Can word frequency analysis actually reveal anything meaningful in qualitative research? If you’re instinctively skeptical, you’re not alone.

Counting words, which is what word frequency analysis is at its core, might first seem at odds with the interpretive spirit of qualitative analysis. But when you’re buried in dozens of transcripts, hundreds of policy documents, or thousands of online comments, it’s easy to lose sight of the forest for the trees. Word frequency analysis provides a way to zoom out, mapping recurring language, surfacing hidden themes, and identifying which parts of your data warrant a closer examination.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through how to use MAXQDA’s Word Frequencies tool effectively. With real-world examples drawn from common research scenarios, you’ll see how word frequency analysis can support a more exploratory and reflective workflow.

How to Use This Guide

- Get a quick overview of what the Word Frequencies tool does and why it’s worth adding to your workflow.

- Follow the steps in running a word frequency analysis to set up and run your own counts.

- Jump to interpreting results to turn the numbers into insights.

- Pick up time-saving tips in quick actions in the results table to work smarter with your results.

- Browse use cases for real-world application examples to get inspired.

- Dig into advanced features like Dictionaries and Go Word Lists for more targeted analysis.

- Check reading beyond the numbers for common pitfalls and reflexive practices to keep your findings meaningful.

- Skip to in a nutshell for the short version if you just want the key takeaways.

1. What MAXQDA’s Word Frequencies Tool Does

MAXQDA includes a dedicated Word Frequencies tool as part of the MAXDictio module. This feature scans selected texts, counts distinct words, and presents a sortable table showing the frequency of each word’s appearance. It’s flexible enough to handle interviews, focus groups, field notes, social media downloads, policy documents, spreadsheets, and more.

In short: you choose your data, run the tool, and instantly see which words dominate your dataset, how often they appear, and where they occur. Best of all, it’s all done through an intuitive point-and-click interface.

2. Running a Word Frequency Analysis in MAXQDA

Once you’re ready to try word frequency analysis for yourself, go to MAXDictio › ![]() Word Frequencies. Additionally, you can click on the Word Frequencies label in the MAXDictio menu to only count words that appear in a Dictionary or a Go Word List, these options are explained later in the post.

Word Frequencies. Additionally, you can click on the Word Frequencies label in the MAXDictio menu to only count words that appear in a Dictionary or a Go Word List, these options are explained later in the post.

