulate verbally. These techniques prove especially valuable when working with children, conducting cross-cultural research, or exploring sensitive topics that require alternative forms of expression.

Video and audio recording can enhance any of these approaches by allowing detailed analysis of both verbal and non-verbal communication, though they require careful attention to consent, privacy, and data storage considerations. When using recording equipment, you should consider its potential impact on participant behavior and focus on building rapport before introducing recording devices into the research setting.

Digital and Technology-Enhanced Collection

Digital technologies have revolutionized qualitative data collection by enabling more flexible and comprehensive approaches to gathering research data. Mobile data collection through smartphones and tablets allows real-time documentation and immediate upload to secure servers, with specialized apps facilitating diary studies, experience sampling, and location-based data collection.

Online interview platforms using video conferencing tools have expanded access to geographically dispersed participants while presenting new considerations for rapport-building, technical difficulties, and privacy. Successful online collection requires backup plans for technical issues and potential technical support for less digitally comfortable participants.

Modern qualitative research increasingly involves multiple data types collected across different platforms. Early planning for data integration is essential, ensuring compatibility between collection methods and analysis software to prevent challenges during the analysis phase.

Tip: Establish secure systems for data storage, transmission, and access from the beginning. You may use encryption for digital files, secure physical storage for hard copies, and ensure limited access protocols for research team members.

Data Collection Techniques Comparison

| Method | What is it? | Typical Use Cases | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | One-on-one or one-one-two conversations (structured, semi-structured, or unstructured) | Personal experiences, complex topics, individual perspectives, life histories | Time-intensive, requires skilled interviewing, potential researcher bias |

| Focus Groups | Facilitated group discussions with ca. 6–10 participants | Social dynamics, shared experiences, diverse perspectives, community issues | Requires skilled moderation, dominant personalities, some may not share openly |

| Observation | Watching and documenting behaviors in field settings (participant or non-participant) | Natural behaviors, social interactions, contextual understanding, organizational culture | Time-consuming, access challenges, observer effect, potential bias, |

| Document and Media Collection | Gathering existing materials (policies, media, social media, archival data) | Official perspectives, public discourse, cultural representations, historical analysis | Limited to existing materials, potential bias in sources, context may be unclear |

| Visual and Creative Data Collection | Photo-voice, mapping, drawing, video recording for participant expression | Communities with limited verbal expression, cross-cultural research, sensitive topics | Requires technical skills, interpretation challenges, consent complexities |

| Digital Methods | Mobile apps, online platforms, social media collection, video conferencing | Geographically dispersed participants, real-time data, diary studies, digital cultures | Technical difficulties, digital divide, privacy concerns, rapport-building challenges |

7. Data Analysis Methods

When analyzing qualitative data, researchers distill rich and often layered material into structures, meanings, and insights that help answer the research question. Unlike quantitative analysis with standardized statistical procedures, qualitative analysis is interpretive, iterative, and requires researchers to make numerous decisions about coding, categorization, and meaning-making. This section explores major approaches to qualitative data analysis and provides practical guidance for implementation.

Please note: Some of the presented analysis methods are inherently tied to specific methodological and philosophical frameworks outlined previously:

- grounded theory,

- discourse analysis,

- and narrative analysis.

However,

- thematic analysis

- and qualitative content analysis

serve as flexible analytical methods that can be applied effectively across diverse research approaches and paradigmatic orientations.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is a widely used qualitative analysis method, suitable for most qualitative research questions and compatible with various theoretical frameworks. The approach involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data while maintaining flexibility in theoretical and epistemological approaches.

Braun and Clarke’s influential framework outlines six phases of thematic analysis:

- Familiarization: Reading and re-reading data, noting initial ideas and patterns

- Initial Coding: Generating systematic codes that identify interesting features

- Theme Development: Collating codes into potential themes and gathering supporting data

- Theme Review: Checking themes against coded extracts and the entire dataset

- Theme Definition: Refining themes and developing clear names and definitions

- Report Writing: Producing the final analysis with compelling examples

Inductive thematic analysis (which is most common) allows themes to be developed from the data without predetermined theoretical frameworks, while deductive analysis uses existing theories or concepts to guide theme development. Many researchers combine both approaches throughout the analysis process.

