Guest post by Haitao Yu.

Despite significant social and economic progress during the past two centuries, economic development – ironically – has put some communities’ livelihoods in peril through globalization. As the 21st century unfolds, sustainable development, the development that meets the current generation’s needs without compromising the interest of future generations, has become both a timely and immensely imperative issue regarding ecological limits. Our understanding of sustainable development in Indigenous communities, however, is particularly under-examined as the local worldviews often collide with the dominant Western way of thinking.

It is important to study sustainable development in Indigenous communities because they are often the most in need of it and most vulnerable to economic exploitation – and the least able to make their sustainable development aspirations heard. In my research, I seek to address the question of how organizations can contribute to sustainable development in Indigenous communities through place-based organizing.

Ethnographic Work in the Peruvian Andes

In 2017, I conducted a three-month ethnographic study on the Tibetan Plateau of a social enterprise called Norlha Textiles, which utilizes yak wool to create high-end textiles, thus offering sustainable livelihood for the members of a Tibetan nomadic village. This experience sharpened my ability to conduct culturally appropriate, community-based, and collaborative research in an Indigenous setting.

During this study, I also came to learn about some European luxury textile companies’ work on alpaca fiber in the Peruvian Andes. I expected that there might be something similar happening in the Andes, where organizations use local resources to develop the economy while contributing to cultural preservation. This discovery became the basis for my current fieldwork project.

The small buildings that are located in the “desert” bordering the volcanoes are where the immigrants live in the city of Arequipa

Data Access Strategy

Following a phase of ‘desk research’, I realized that there is an even bigger alpaca fiber industry in the Peruvian Andes than on the Tibetan Plateau. One of the leading companies I found consistently mentions the connection between their work and Peru’s cultural heritage and ecological well-being in their media communications. They even established an independent organization called Pacomarca (sustainable alpaca network) to support the sustainable use of alpaca fiber. This information strengthened my belief that there is more to be researched in this region.

Through a contact in Peru, I was introduced to a professor at the National Agrarian University in Lima, who is working on alpaca gene refinement. The professor kindly introduced me to the International Association of Alpacas in Arequipa, which mediated my research with organizations working on alpaca fibers in the Andes, and that is how I came to be where I am today.

Local Context

What is similar in the Peruvian Andes to what has been happening on the Tibetan Plateau is that there are several issues surrounding migration. At the end of the last century, Peru experienced a huge wave of migration from rural areas into big cities. One specific cause of the migration wave was the formation of terrorist groups in rural Indian communities. In 1980, Sendero Luminoso, a terrorist group founded in the 70s on the basis of Marxist, Leninist, and Maoist theories, started an armed fight within the country. Although many of the Sendero cadres were of rural and Indian origin, the Sendero Luminoso was not an Indian movement and didn’t respect the Indian communities or their authorities. Some of the people of the Andean communities that weren’t willing to follow the Sendero Luminoso were massacred as a warning to others.

Today, many people from rural communities still come to Lima in search of employment or educational opportunities and often end up living in slums along the mountainsides where they don’t need to pay for the land. These mountainside neighborhoods are considered very dangerous areas for both locals and non-locals.

The Rimac District, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Lima

(some slums on the mountain)

Data Collection Strategies: Grounded Theory-Based Ethnography

Given that my research intends to answer a “how” question, a focus on the process of theory-development is particularly fruitful in providing fundamental theoretical and empirical insights into the issues of sustainability and sustainable development. I am therefore using grounded theory data analysis methodology as my methodological framework to analyze my ethnographic data.

Grounded theory emphasizes the development of theories “grounded” in the data itself, on the basis of an epistemology that sees the researcher as part of the researched empirical world. Thus, the majority of my data collection is conducted using an ethnographic and bottom-up approach such that the enriched empirical data I collect in the field will be directly included in what would otherwise be an abstract theory.

Archival Data

As I mentioned above, before I began the ethnographic fieldwork portion of my research project, I conducted extensive ‘desk research’ on the alpaca industry, gathering information from publicly available sources, such as books and official business websites. These public documents served as kind of base from which I customized the design of my in-depth interview questionnaire.