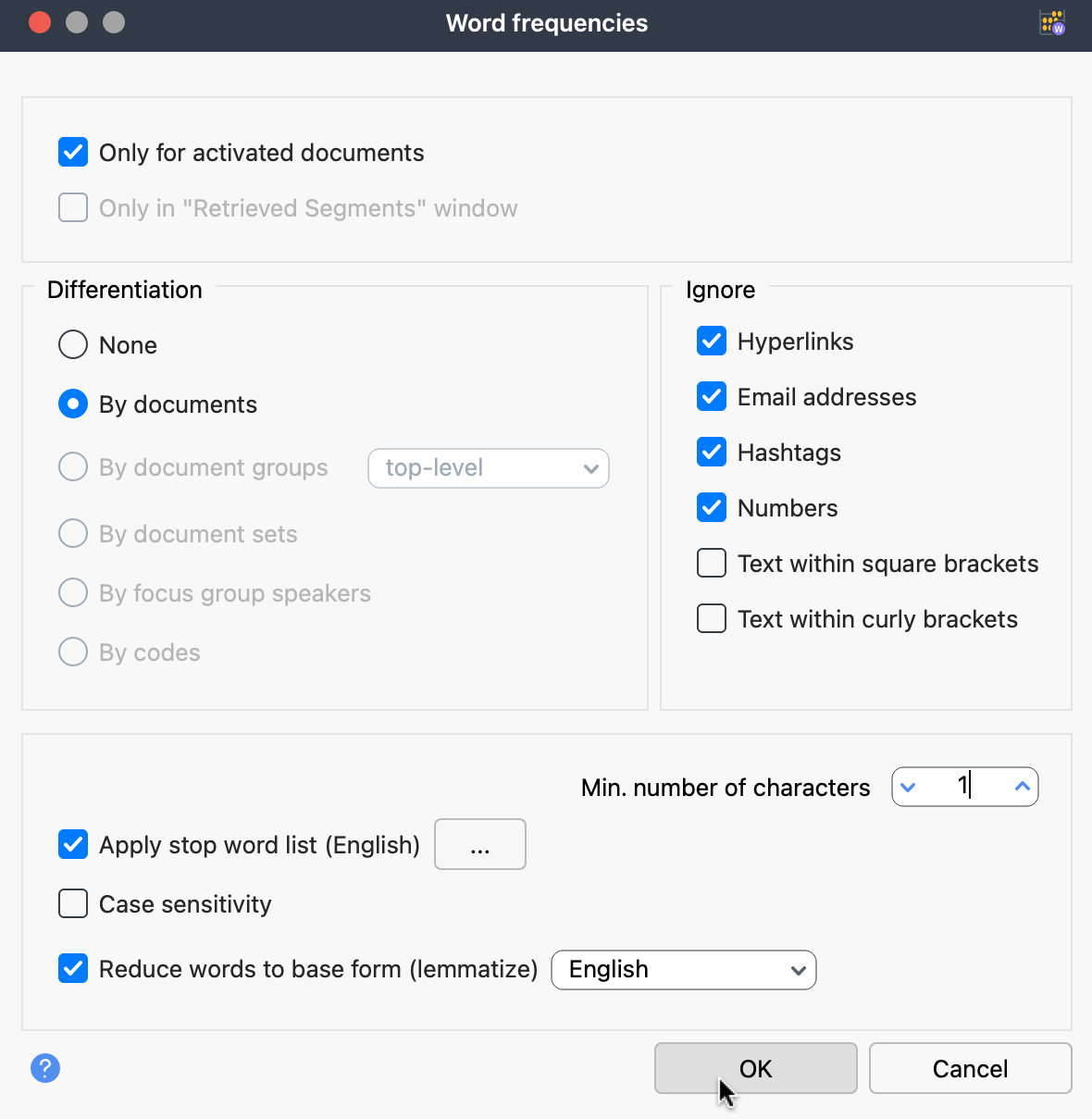

Once you start the tool, the Word Frequencies options window will appear (as shown below), where you can set up the analysis to fit your project needs.

To run a word frequency analysis, follow these steps:

a. Choose What to Analyze

Define the scope of your word count before you begin.

- Activated documents: Focus on specific files, like interviews from junior participants or job ads only from startups.

- Retrieved Segments: Analyze only coded segments currently displayed.

- All documents: If no filters are set, MAXQDA includes everything.

- Ignore elements: Use checkboxes to exclude links, emails, or other noise, especially useful in web data or exported transcripts.

This step helps you measure what matters and avoid unintended noise.

Reflexivity check

On Scope:

Activating only certain files reflects a theoretical choice. Make sure your scope aligns with the research question, not convenience. Write one sentence in your memo about why these documents are in, and why others are out.

b. Compare Across Groups

Choose how to break down word counts across different parts of your project.

- By documents: Spot outliers or files driving specific terms.

- By document groups or sets: Compare groups like “Wave 1 Interviews” or “Participants Under 30.”

- By focus group speakers: Contrast roles or participants (visible only in focus group data).

- By codes: Explore language used in specific themes or analytical categories (available when analyzing retrieved segments).

These breakdowns reveal patterns that are not visible in an aggregate view.

c. Fine-Tune the Output

Control how words are counted so the results align with your research question.

- Minimum characters: Ignore short filler words (e.g., set a 4-character minimum to skip “the” or “and”).

- Stop word list: Apply or create a list to remove common but irrelevant words (like “team” in job ads or “section” in legal text).

- Case sensitivity: Count “Research” and “research” separately if needed, important for proper nouns and acronyms.

- Lemmatization: Decide whether to group word variants (e.g., “gave,” “given,” “gives” → “give”) or keep them distinct. Helpful when deciding between general trends and nuanced differences.

With these settings in place, your output may be cleaner and easier to interpret.

Reflexivity check

On Lemmatization:

Grouping forms like “regulate,” “regulated,” and “regulation” changes meaning in legal or policy texts. Ask: are these forms conceptually linked in your context, or should they be treated separately? Note your choice down in your project memo.