To ensure rigor, you should maintain detailed records of coding decisions, work with multiple analysts when possible, and regularly return to raw data to verify theme development.

Qualitative Content Analysis

This also widely applied method is used to systematically analyze textual, visual, or audio content to identify patterns, themes, and meanings within the data. Unlike quantitative content analysis that focuses on frequency counts, qualitative content analysis emphasizes context, latent meanings, and interpretive understanding.

Kuckartz’ and Rädiker’s approach to structuring qualitative content analysis proceeds in seven phases:

- Initial work with the text: Read, write memos and case summaries

- Develop main categories: Create overarching analytical categories

- First coding cycle: Code data with main categories (case by case)

- Develop sub-categories: Create detailed sub-categories inductively

- Second coding cycle: Code data with sub-categories (main category by main category)

- Analyze the coded data: Perform simple and complex analyses

- Write up results: Document findings and analytical process

Qualitative content analysis works particularly well for analyzing interviews, documents, media representations, social media posts, organizational communications, and any form of recorded communication. Researchers use this method to study everything from news coverage of social issues to patient narratives in healthcare settings. The method integrates easily with quantitative research in mixed methods projects and can be applied within various research approaches including case studies, ethnography, and discourse analysis.

Grounded Theory Analysis

Originally developed by Glaser and Strauss, grounded theory emphasizes building explanatory theories that are “grounded” in empirical data rather than testing existing theories. Within the overall approach of grounded theory, specific analysis techniques for generating theory from data are offered:

- Constant Comparative Method: Continuously comparing incidents, codes, and categories within and across data sources to identify patterns and relationships

- Coding Process: Moving through multiple levels of abstraction from initial/open coding (line-by-line analysis) to focused/axial coding (developing categories) to theoretical/selective coding (integrating categories around a core concept)

- Theoretical Sampling: Strategically selecting additional data sources based on emerging analytical insights to develop and refine theoretical categories

- Memo Writing: Maintaining detailed analytical notes throughout the process to capture theoretical insights, relationships between categories, and methodological decisions

- Creating Diagrams: Visual representations of categories, relationships, and theoretical concepts that support analysis and clarify complex connections. Diagrams help identify key categories, reveal interconnections, and structure the emerging theory.

Grounded theory analysis works particularly well for exploring social processes, understanding how people navigate complex situations, and developing explanatory frameworks for understudied phenomena.

Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis is both a broad research approach (as introduced above) and a specific analytical method for examining how language constructs meaning, identity, and social reality. It works from the premise that language is not a neutral tool for communication but actively shapes our understanding of the world and the power relations within it.

Different analytical traditions have developed distinct emphases:

- Conversation Analysis focuses on the micro-level structure and sequential organization of naturally occurring talk, examining turn-taking, pauses, and repair mechanisms

- Critical Discourse Analysis investigates how language use reproduces or challenges power relations, ideologies, and social inequalities at a macro level

- Foucauldian Discourse Analysis examines how historically situated discourses shape what can be known, said, and done within particular contexts

In a discourse analysis, researchers examine word choices, metaphors, narrative structures, and rhetorical strategies. They pay attention to what is said and not said, how speakers position themselves and others, and how language reflects or challenges dominant narratives.

Discourse analysis is valuable for studying political communication, media representations, organizational language, therapeutic conversations, and any context where language use reveals important social or cultural dynamics.

Narrative Analysis

The narrative research approach outlined above treats stories as both the data for analysis and a fundamental way humans organize and make sense of their experience. Rather than breaking narratives into discrete themes, narrative analysis preserves the integrity of the story, examining how individuals construct meaning through the structure, content, and performance of their storytelling. The analysis focuses on the interplay between the plot of the story and the narrator’s interpretation.

In practice, narrative analysis examines several interconnected dimensions of a story:

- Structural and Content Analysis: Researchers analyze core story elements such as setting, characters, plot development, climax, and resolution. Attention is given to how the narrator organizes sequences of events and establishes causal relationships to create a coherent account.