Because I designed the interview questions for the target participants ahead of time, I was able to go into the field with a more sensitive awareness of the local and industrial context while I was conducting my interviews and observations.

In-depth Interviews

During my fieldwork in Peru, 13 formal interviews were conducted, lasting 30-120 minutes each (averaging 40 minutes). I scheduled interviews with entrepreneurs, top management executives, academics in the Arequipa region, and young people from the Puno region. The interviews were semi-structured to allow for follow-up questions that emerged during the interview process.

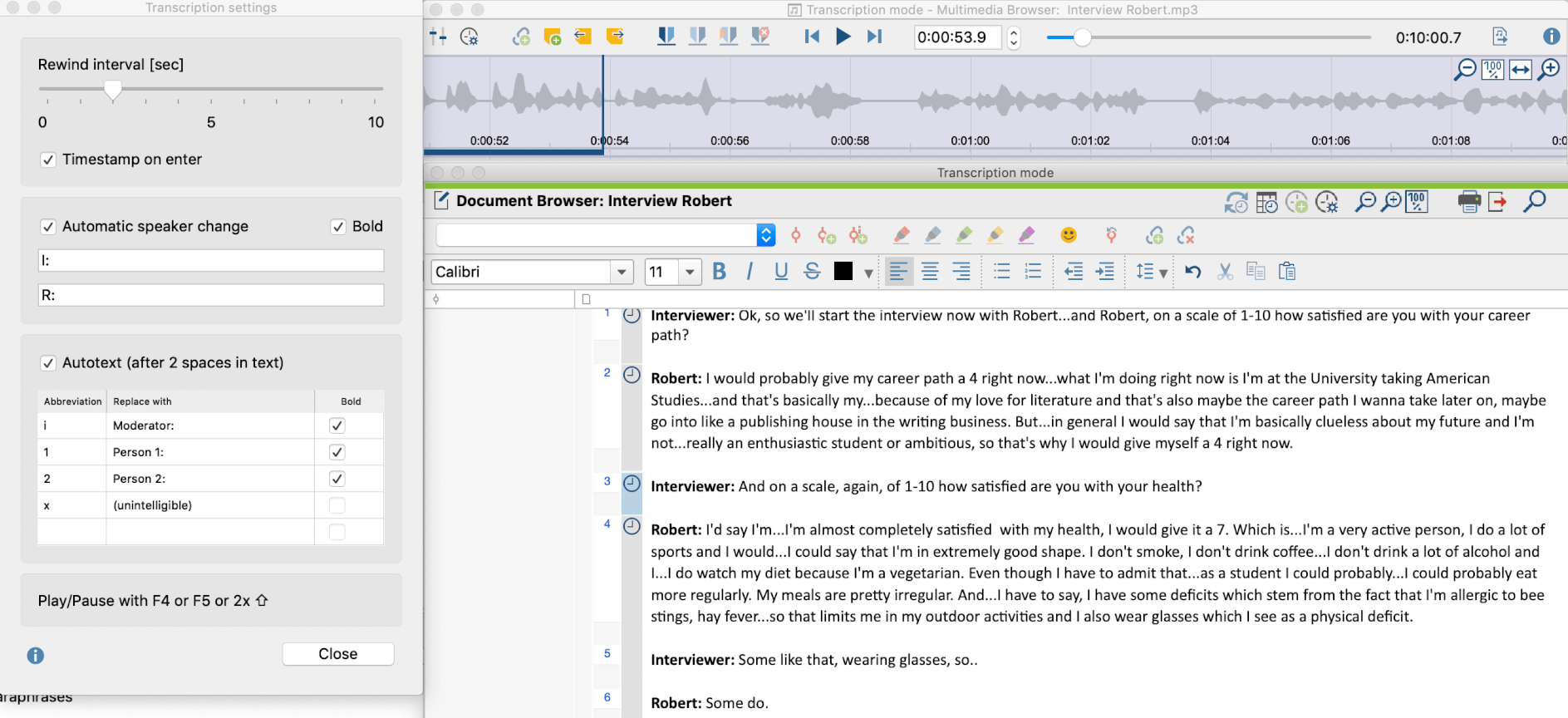

All the formal interviews were recorded and I transcribed the audio files using MAXQDA’s Transcription Mode. MAXQDA’s transcription tool has been extremely useful for my research project because I could link the transcripts with participants’ voices, allowing me to analyze non-verbal clues that arose during my interviews.