On Stop Words:

Stop Word Lists are not neutral. Removing frequent but “uninformative” words may shape what patterns become visible. Document what you removed and why, then rerun once with and once without the stop word list to see what changes and how.

3. Interpreting the Word Frequency Analysis Results

Now for the fun part: making sense of what shows up and using it to guide your analysis.

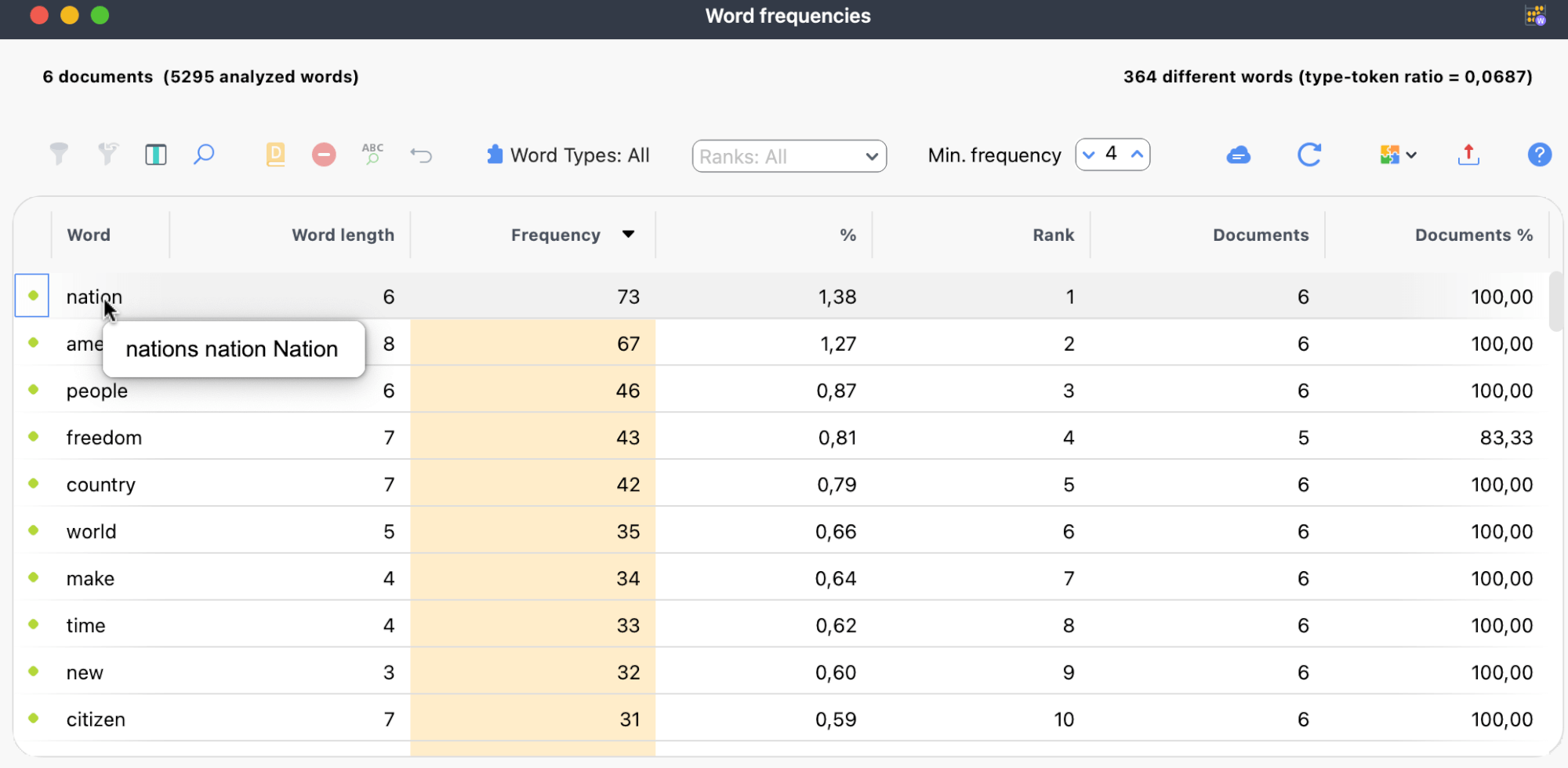

When you click OK, MAXQDA processes the data and generates a Word Frequencies table.