- Performance and Functional Analysis: This dimension focuses on how the story is told. It considers the audience, the narrator’s performance of their identity, how they position themselves and others within the story, and the social function the storytelling is meant to achieve.

- Thematic and Holistic Analysis: While respecting the uniqueness of each story, researchers can also identify recurring themes or story types across a dataset. This approach balances the identification of broader patterns with a deep respect for each narrative’s individual coherence and context.

Narrative analysis works well for life history research, identity studies, trauma and recovery research, and any context where storytelling provides important insights into experience and meaning-making.

Practical Considerations for Analysis

Qualitative data analysis software like MAXQDA supports the analysis methods described in this chapter (as well as many other analysis methods). The software helps researchers manage large datasets, organize codes, visualize relationships, and maintain quality and rigor. However, it’s essential to remember that software facilitates rather than replaces your analytical thinking—the interpretive work remains fundamentally human.

Viewing writing as an integral part of analysis rather than simply a reporting mechanism can significantly enhance analytical depth. Beginning analytical memos early in the process and continuing to write throughout analysis often reveals new insights and connections that might otherwise remain hidden, as the act of articulating thoughts frequently generates fresh understanding of the data.

8. AI-Enhanced Qualitative Research

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming qualitative research practices, offering new tools for data collection, management, and analysis while raising important questions about the role of human interpretation in understanding social phenomena. This emerging field presents exciting opportunities alongside methodological and ethical considerations that researchers must carefully navigate.

Current AI Applications in Qualitative Research

Modern AI technologies are transforming qualitative research workflows by automating routine tasks and providing intelligent assistance throughout the analytical process:

- Automated transcription services have revolutionized the time-intensive process of converting audio recordings to text, with current AI-powered tools achieving 90-95% accuracy for clear recordings and dramatically reducing transcription time and costs. Researchers must still review and correct transcripts, particularly for interviews with accents, technical terminology, or multiple speakers, ensuring that nuanced meanings and cultural expressions are accurately captured.

- Developing codes and categories has been transformed by AI systems that can suggest initial codes for qualitative data, helping researchers identify potential patterns and themes. These tools also recommend subcategories and hierarchical structures to further differentiate main codes, enhancing analytical organization.

- Applying codes and categories becomes more efficient with AI offering intelligent suggestions for assigning existing codes to documents or text segments. These systems rapidly scan datasets and propose relevant code applications based on given code definitions, accelerating the coding process while researchers maintain final control over coding decisions.

- Text summarization allows researchers to quickly generate overviews of lengthy interviews, focus group transcripts, or document collections, providing efficient ways to identify key content areas for deeper analysis.

- Interactive data exploration through dialogical AI chat interfaces enables researchers to engage dynamically with their datasets, asking questions about patterns, relationships, and meanings within selected text portions or entire documents.

- Additional supporting features include translation of selected text portions for multilingual research projects, explanations of unknown terms, and assistance with identifying relevant quotes and examples for reporting purposes.

Best Practices for AI Integration

- Intentional Integration and Planning. AI use should be purposefully integrated into research design. Researchers need to make deliberate decisions about where, when, and how AI tools will support their analytical process, with clear rationale for these choices and reflection on how AI integration aligns with their methodological approach.

- Maintaining Human Judgment and Critical Oversight. Researchers need to maintain critical oversight, using AI suggestions as starting points or source of inspiration for deeper human interpretation rather than final analytical conclusions. Researchers should establish clear protocols for when to accept, modify, or reject AI suggestions, ensuring that the interpretive depth and contextual sensitivity that define quality qualitative research remain central to the analytical process.

- Maintaining Transparency. Comprehensive documentation of AI tool usage in methodology sections is essential for maintaining research credibility and supporting reproducibility. This includes recording specific software versions, AI settings, the extent of AI involvement in different analytical phases, and detailed descriptions of how AI-generated outputs were verified, modified, or integrated with human analysis.