Transcribing audio files using MAXQDA

(picture retrieved from VERBI Software due to data confidentiality concerns)

Data Analysis Strategies: Grounded Theory Analysis with MAXQDA

In grounded theory, qualitative data analysis starts parallel to the collection of data in an iterative manner, so I began analyzing the data while I was conducting my ethnographic fieldwork. For example, before conducting follow-up interviews with key participants, I listened to the previously recorded interview a few times and transcribed them so I could write up more insightful comments and search out any puzzles as they merged.

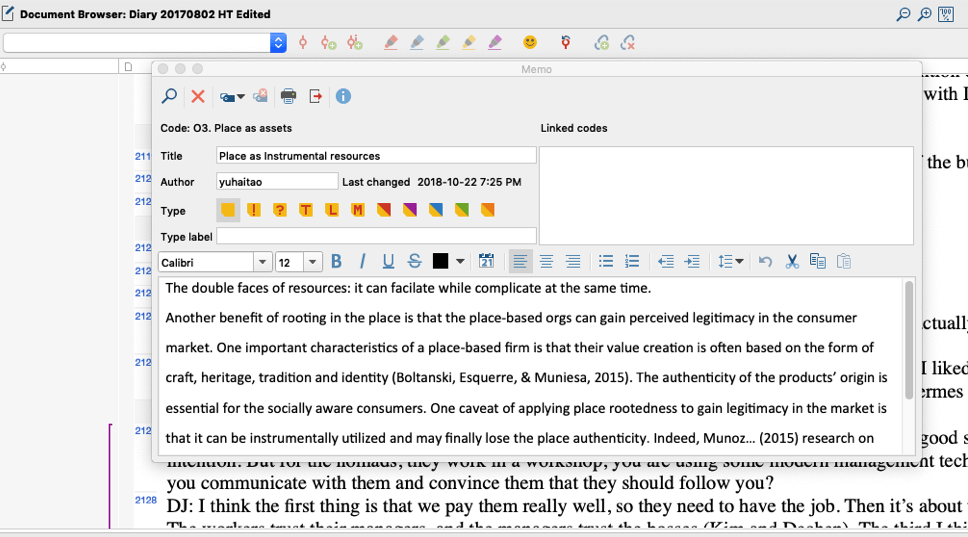

Writing memos in MAXQDA

Creating Codes and Memos

MAXQDA was very helpful when it came time to code my data. First, MAXQDA’s “Code System” window allows you to organize many open codes from different data sources (interview transcripts, journal notes, images, videos, etc.) in a visual way. Second, the MAXQDA’s memo functions allow you to track emerging ideas, and “a-ha” moments found in codes and data. I wrote up extensive document memos about my emerging ideas by using MAXQDA’s memo functions.

The coding process in my research project was guided by three specific questions:

- What is the place?

- What features of the place enabled or disenabled the pattern of organizational response?

- What emerging process organization and organizational members take in their place?

My coding process was therefore indeed iterative, and so far I have completed three rounds of coding. In my first round of coding, I open-coded the archive data and the interview transcripts by fracturing and analyzing the data from informants line by line. One puzzle I had to solve was what qualified as a line? Glaser (1978) suggests that a sentence is a line.

However, for interviews, it is difficult to identify a sentence that describes one idea. My operationalization was to try to define a section that describes one thing as a line, be it several words, one sentence, or several sentences. The open coding process generated about 100 first-order codes. The advantage of conducting line-by-line coding is that the process allows the data to speak for the informants and avoids the tendency to assign general themes by reading and summarizing the graph in an abstract manner.