Top bar

The top part of the window summarizes scope and size: number of documents analyzed, total words parsed, number of unique words, and the type-token ratio (unique words ÷ total words; a rough measure of lexical diversity that is sensitive to text length) Learn more in the MAXQDA manual.

Table Columns

You will typically see these columns: Word, Word length, Frequency, % of total, Rank, Documents, and Documents % (the set of columns varies by your analysis settings). Right-click the header row to manage column display.

Tip

If lemmatization is enabled, hovering over a word reveals its grouped variants, as shown in the image above. For merged terms, a ![]() icon appears and hovering over the row shows which terms were combined.

icon appears and hovering over the row shows which terms were combined.

Here are strategies for making sense of the numbers:

- Look for Dominant Terms and Recurring Themes

High‑frequency words can signal central topics, cultural keywords, or repeated concerns. In job advertisements, you might notice terms like “team,” “flexibility,” or “benefits.” In interview transcripts, participants may frequently mention “trust,” “fairness,” or “stress.” These counts highlight where the discourse gravitates but to understand why, you still need to read the surrounding segments. Use word frequencies as entry points for deeper reading, not as standalone conclusions. - Compare Across Groups and Codes

When you choose to differentiate results, MAXQDA displays how often each word appears across documents, groups, sets, or coded segments. This lets you compare language use between subgroups or themes. For example, in a focus group study, you might differentiate by speaker to compare participants’ vocabulary. In policy research, differentiation by chapter codes can show which sections emphasize specific concepts. These breakdowns reveal variations that might not surface in aggregate counts. - Use Frequencies to Guide Coding