- Maintaining Quality. Regular checks of AI outputs against raw data ensure accuracy and relevance while maintaining the integrity of participant voices and meanings. Develop systematic processes for reviewing and refining AI-generated codes, themes, or summaries, treating them as preliminary drafts that require human validation rather than final products.

- Developing AI Literacy. Researchers should cultivate comprehensive AI literacy, including skills in crafting clear, specific prompts and the ability to critically evaluate AI outputs. This involves understanding AI capabilities and limitations, recognizing potential biases in AI-generated content, and knowing when to rely on or question AI suggestions to maintain analytical quality.

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Despite significant advances in AI capabilities, current systems still may struggle with cultural nuances, implicit meanings, and contextual understanding that are central to qualitative research. Researchers must carefully evaluate whether AI interpretations adequately capture the cultural and social dimensions essential to their studies, particularly when working with diverse populations or sensitive topics.

AI systems can perpetuate biases present in their training data, potentially skewing analysis in subtle but significant ways. Researchers should implement systematic checks to ensure diverse perspectives are represented in AI-assisted analysis, while also recognizing that AI tools can help identify and reduce their own analytical biases by highlighting overlooked patterns.

Over-reliance on AI pattern recognition risks diminishing the creative and intuitive dimensions that make qualitative research valuable for generating unexpected insights. Researchers should maintain space for intuitive analysis and serendipitous discoveries.

Ethical considerations require careful attention to participant consent for AI analysis and data privacy protection. Researchers must ensure participants understand how their data will be processed and implement privacy-protective measures such as zero-retention policies when using cloud-based services.

9. Software Tools

Modern qualitative research increasingly relies on specialized software tools to manage, analyze, and visualize datasets. While technology cannot replace the interpretive skills central to qualitative inquiry, the right tools can dramatically improve efficiency, organization, and analytical depth.

MAXQDA: Comprehensive Qualitative Analysis Software

MAXQDA stands out as one of the most comprehensive qualitative data analysis software packages available, trusted by researchers all over the world. The platform supports the complete research process from data organization through final reporting, handling text, audio, video, and image data within a single interface.

MAXQDA’s coding system allows for complex hierarchical structures, in-vivo coding, and collaborative coding across research teams. The software’s Visual Tools create compelling charts, word clouds, concept maps, and other visualizations that help identify patterns and communicate findings effectively. The Mixed Methods tools integrate qualitative and quantitative data seamlessly.

MAXQDA’s AI Assist functionality includes automated transcription, intelligent coding suggestions, and text summarization capabilities. These features maintain researcher control while accelerating routine tasks. Researchers can accept, modify, or reject AI outputs based on their analytical judgment.

Getting Started with MAXQDA

Free Trial and Learning: MAXQDA offers a comprehensive 14-day free trial that provides access to all features without limitations. This allows researchers to test the software with their own data and evaluate its fit for their specific needs.

Training: MAXQDA provides extensive training through webinars, video tutorials, and comprehensive documentation. You may begin with this Getting Started Video:

Community: MAXQDA maintains an active network where users share innovations, discuss analytical approaches, and exchange practical insights about using the software.

Practical Case Studies: The Practice of Qualitative Data Analysis Volumes 1 and 2 present real-world research examples across different fields, showing how various researchers apply MAXQDA to address diverse research questions and apply different qualitative methods:

Essential Learning Resources

Several key publications provide comprehensive guidance for qualitative research using MAXQDA:

Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA

by Kuckartz & Rädiker offers a comprehensive textbook on the wide range of MAXQDA features

Access via Springerlink

Focused Analysis of Qualitative Interviews with MAXQDA

by Rädiker & Kuckartz provides step by step guidance on analyzing interviews

Free Download via MAXQDA Press

10. Conclusion

Qualitative research methods offer unparalleled power for understanding the complexities of human experience, social relationships, and cultural phenomena. From exploring individual lived experiences through phenomenology to understanding organizational cultures through ethnography, qualitative approaches provide essential tools for generating insights that quantitative methods alone cannot capture.