The disadvantage of conducting this line-by-line style of coding is that I generated too many open codes. Two main problems arose: First, I lost the focus of the analytical theme. Second, it became difficult for me to continue to code the data because I couldn’t even remember what codes I had already created and if some codes describe the same theme. I initially thought that MAXQDA would automatically figure out how to organize a large number of open codes, but while software supports your analysis goals with all the tools you need, you still need to organize the code system yourself according to your methodological framework and research goals.

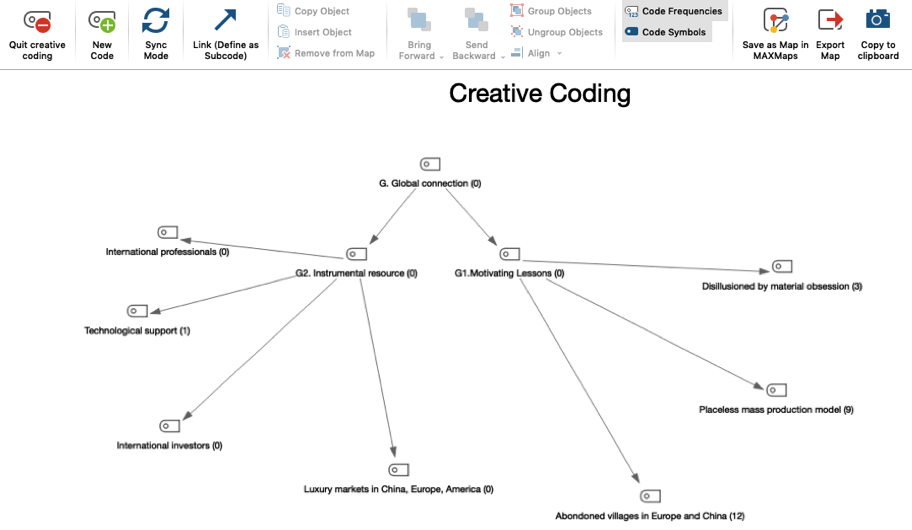

Organizing Open Codes

Thus, the next step was to organize these temporary open codes. This step was conducted using MAXQDA’s Creative Coding function, which allowed me to cluster codes on the basis of similarities and differences. I also conducted axial coding, the process by which categories are related to their subcategories. I wrote memos to describe the casual conditions, intervening conditions, action strategies, and consequences of conceptual categories. Using these paradigms, I chose to cluster codes that describe the same phenomenon under 18 conceptual categories. After that, I tried to focus my coding work on the remaining documents, including my field notes and media accounts, by using the newly organized first-order codes.

There were still too many first-order codes and conceptual categories even after all of this analysis work, so I then decided to select the most salient codes among the current 100 codes and aggregate the conceptual categories before conducting focused coding. I checked:

- if first-order codes that describe the similar concepts could be merged,

- if the categories could be subsumed under a broader theme, or

- if some categories could be collapsed and combined into more general themes as part of a place theory.

Use MAXQDA’s Creative Coding tool to reorganize codes

Next Stages in the Research Process

Researchers suggest that Indigenous communities in North America have well-developed knowledge on managing the places where they live and have deep spiritual, cultural, and ecological connections with these places. I am currently planning my next fieldwork phase at an Indigenous community in southwest Ontario, where there are more than 70 endangered species of animals. In 2018, I spent 10 months building up a relationship with the community and exploring how my research and participation could generate concrete benefits for the community.

Methodologically, I’m exploring the use of drones to capture the ecological system in the community where organizations are embedded, which is especially valuable to sustainability research since conventional work suffers from treating organizations as discrete entities from the ecological system. I’m looking forward to using MAXQDA’s video analysis tools to analyze the drone data!

Drone images showing ecologically embedded work and the organization embedded in its ecological system

Editor’s Note

Haitao Yu is a PhD candidate for General Management in Sustainability at the Ivey Business School of Western University, Canada. For his research project titled “Place-based Organizing in Indigenous Communities”, he has already completed fieldwork in Tibet, is currently based in Peru, and will return to Canada to gather data at his third field site in southern Ontario. Make sure to keep an eye out for updates here in the MAXQDA Research Blog from Haitao as he continues his research journey with MAXQDA!