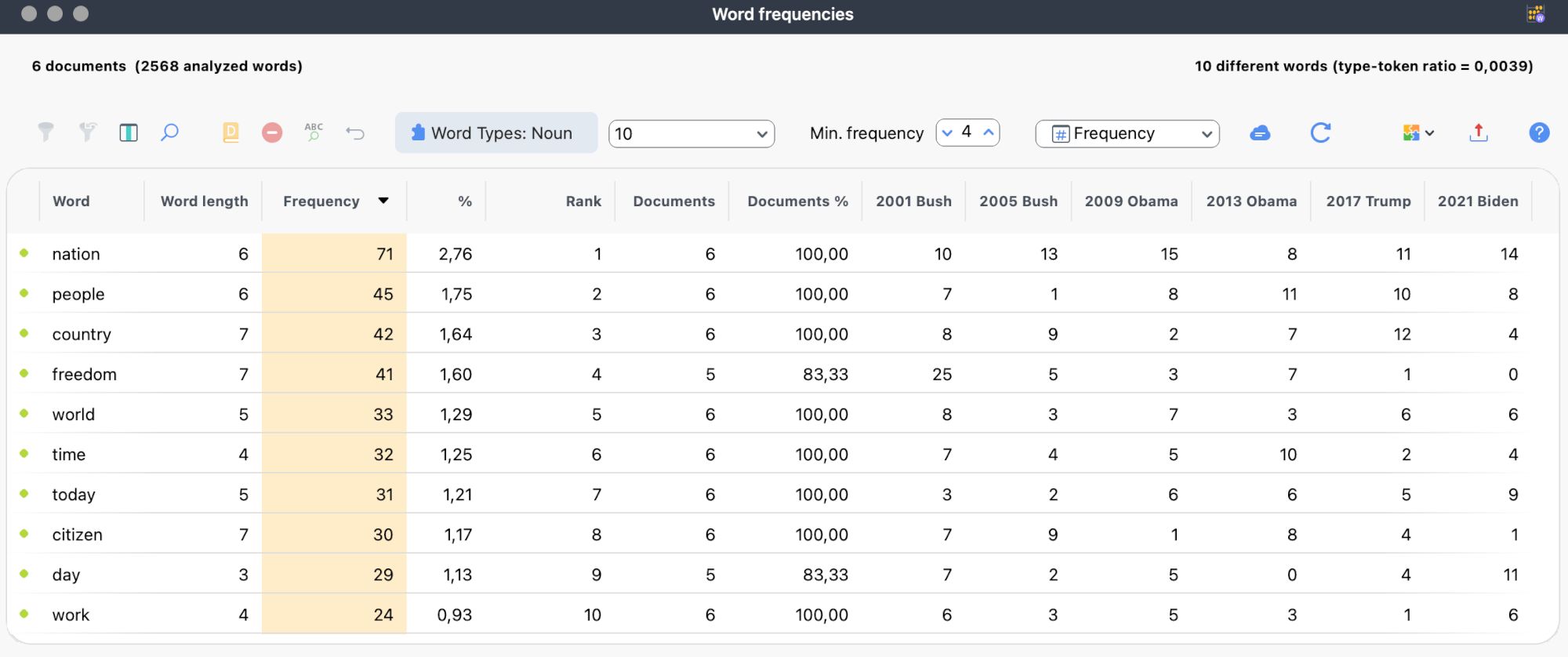

Frequency patterns can inform your coding decisions. A frequently used word might deserve its own code, especially if it aligns with your research questions. Conversely, a rare but theoretically important term could signal a need for more targeted searching or reading. You can even create document sets from the frequency table to examine where key terms appear across your data, helping you identify segments that merit closer analysis. - Leverage Word Type Filtering

MAXQDA allows you to filter the frequency table by part of speech, for example, limiting results to nouns, adjectives, or verbs. This can be especially useful when you’re looking for specific kinds of language. If you’re studying emotional tone, you might focus on adjectives. If you’re tracking action or agency, verbs might matter more. By narrowing the scope, you reduce noise and tailor the output to fit your analytical goals. The “Word Types” options window lets you choose both the text language and the part of speech you want to include in the analysis. - Use Table Columns to Spot Patterns

MAXQDA’s results table includes more than just frequency. Columns like word length, percentage of total words, rank, and “Documents %” (how many of your analyzed documents include the word) can provide additional clues. You can also switch the metric shown in the table cells to display rank, number of documents, or percentage of documents instead of frequency. This is especially helpful when comparing across document sets or speaker groups. For example, a term that ranks high in one group but appears only briefly in another might highlight a meaningful contrast. Not all options are available in every analysis view, but where applicable, this feature adds another dimension to your interpretation.

An iterative process

Word frequency analysis isn’t just a one-time numbers game. It can guide your entire workflow. From spotting key terms early on to refining your codes and presenting polished visuals, each step adds interpretive depth.

Zooming In: Seeing the Numbers in Action

To illustrate, let’s bring it all together with an example results table.

The table above displays the top 10 nouns across six U.S. presidential inaugural addresses (2001–2021), with results differentiated by document. This configuration sharpens the focus on concept-rich language while allowing comparisons across individual speakers.

Analytically, this setup balances breadth (frequency across the dataset) with specificity (variation by document). Tracking nouns captures core themes and symbolic vocabulary. If your focus were on agency, modality, or evaluative stance, you might instead filter for verbs or adjectives since each word type can offer a distinct lens on the discourse.

A careful read surfaces several useful patterns:

- Core terms anchor the genre.

The word “nation” appears in all six speeches and ranks highest overall, a reminder that inaugural addresses are rituals of national identity. Its consistent use likely reflects a foundational vocabulary of unity and belonging. You might not need to code “nation,” but its presence sets the discursive baseline. - Some words travel through time. Others stay put.

The terms “people,” “country,” and “world” appear across all documents, suggesting a consistent concern with collective actors and global positioning. In contrast, “freedom” spikes in Bush’s 2001 address (25 mentions) and vanishes by Biden’s. These shifts invite contextual reading: Is the decline a function of political ideology, historical moment, or rhetorical strategy? - Outliers matter.

The word “citizen” shows pronounced variation: it appears nine times in Bush’s 2005 speech but only once in Biden’s 2021 one. Such skews can point to localized themes, such as a focus on civic duty or a particular framing of the state’s relationship with the public. Click through those segments and read them closely. Outliers often carry ideological weight. - Not all frequent words are analytically helpful.

Words like “today” and “day” are common but likely mostly ceremonial; they mark the occasion rather than contribute to the speech’s thematic core. Use frequency not as a proxy for importance but as a guide: some words are scaffolding, others are signals. - Document % reveals breadth of usage.