The landscape of qualitative research continues to evolve with technological advances, particularly in AI-enhanced analysis and digital data collection methods. However, the fundamental strengths of qualitative inquiry—its emphasis on meaning, context, and human interpretation—remain as relevant as ever. Success in qualitative research lies in thoughtfully combining traditional methodological rigor with modern technological capabilities.

Whether you’re a student conducting your first qualitative study, an experienced researcher exploring new methods, or a practitioner seeking to understand complex social phenomena, the approaches and techniques outlined in this guide provide a comprehensive foundation for meaningful inquiry. The key is selecting methods that align with your research questions, maintaining ethical standards throughout the process, and leveraging appropriate tools to support rather than replace human insight and interpretation.

Ready to begin your qualitative research journey? Start your free MAXQDA trial today and discover how modern software can support rigorous, insightful qualitative research while maintaining the interpretive depth that makes this approach so valuable for understanding our complex social world.

Textbooks on Qualitative Research Methods

For researchers seeking to deepen their understanding of qualitative research methods, the following textbooks offer valuable insights and practical guidance.

General Textbooks

- An Introduction to Qualitative Research by Uwe Flick – A comprehensive textbook that covers the entire qualitative research process, from theoretical foundations and research design to data analysis and quality assessment.

- Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches by John W. Creswell & Cheryl N. Poth – Presents a detailed comparison of five major qualitative approaches: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study.

- 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher by John W. Creswell & Johanna Creswell-Baez – A practical, skills-based guide that breaks down the qualitative research process into 30 distinct steps, from writing a purpose statement to publishing findings.

Data Analysis

- Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook by Matthew B. Miles, A. Michael Huberman, & Johnny Saldaña – A foundational and comprehensive sourcebook, renowned for its practical approach and its extensive coverage of methods for displaying and interpreting data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies by Pat Bazeley – Offers hands-on guidance for the entire qualitative analysis process, from early planning to writing up findings, with strategies that integrate well with qualitative analysis software.

- The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers by Johnny Saldaña – An essential guide that provides a comprehensive overview of various coding methods, offering detailed examples and practical advice for applying them to your data.

- Analyzing Qualitative Data by Graham R. Gibbs – A practical, introductory guide to the core techniques of qualitative data analysis, explaining how to manage, code, and interpret qualitative data.

Specific Analysis Approaches and Methodologies

Thematic Analysis:

- Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide by Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke (2022) – The definitive guide to thematic analysis from the scholars who developed and popularized the method, this book offers a highly accessible and practical discussion of conducting reflexive thematic analysis.

- Essentials of Thematic Analysis by Gareth Terry & Nikki Hayfield – A concise and accessible introduction that provides a clear, step-by-step framework for conducting thematic analysis, making it ideal for students and those new to the method.

Qualitative Content Analysis:

- Qualitative Content Analysis: Methods, Practice and Software by Udo Kuckartz & Stefan Rädiker – Explores different variants of qualitative content analysis giving practical examples, particularly for inductively and deductively developing analysis categories, while considering utilization of analysis software like MAXQDA.

Grounded Theory:

- Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory by Juliet Corbin & Anselm Strauss – A foundational guide to the approach of grounded theory of Strauss and Corbin, detailing systematic techniques for data analysis.

- Constructing Grounded Theory by Kathy Charmaz – A foundational text that guides researchers through the principles and practices of the grounded theory methodology, from data collection to theory generation.

Discourse Analysis:

- An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method by James Paul Gee – A foundational text that provides a clear and accessible introduction to discourse analysis, outlining Gee’s theoretical framework and practical tools for analysis.

- How to do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction by David Machin & Andrea Mayr – This book offers a practical, hands-on guide to conducting critical discourse analysis, with a focus on multimodal texts and the relationship between language, power, and ideology.

Narrative Analysis:

- Essentials of Narrative Analysis by Ruthellen Josselson & Phillip L. Hammack – Part of the “Essentials of Qualitative Methods” series, this book introduces narrative analysis as a method for understanding how people make meaning of their lives through stories.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA):

- Essentials of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis by Jonathan A. Smith – A concise, practical guide, offering an introduction to the theory and practice of conducting an IPA study.