The “Documents %” column indicates the extent to which a term is distributed across documents. “Nation,” “people,” and “country” are used in 100% of speeches, but “freedom” and “day” only appear in five of six. That’s a small difference, but it might mark a shift in tone or thematic focus, especially in a small dataset. Look here when you want to distinguish shared vocabulary from era- or speaker-specific language. - Use the counts as starting points—not conclusions.

Once a word catches your eye, either because it’s frequent, missing, or oddly placed, follow up with tools like Keyword-in-Context or

Keyword-in-Context or  Word Explorer. These let you see how a term is used sentence by sentence or in relation to others. Frequency maps the forest; interpretation begins when you start walking in it. For a closer look at MAXQDA’s Word Explorer, check out our blog post on favorite Word Explorer features.

Word Explorer. These let you see how a term is used sentence by sentence or in relation to others. Frequency maps the forest; interpretation begins when you start walking in it. For a closer look at MAXQDA’s Word Explorer, check out our blog post on favorite Word Explorer features.

This kind of table is valuable because it compresses a great deal of discursive structure into a legible form, combining macro-level pattern recognition with the potential for close reading, which is essential for effective mixed-methods textual analysis.

Remember:

Frequency tables point you toward phenomena that may require further investigation. They do not tell you what those phenomena mean in context.

4. Quick Actions in the Results Table

- Right-click on any word in the results table to:

- Add it to a stop word list or dictionary

- Activate the documents it appears in

- Create a document set based on search hits

- Open the word in

Word Explorer for deeper context.

Word Explorer for deeper context.

- Drag and drop to merge similar terms Combine conceptually related words by dragging one term onto another. The merged row is marked with a

sum icon. Hover over the icon to see a tooltip listing all terms included in that row. To undo, click the

sum icon. Hover over the icon to see a tooltip listing all terms included in that row. To undo, click the  undo arrow in the table’s toolbar.

undo arrow in the table’s toolbar. - Click the

Word Cloud icon to quickly visualize dominant terms, which is especially useful for presentations or spotting key language patterns at a glance. Read more about MAXQDA’s Word Cloud feature by following this link.

Word Cloud icon to quickly visualize dominant terms, which is especially useful for presentations or spotting key language patterns at a glance. Read more about MAXQDA’s Word Cloud feature by following this link. - Double-click a word to open a detailed “Search Results” window to see every instance in context. From there, you can:

- Autocode search hits, or

- save the number of hits per document as a variable

5. Use Cases Across Different Data Types

To illustrate the flexibility of MAXQDA’s Word Frequencies tool, let’s walk through several real-world scenarios.

Recruitment Trends in Job Advertisements

Explore how lexical choices reflect organizational culture in hiring discourse.

Suppose you are studying how employers describe remote work in tech job ads. You import recent postings into MAXQDA, activate them, and run a frequency analysis. Terms like “remote,” “hybrid,” and “team” dominate. Differentiation by document group (e.g., startups vs. established firms) reveals that smaller companies emphasize “flexibility” and “innovation,” while larger organizations focus on “benefits” and “career development.”

This lexical contrast may reflect distinct organizational cultures and recruitment strategies: startups foreground autonomy and entrepreneurial identity, whereas corporations stress institutional stability. Here, word frequency analysis highlight how companies frame their identity and values in hiring language., inviting deeper inquiry into how work conditions are rhetorically constructed to attract different labor segments. It also prompts reflection on the alignment (or misalignment) between advertised values and actual workplace practices.

Discovering Participant Vocabulary

See how word frequencies reveal generational differences in caregiving narratives.

In a study of caregiving, you might run a frequency analysis on segments coded under “challenges.” Words like “time,” “support,” “stress,” and “family” appear most often. Differentiating by speaker shows that younger participants mention “time” and “workload” more, while older participants talk about “health” and “support.”

These patterns suggest generational differences in how caregiving responsibilities are experienced and framed. For younger respondents, the tension appears to lie between paid labor and informal care, whereas for older participants, the focus shifts toward health deterioration and emotional networks. These patterns can indicate age-related differences or role tensions, which are areas worth coding further or considering in your theoretical framework.

Social Media Activism

Trace how activist discourse constructs urgency and justice through repeated terms.

When analyzing social media comments from an environmental campaign, you can exclude hyperlinks and user handles via the “Ignore” options and apply a Stop Word List to remove platform‑specific words. Counts reveal that “climate,” “justice,” “youth,” and “future” are recurring themes.

These recurring word patterns may suggest a discourse framed by intergenerational urgency and moral appeal. The prominence of “justice” and “youth” in particular aligns with climate justice rhetoric that centers inequality, responsibility, and temporal stakes. Rather than treating these words as standalone findings, their frequency can direct attention to how affect and temporality are mobilized in activist communication, opening a path toward discourse or frame analysis.

Policy Documents and Legal Texts

Compare policy paradigms across national contexts using lexical frequency.

For a comparative policy analysis, you can group environmental statutes by country and differentiate the frequency count by group. The table might show that one country uses terms like “sustainable” and “renewable,” another emphasizes “compliance” and “obligation,” while a third focuses on “innovation” and “incentives.”

These word choices may reflect different policy logics, like a focus on sustainability, regulation, or market incentives. In this case, frequency analysis offers an early way to spot differences in how policies are framed. It can also inform a targeted coding scheme or guide selection for in-depth comparative discourse analysis.

6. Advanced: Dictionaries and Go Word Lists

As we briefly mentioned earlier, beyond a simple count, you can restrict the analysis to specific words listed in a Dictionary or a Go Word list. Both options support targeted explorations without requiring you to wade through every word. This shifts the focus from emergent patterns to theory-driven queries, supporting deductive or abductive analysis strategies.

Dictionaries

Dictionaries

When you select MAXDictio › ![]() Word Frequencies › Word Frequencies (Only Words From Dictionary), MAXQDA filters the count to include only words from your currently active user-defined dictionary. This is especially helpful when you’re working with predefined categories of interest, such as “climate-related terms,” “skill keywords,” or “political rhetoric,” and want to track their frequency across your dataset without noise from unrelated words.

Word Frequencies › Word Frequencies (Only Words From Dictionary), MAXQDA filters the count to include only words from your currently active user-defined dictionary. This is especially helpful when you’re working with predefined categories of interest, such as “climate-related terms,” “skill keywords,” or “political rhetoric,” and want to track their frequency across your dataset without noise from unrelated words.

For qualitative researchers, dictionaries serve not merely as filters but as operationalized conceptual frameworks. A carefully constructed dictionary can reflect your theoretical orientation. For example, a discourse analysis project on nationalism might include categories like “territory,” “people,” and “threat,” each with its own lexical variants. By restricting frequency counts to terms that align with your analytical lens, you can more precisely map discursive patterns, trace ideologies, or test and refine your theoretical ideas..

Dictionaries in MAXQDA are structured collections of search items, grouped into categories that you define. They can be simple keyword lists or more complex hierarchies with subcategories and tailored matching rules, such as case sensitivity or whole-word matching. You can reuse dictionaries across projects, import them from Excel or TXT files, and build them interactively as you explore your data.

For a detailed walkthrough on creating, organizing, importing, and managing dictionaries, including how to use them across projects and link them to your code system, see the MAXQDA user manual on Managing Dictionaries.

Go Word Lists

Go Word Lists

When you select MAXDictio › ![]() Word Frequencies › Word Frequencies (Only Go Words), MAXQDA limits the frequency count to words from your currently active Go Word List. This is conceptually the reverse of a stop word list: instead of excluding unwanted terms, a Go Word List includes only the words you want to analyze.

Word Frequencies › Word Frequencies (Only Go Words), MAXQDA limits the frequency count to words from your currently active Go Word List. This is conceptually the reverse of a stop word list: instead of excluding unwanted terms, a Go Word List includes only the words you want to analyze.

For qualitative researchers, Go Word Lists offer a way to bring analytical focus into frequency analysis. By specifying in advance which words reflect your research interests, Go Word Lists help filter out lexical noise and surface patterns that speak directly to your conceptual framework. Whether you’re interested in language around “justice,” “risk,” or “governance,” narrowing your frequency count to a defined vocabulary helps you trace those themes more precisely across your data.

Go Word Lists are especially useful when you’re working with large or noisy corpora, conducting cross-case comparisons, or applying a deductive coding strategy. In longitudinal or multi-site research, a consistent Go Word List can also help ensure that different datasets are analyzed through the same lexical lens.

To create or edit a Go Word List, go to MAXDictio › Go Word List. The editor functions similarly to the stop word list window, letting you add, remove, import, or manage your lists across projects.

For full documentation on how to manage Stop and Go Word Lists, see the MAXQDA user manual.

7. Reading Beyond the Numbers: Caveats and Reflexive Practices

Word frequency analysis can be a powerful tool but when used carelessly, it risks obscuring meaning rather than revealing it. Below, you’ll find key reasons why frequency statistics can mislead, along with tips on how to avoid those pitfalls in MAXQDA:

Why Counts Can Mislead

- Mistake in Quantification: Elevating numeric prominence to analytical significance risks treating frequency as a proxy for importance rather than a heuristic for further interpretation.

- Polysemy and Practical Contexts: The same word (“stress”) may denote physiological strain, grammatical emphasis, or even a pun. Frequency conflates these pragmatic contexts, potentially inflating trivial homonyms while masking distinct meanings.

- Structural Silences: Marginalized people often appear in the data through omissions, euphemism, or absence. Their concerns can register aslow frequency precisely because power relations suppress explicit articulation.

- Genre Conventions: Highly ritualized genres embed formulaic wording that skews counts toward stylistic scaffolding rather than substantive themes.

- Vocabulary Variance: Languages with rich inflection or productive compounding disperse semantic load over many surface forms, depressing individual frequencies and complicating cross-linguistic comparison.

Practical Safeguards

- Review Context Iteratively: After spotting a salient term, launch MAXQDA’s

Keyword-in-Context or

Keyword-in-Context or  Word Explorer. Read at least five surrounding sentences before coding or interpreting.

Word Explorer. Read at least five surrounding sentences before coding or interpreting. - Document Decisions Reflexively: For every stop word, lemmatization, or go word decision, add a note in your project memo explaining the theoretical rationale (e.g., “merged ‘regulation/regulatory’ to track juridical framing”). This helps document your reasoning and creates a transparent trail of decisions.

- Compare Groups: Run the same analysis on different sets of texts (like “junior staff” vs. “executives”). If a word shows up frequently in one group but not the other, that contrast can reveal differences in perspective or power dynamics.

- Check for Missed Patterns: Lower the minimum-character threshold and disable stop words for one test run. If new themes emerge, reconsider earlier filtering; if not, your original settings are likely to have preserved the analytical signal.

- Track Rare but Theoretically Relevant Terms: Create a code for theoretically significant but infrequent terms. Track their distribution via MAXQDA’s variables or code statistics to stay open to less common but important patterns.

8. In a Nutshell: Seeing the Forest and the Trees

MAXQDA’s Word Frequencies helps you map the forest so you do not get lost in the trees. It shows you where the canopy is dense, where paths diverge, and where a clearing might be worth a closer look. The map is not the hike, so bring it with you, then read in context, memo your decisions, and keep adjusting the route.

Word frequency analysis isn’t about following the biggest numbers; it’s about treating them as breadcrumbs to follow. MAXQDA’s Word Frequencies tool lets you zero in on the language patterns that matter, whether it’s spotting recurring terms, highlighting differences between groups, or finding passages that deserve a closer read.

The key is to define your scope carefully, refine the counts with tools like Stop and Go Lists or Dictionaries, and always return to the surrounding context before drawing conclusions. High-frequency words can guide your attention, but meaning only emerges when you compare across groups, reflect on what’s there (and what’s absent), and keep a memo trail of the decisions that shaped your results.

The key is to treat counts as signposts, not conclusions. With careful coding and context, a frequency table becomes a powerful entry point into your data.

Try this now: Open MAXQDA and run Word Frequencies on a small subset of your data, turn on differentiation by group, pick three terms that matter, and open each in Keyword-in-Context. Write a 5-line memo on what changed in your understanding. If the memo is empty, rerun with different settings and try again.

Über den Autoren

Xan (he/him) recently completed a master’s degree in sociology. He now works at VERBI Software, where he spends his time testing AI prototypes, writing about MAXQDA, and occasionally surviving thesis flashbacks by turning them into blog posts.